The announcement that the State of Louisiana had purchased land for a resettlement project spearheaded by the Isle de Jean Charles Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe (IDJC) reached the Tribe’s executive secretary, Chantel Comardelle, via an emailed press release. The news hit her like a slap in the face.

Despite being involved with the project from the beginning, she received no direct notification. She assumed the State hadn’t told IDJC Tribe Chief Albert Naquin directly either and relayed the news to him. Both took offense for not being notified directly of the purchase’s completion, though they were aware of, and had concerns about, the State’s plan to buy the property.

The way Comardelle received the news is indicative of why the IDJC Tribe recently told the federal government, which is funding the move of America’s so-called first “climate change refugees,” that the tribal community is turning down the $48 million federal offer and withdrawing from the State’s Isle de Jean Charles resettlement project.

“The State has no respect for our culture,” Comardelle said during a phone call shortly after the January 9 announcement celebrating the $11.7 million land deal.

Disappearing Island, Disappearing Community

The Isle de Jean Charles is a dwindling strip of land in Louisiana’s wetlands about 80 miles southwest of New Orleans. Since 1955, it has lost 98 percent of its area due to a combination of levee construction, coastal erosion, sinking land, rising seas, and damage from hurricanes worsened by climate change. Of the 22,400-acre island that stood at that time, only a 320-acre strip remains today.

The island is only accessible by one road, which is at times under water. If the road is washed away, as it has been in the past, the state likely won’t rebuild it because most projections show the island will be uninhabitable in the near future.

The IDJC Tribe members are descendants of Biloxi, Chitimacha, and Choctaw Indians, who ended up on the Isle de Jean Charles while escaping the harsh and involuntary relocations of Southeastern tribes under the Indian Removal Act of the 1830s. They created a self-sustaining community, but began dispersing as life on the island became more perilous with each passing hurricane. The 600-member tribe had been planning to relocate for two decades.

Tribal members were dubbed the nation’s first “climate change refugees” in 2016, after the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) awarded the State a grant, in large part on behalf of the Tribe, which would help them relocate. The funds would come from the agency’s $1 billion National Disaster Resilience Competition, aimed at helping communities adapt to climate change by building resilient infrastructure and housing.

HUD allotted $92 million to Louisiana for disaster resilience projects, of which $48 million was earmarked for the relocation of the IDJC Tribe.

By Chief Naquin’s count, there are, at most, 34 families who still live on the island. The exact number is hard to pin down because the population is in flux. Most of the residents are members of the IDJC Tribe, a fact the state doesn’t dispute.

Tribe Says “No Thanks” to Government Plan

Chief Naquin did not think that the State’s land purchase was anything to celebrate, but he told me, during a call after the news broke, that he wants people to know his tribe’s stance on the resettlement project: In an October 29, 2018 letter to Stan Gimont, the director of the Office of Block Grant Assistance at HUD, the IDJC Tribal Council recommended that its grant funds be returned to the National Disaster Resilience Competition Grant committee.

The letter explained that changes the State made to the IDJC Tribe’s original plan didn’t reflect the goals and objectives the Tribe outlined in its application for the grant in the first place. For example, the island residents who agreed to relocate, now do so at the risk of losing ownership of their existing homes on the Isle de Jean Charles — something few are willing to risk.

“The last thing anyone wants to do is sign away the legacy from their ancestors who worked so hard to keep it,” Chief Naquin wrote in the letter to HUD. “Our Tribe feels this is dishonoring of everything our ancestors did to ensure we survived the Indian Removal Act 1830, Indian Relocation Act of 1956, Jim Crow Laws, and other discriminatory acts.”

Additionally, Chief Naquin hopes that the IDJC Tribe can shake the myth that it is rich, which spread after its award of the HUD grant. The Tribe hasn’t directly received a penny of the grant, he told me, and is trying to find new funding to help realize its original resettlement plan.

That is a difficult undertaking made more challenging because potential grant-makers reportedly think the Tribe is flush with cash. In addition, Chief Naquin only now chose to make public the Tribe’s withdrawal from the grant because the Tribe has no reason to think the government agencies involved will make things right after purchasing the land without addressing its previously voiced concerns.

As far as Chief Naquin is concerned, “The government should take the money back and leave the Tribe alone.”

Before notifying HUD of the Tribe’s withdrawal, Chief Naquin sent a strongly worded letter to the Louisiana Office of Community Development (OCD) on September 25, 2018, expressing grave reservations about the resettlement project. Neither the OCD nor HUD replied to his letters before the state purchased 515 acres of farmland in the Schriever area of Terrebonne Parish to resettle the Isle de Jean Charles community.

