China Miéville’s fiction bursts with outlandish ideas: On almost every page readers will find ideas so potent and engrossing that other authors would make them the basis for an entire novel.

Whether it’s the floating pirate city of Armada in The Scar, the revolutionaries who occupy a train and turn a tool of capitalist expansion into a mobile community in Iron Council, or the way in which The City and The City highlights the absurdities of borders and nation-state jurisdiction, his books have always had a rich political seam and a particular engagement with the idea of place. These trends continue in the weird blending of ecology, language, biology and technology in Embassytown and the literal underground railroad of Railsea.

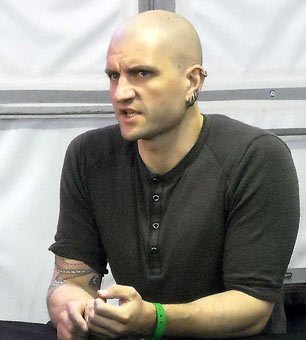

When it comes to our world, Miéville combines a radical vision with a clear-eyed insight into political, social and economic realities. A proud member of the UK’s Socialist Workers Party, the British author has always been forthright about his political thinking and activity. Now his country of origin (which happens to be mine too) is currently being dragged savagely to the right by the unholy alliance of the Conservative and Liberal Democratic parties.

The impact this has had on London, the city that looms large in several of his books (as an explicit setting or the influence for more alien geographies), is explored in his essay “London’s Overthrow,” a piece of work that is hard to categorize but undeniably evocative. The essay, best read in its original full-length form complete with haunting photos and imagery, takes the form of a psycho-geographical, exploratory wandering through a city recently burned by riots, supposedly being renewed for the 2012 Olympics, and occupied in protest against enforced “austerity.”

Even though Chicago failed in its bid to host the 2016 Games, parallels with London continue to abound: Both cities suffer from massive inequality made worse by allegedly media-savvy mayors who like to cloak their neoliberalism with tokens of social tolerance. Much like London’s Games, Chicago recently hosted a “global event” that promised prosperity but brought none, in the form of the NATO summit.

In June, Miéville addressed the Socialism 2012 conference in Chicago on the topic of “Guilty Pleasures: Art and Politics” (his insightful, witty talk can be heard here.) It is readily apparent that, even leaving his fiction aside, Miéville is worth listening to and reading.

Here he speaks with the Occupied Chicago Tribune about the power and limitations of occupying space, the way in which architecture is used in London to express class aggression, and more.

Occupied Chicago Tribune: There’s this recurring theme of the transformation of place in several of your novels. The Scar and Iron Council in particular seem to be partly about intentionally created, dissident communities that are made in an unusual location.

One of the things that set the Occupy movement apart from some earlier protests and actions was this idea of taking over a space, inhabiting it and changing it. As someone who’s observed Occupy, is there something particularly resonant about that change in tactics?

China Miéville: I’m extremely sympathetic to Occupy and I’ve been extremely impressed with the way the movement’s been able to shift certain ideological agendas with great speed and creativity. But I’m a supporter and a fellow traveler rather than someone who’s deeply involved.

In terms of the creation of what I suppose at different points in the history of struggle would have been called Temporary Autonomous Zones or dissident spaces, my feeling is they are often intoxicating to be in and can be quite psychologically liberating. I remember very much, as I mentioned in “London’s Overthrow,” simply walking through the occupied deserted bank in London in a constant state of almost giddiness. That kind of reconfiguring of space definitely can be psychically powerful and resonant.

But I do also think that strategy has costs as well as benefits. I would want to be cautious about it because there is a danger of insularity. Of course some movements strive against that, and strive to make connections with trade unions and other social movements.

But it’s also true that there can be a tendency towards a sense that the freeing up of this particular space becomes an end in itself and almost an attempt to create a little utopian space, and I would be quite skeptical of the resilience of any such space. I think the fact that it is inevitably hedged around and constrained enormously means that no matter how much it might be an enjoyable alternative space in any particular moment, it cannot in and of itself usher in a wider change.

It also remains extremely vulnerable. Without wanting to minimize the sterling efforts of many activists on the ground – you see how the reconfiguring of the space back again, for example in London, was not terribly hard, relatively speaking, when the authorities decided that enough was enough. That in and of itself is no criticism of the movement, but I’m not convinced that the reconfiguring of the space has long-lasting impact. I would see it as one possible and sometimes exciting strategic moment but I certainly wouldn’t prioritize it over industrial action, mass action, demonstrations, picketing.

OCT: An interesting thing has happened with Liberty Park, the name that Zuccotti Park had for the just under two months that the original Occupy Wall Street camp existed. Despite happening in a large American city, not very long ago, and being extremely media saturated in many ways, it’s become mythic incredibly quickly, in a slightly problematic way.

CM: Absolutely, and to a certain extent that’s not very surprising. Radicals are just as nostalgic as anyone else, if not more so, and that tendency towards sentimentalization and mythologization is very strong, and I share it and I understand it completely. But you’re quite right that it is often problematic.

It’s strategically extremely problematic because it mistakes a means for an end. If the point about Liberty Park was to be itself as long as it could last, then that seems to me to be a very limited goal. To the extent that it’s about pushing something else forward, that’s fantastic, I’m completely there. But if it’s about saying “we have this space, let’s make it thrive as long as it can,” then what about all the people who don’t have the luck to be able to access that space? What about the people who don’t have the economic freedom to take the time to be part of that space?