Neither Chief Naquin nor Comardelle were surprised that the state moved ahead without resolving the Tribe’s concerns. “The government breaking deals with tribes is nothing new,” Chief Naquin said.

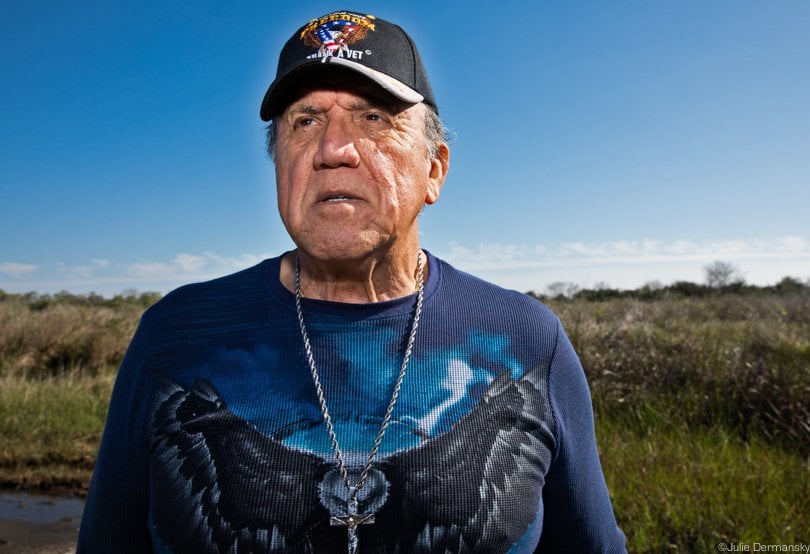

I met with Chief Naquin on January 4 at his home in Pointe-aux-Chenes, a small town en route to Isle de Jean Charles. He moved off the island in 1975, after Hurricane Carmen flooded his home. From there we headed to the island, where Chief Naquin, who is also an acolyte for a local Catholic church, made wellness checks and administered communion to some of the island’s elders who are unable to make it to mass.

Residents I met on the trip included Denecia Naquin Billiot, Comardelle’s grandmother, who told me that she doubted the resettlement project would happen.

I spoke with other tribal members at their Christmas gathering, held December 23 at the Isle de Jean Charles fire station. They also had no faith that the State’s planned community would work out.

State of Louisiana: Community Relocation Going Ahead

A couple of hours after the State announced the land deal, I spoke with OCD Executive Director Patrick Forbes on the phone. He told me that while he welcomes the IDJC Tribe’s input, the resettlement project is about the entire island community.

He learned shortly after the grant was awarded in 2016 that there were stakeholders on the island other than IDJC Tribe members. These included members of the United Houma Nation and residents who are not affiliated with any tribe. As a result, the OCD changed the original project in a way that dealt with the entire Isle de Jean Charles community, not just the IDJC Tribe.

When I asked if the project will go forward as planned, Forbes said it would, and while he still hopes Chief Naquin will participate, he pointed out that the chief had moved off the island years ago. Forbes’ first concern is for those who are still island residents and others who relocated after Hurricane Isaac flooded the island in 2012. They are the first who will be in a position to move to the new community, he said.

“Let’s be clear,” Forbes said, “Chief Naquin sent a letter asking that this project be canceled, but I’m not sure how that makes him a stakeholder in this process now. I’m not sure how I characterize his participation in our process as being in good faith.”

After island residents are resettled, others with ties to the island, like Chief Naquin, will be welcome to build homes in the new community, too.

Forbes said that he has every intention of continuing to communicate with Chief Naquin. “We are going to continue to engage with him just as we continue to engage with the United Houma Nation,” he said, “because they can be excellent conduits to a huge audience that we need to reach — folks who can come back and reconstitute this community to something like it was before the island started getting ravaged by sea-level rise and failing coastal land.”

When I asked how many United Houma Nation members are still island residents and how many lived on the island before Hurricane Isaac, Forbes couldn’t give me a number.

Chief Naquin and Comardelle maintain that only a handful of Houma Indians have ties to the island. “If the Houma want a grant, they should apply for their own grant,” Naquin said.

The United Houma Nation and the IDJC Tribe have a longstanding rivalry, according to a March 2018 story in HuffPost. Chief Naquin is disappointed that the State let the Houma Nation interfere with his tribe’s resettlement project, which was over a decade in the making.

“You can’t separate the Tribe from the island or the island from the Tribe,” Comardelle explained when we spoke on January 9. She only knows of three people identifying with the United Houma Nation and one white man who bought a house on the island in 2008, who meet the state’s requirements to be part of the resettlement project’s first wave. She said that the IDJCTribe never said the island’s residents who are not part of the tribe couldn’t be part of the project.