This is not, I want to stress, the reactionary critique of “oh, these are middle class kids playing at stuff,” I speak from nothing but solidarity, but a certain kind of unsentimental relationship with the limitations of these sort of autonomous zones is completely appropriate, as a part of allowing them to do well what they might be able to do well. If we start to have inflated notions for these spaces, then that doesn’t help them let alone a wider agenda.

OCT: I want to shift gears a little and talk about transformations of place from a reactionary standpoint. As someone from the United Kingdom who’s been living in the States for a few years, what has happened to the UK since the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition took power seems astonishingly fast to me, even in the context of what New Labour actually was.

The speed with which the Tories returned to power and then enacted a very right-wing agenda is almost apocalyptic, and it seems as if in London there are physical expressions of this. Is there a feeling of inherent badness on the ground, or are things not that different?

CM: No, I think you’re quite right, I am struck by “how fast, how bad” – I am, I am. This is partly generational: I’m 39, and anyone who is around about my age [Editor’s note: the author of this piece is 34] who was remotely politically active… some of us were really quite traumatized, understandably, by the Conservatives, so there really was a tremendously apocalyptic sense at that return.

After the election, I was speaking to a friend of mine who is also an activist and is considerably younger than me. I probably sounded like St. Anthony seeing a revelation of demons, I was saying “Oh my god, I can’t believe this” – and he gently chided me and said “yes, it’s bad, but people of your generation are more traumatized by this.” There’s almost a kind of frozen aghast-ness. Whereas he’s unhappy of course, but he doesn’t have that same kind of knee-jerk trauma. So I would want to sound that caveat, which is that none of this is a counsel of despair or misery or total disempowerment.

All of which said I also think it’s completely appropriate to be very level-headed and critical about this, and I think this is a startlingly bad time. The agenda of the ConDem government has been remarkably aggressive. I’ve been if anything somewhat surprised at how aggressive it is, and it does seem to be a deliberate scorched earth strategy of Thatcherism, to try to create facts on the ground fast enough that they can’t be overturned. There’s no point pussyfooting around that fact. There is a really baleful sense around, particularly in some of the areas being so dramatically reconfigured by the Olympics. The riots were a very concrete expression of that fact.

The disparity between the kind of crushingly banal, middlebrow rah-rah that stems out of Blairism and that David Cameron adopted, the disparity between that and a real sense of an ugly transformation on the ground is more dramatic even than it was under Labour, and I was of course no fan of New Labour. I don’t like the murmurment in London, I think it’s a really bad time. It feels ugly and it feels extremely aggressive in class terms, and it is worrying. I am not a political pessimist at all, and so I don’t want to seem like a gloom and doom merchant, but I do think there’s no avoiding the fact that there’s a fairly serious assault going on.

You really do see it in spatial terms. The corporatization of public space was going on very much under Blair, of course, and the reconfiguring of the city with these massive mega-projects was going on for some years. But in the context of the recession, which is combined very clearly and deliberately with a very deliberate act of class battle on behalf of the government and the neo-liberal agenda, that reconfiguring is much more palpable and dramatic than it has been, so there is very much a sense of things coming to a head.

What I was getting at in “London’s Overthrow” was a sense of reaching a point of trembling, a point of really potentially horrible shit. I don’t feel that we’re post-apocalyptic, but I certainly feel like we’re on the verge of something.

OCT: It seems like the veil has been taken away in terms of how malignant this stuff is, with something like The Shard. As you say, they were always being built, but suddenly it’s like there’s no pretense that this is for everybody’s benefit, it’s just big, ugly, sinister things in place.

CM: I think the psychic politics of the built environment has reached a point of extraordinary neoliberal kitsch. We’re entering an epoch where subtlety is of no use to the ruling class. And not just subtlety: If you look at Fascist architecture, baleful and terrifying as it is, it is steeped with some sense of grandiosity. What strikes me about a lot of the architecture that’s going up at the moment is its simultaneously kitsch-ness with a kind of banality.

It’s an incredibly banal dystopia, it doesn’t even have the fucking decency to have a Sturm und Drang grandeur about it, and the Shard is pretty paradigmatic of that.

But that particular kind of banal dystopia really does stretch back two decades. Anyone who thinks that this is new just needs to go to Canary Wharf, which for me remains the high point of this. You cannot exaggerate the unbelievable architectural “fuck you” to the poor that is embedded in Canary Wharf. I still think that it is the most unremitting act of embodied class aggression in the built environment of the city, and the Shard and all these others, for all that they attempt to sort of stamp their monied will across the face of the city, I still think they are also-rans next to Canary Wharf. Canary Wharf is an un-reconfigurable excrescence.

I can imagine an emancipated utopia which reconfigures the Shard, just about, I can imagine an alternative society which finds a certain type of beauty in some of this recent architecture. I cannot imagine an emancipated future in which Canary Wharf is not pulled to the ground.

In part 2: Why the left shouldn’t try to reveal truths or shake people’s illusions, and why we’re likely to see an increase in “crisis fiction” from authors of all political stripes.

Trump is silencing political dissent. We appeal for your support.

Progressive nonprofits are the latest target caught in Trump’s crosshairs. With the aim of eliminating political opposition, Trump and his sycophants are working to curb government funding, constrain private foundations, and even cut tax-exempt status from organizations he dislikes.

We’re concerned, because Truthout is not immune to such bad-faith attacks.

We can only resist Trump’s attacks by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser, and we must raise $31,000 in the next 4 days. Please take a meaningful action in the fight against authoritarianism: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout. If you have the means, please dig deep.