However, the resettlement project was supposed to be guided by the IDJC Tribe, not the State.

“Albert [Chief Naquin] speaks for all of his constituents in the Tribe — he is not one stakeholder,” Comardelle said. “Dismissing the chief’s importance goes against the United Nations Declaration of Indigenous Rights.” For the State to buy the land before resolving the Tribe’s concerns shows that the State is “not acknowledging our right of self-determination and self-sovereignty,” Comardelle asserted.

Comardelle was referring to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Resolution, adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2007, and establishing international norms and standards for treatment of Indigenous peoples. The declaration was adopted by a majority of UN members, including the United States.

Climate-Vulnerable Tribes on the Watch

Other Native American tribes in coastal areas at risk from the impacts of climate change have been following this project closely. It is the first government-funded project meant to resettle an entire community due to climate change.

Betty Osceola, a member of the Miccosukee Tribe and Panther Clan based in the Florida Everglades, is paying careful attention to what is happening in Louisiana. Her tribe is also threatened by the impacts of climate change.

“A tribal chief is like the President of the United States. For his people to ignore a tribal chief is the equivalent of ignoring the President of the United States,” Osceola said on a call after Louisiana announced the land purchase. “That is the level of disrespect Native Americans have grown accustomed to when dealing with the state and federal government.”

“The State is ignoring indigenous sovereignty if it doesn’t work directly with the IDJC’s chief,” she said, noting that “nothing has change since the cowboy and Indian days. Tribes are meant to be managed, not worked with like equals.”

A Meeting Gone Wrong

The IDJC Tribe’s withdrawal from the State’s project came after a contentious meeting with representatives of the OCD that took place on October 8, 2018. State Representative Tanner Magee, whose district includes the island, attended the meeting.

The meeting was meant in part to foster better communications between Louisiana and the IDJC Tribe. The main topic discussed was the State’s recent provision requiring island residents who wanted to have a house provided by HUD in the new community accept a mortgage deal that leverages their homes on Isle de Jean Charles against their new homes.

The OCD representative explained that the homeowners would still be entitled to use their property on the island, but only for things like recreational use and upkeep. Anyone who accepts a new house would have to make that home their primary residence and would be forbidden to live on the island anymore.

Forbes explained that the OCD is still working to come up with a few options for those who want to participate in the project but object to a provisional mortgage. Whatever the solution the State comes up with, ultimately, it has to meet all the legal requirements for providing new housing outlined by HUD.

Will State Plan Leave Island Residents Without a Home?

State Rep. Magee described the project as problematic from the get-go.

“There’s a lot of deep-seated cultural issues layered on top of environmental issues that have led us to where we are,” he wrote in an email. “Unfortunately, the State was warned of the difficulty and chose to ignore it, thinking they could handle these issues. I think D.C./Baton Rouge types overconfidently thought they knew better, and didn’t listen to locals really. Without a real understanding of the issues it was facing, the State blundered its way through this.”

He added that he believes “the double-mortgage provision is against the nature of the project. As I understand it, the goal is to move an environmentally vulnerable group of people who lack enough means to move and, at the same time, maintain the group’s cultural identity as best as can be. I think this has morphed into the State trying to see how good of a development it believes it can construct under its own definitions of what it should look like.”

He added: “Currently, the project is heading towards building a community that a significant portion of the Isle de Jean Charles community doesn’t want to move to; a community that no one else in Terrebonne Parish will want to move to; and potentially leaves a portion of the Isle de Jean Charles community with no home at all.”

If the project is built, Magee expects that “in a few years, you’ll have a development of residents not from the island living in squalor, and the actual residents will be living elsewhere or still on the island.” Despite his negativity, he believes that things can be fixed.

Comardelle and Chief Naquin remain optimistic that the Tribe will find a solution; however, they doubt it will have anything to do with the government. They have worked too hard to ensure the continuing existence of the IDJC Tribe to give up now, they say, and have already met to start planning what comes next.

Correction: This story has been updated to clarify that the State directly received the grant, rather than the IDJC Tribe, which had a large part of it earmarked for their relocation.

Before Midnight: Last Chance to Have Your Gift Matched!

Before midnight tonight, all donations to Truthout will be matched dollar for dollar up to $15,000! Thanks to a generous supporter, your one-time gift today will be matched immediately. As well, your monthly donation will be matched for the whole first year, doubling your impact.

We have just a few hours left to raise $15,000 and receive the full match.

This matching gift comes at a critical time. As Trump attempts to silence dissenting voices and oppositional nonprofits, reader support is our best defense against the right-wing agenda.

Help Truthout confront Trump’s fascism in 2026, and have your donation matched now!