Part of the Series

The Road to Abolition

One of Borey “Peejay” Ai’s earliest memories is the sound of gunfire. “My mom would put us under the table,” he recalled. Ai was too young to understand what was happening, but he remembered being afraid like his mother. “Because I felt her fear, I felt fear too,” he said.

Ai was born in a refugee camp in Thailand after his mother fled Cambodia to escape the Khmer Rouge genocide. As a small child, he would climb a hill to water a pepper plant he had been growing. From the vantage point, he would look across the border and see people shooting at one another.

Nearly 40 years later, after surviving the brutality of the U.S. prison system, Ai now faces the possibility of deportation back to Cambodia, where he has never set foot. And he’s not the only one.

Tens of thousands have finished their prison sentences only to encounter an additional penalty applicable only to non-citizens — deportation. Some, like Ai, have never lived in the country to which they would be deported. Others, like Maria Legarda, face death if they are returned.

In California, Ai, Legarda and two other organizers with the Asian Prisoner Support Committee, Chanthon Bun and Nghiep “Ke” Lam, have all been granted parole by a board known for its high denial rate, but they now face deportation. All four are now hoping that Gov. Gavin Newsom will recognize their transformations and contributions to their communities, and allow them to stay in the U.S.

One of the State’s Youngest Juvenile Lifers

When Ai was 4 years old, his family entered the U.S. as refugees with permanent legal status. “Everyone told me I was lucky to go to the United States,” he told Truthout.

But the promised land didn’t hold much promise, especially in Stockton, California, where many Cambodian refugees suffering from trauma were resettled in poor areas plagued by drugs, gangs and violence.

At school, Ai was incessantly bullied and attacked by other children, who told him to go back to his own country. When he was in 1st grade, a gunman opened fire on his elementary school of mostly Cambodian and Vietnamese children. Ai survived; his 7-year-old cousin and four other children did not.

At 12, Ai turned to gangs for protection. Two years later, in 1996, Ai and three older gang members attempted to rob a liquor store. The owner grabbed for Ai’s gun. It went off, killing her. Ai turned himself in the following year.

Between 1995 and 2018, as politicians created fears of teenage “super-predators,” California allowed 14-year-olds to be tried as adults. In 1997, when he was just 16, Ai was sentenced as an adult to 25 years to life in prison, becoming one of the state’s youngest juvenile lifers.

In California’s youth prison, Ai taught himself to read — something he had never learned while in school. “I started to see the world differently through the books I was reading,” he recalled. He was one credit shy of his high school diploma when he turned 18 and was transferred to an adult prison. There, he got his GED.

He also connected with other men who invited him to programs in which he began openly talking about the traumas he and his family had faced. “I realized I’d harmed so many people,” Ai recalled. “I walked away from the gang.”

He enrolled in the prison’s college program. He became a certified rape crisis counselor and participated in restorative justice programs. He also connected with the Asian Prisoner Support Committee (APSC), an advocacy organization that emerged from demands for an ethnic studies program at San Quentin. Now, he works with the organization as a community advocate.

“I made a pledge to myself while I was in prison to make amends and give back to my community,” he said.

In 2016, Ai had his first parole hearing. The board typically denies more applicants than it approves, especially during initial hearings, but commissioners were impressed with his accomplishments and approved his release. Before Ai could walk through the prison gate, however, immigration officers handcuffed him and drove him to an Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention center where he spent the next 18 months. He was now under threat of deportation to Cambodia, due to U.S. immigration laws that allow non-citizens convicted of felonies to be deported.

While in prison, Ai had applied for a pardon, which, in California, would eliminate the conviction on which ICE bases its deportation order. While parole officials recommended that then-Gov. Jerry Brown grant the pardon, the state Supreme Court blocked it.

ICE was unable to secure travel documents to deport Ai to Cambodia. He might have continued languishing in detention, but sustained organizing by APSC helped secure his release, albeit with an ankle monitor, in 2018.

When Gavin Newsom became governor of California, Ai applied again for a pardon, which parole officials again are recommending. Now all Ai can do is wait and hope that this time, the court won’t block the governor from acting.

“Freedom From a Death Sentence”

Maria Legarda came to the U.S. from the Philippines at age 20. Her younger sister’s long, and unsuccessful, struggle with leukemia had left Legarda’s family saddled with debt and she hoped that her American wages would help lessen the financial strain.

Away from her family, isolated, and still grieving her sister’s death, Legarda began using methamphetamine. She was raped by a man she met online and became pregnant. Determined to have a healthy baby, she stopped using meth.

Toward the end of her second trimester, Legarda’s mother told her that, despite her remittances, her sister’s medical debt kept the family in perpetual poverty.

That same night, a friend offered her meth. “I remembered how being high seemed to take away all my problems,” Legarda told Truthout. She wasn’t thinking about the pregnancy, or anything. “There was no next day,” she recalled.

But the methamphetamine induced her labor and the next morning, Legarda gave birth alone in her bathroom. “He wasn’t moving, he wasn’t crying,” she said of her newborn son. She lay him on a towel and then, in shock, began getting ready for work as if she had not just delivered a baby. She called a taxi. The driver, noticing that she was bleeding in the back seat, brought her to the hospital. There, she told medical staff that she had given birth, but the baby had died. She was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to 25 years to life. (She was later resentenced to 15 years.)

Legarda was 25 when she arrived at the Central California Women’s Facility in 2004. “I came to the U.S. to help my family. How does me being in prison help them?” Legarda remembered thinking. “I knew I had to do something different.”

Older women serving life in prison pushed Legarda to take an anger management class. That three-day class opened the door for her to begin exploring her family’s traumas — and her own journey toward self-understanding.

“Going through those [prison] groups helped me understand me and get to know who I am,” Legarda recalled. For instance, when asked her favorite color, Legarda had no answer. “It’s a simple question, but I didn’t have an answer for it because I didn’t know who I was.” She later learned that she preferred gray.

She also became involved in other programs, including projects that directly helped children. “I wanted to do something I could never do for my son,” she said.

In 2019, she appeared before the parole board, which approved her release. She was one of 75 women (less than one-third of the 267 women applicants) to be granted parole that year in California.

But upon her release from prison, Legarda was immediately transferred to ICE detention, where she spent 11 months. In 2020, because her asthma placed her at high risk for fatal or severe COVID-19, ICE released her with electronic monitoring.

Legarda still faces deportation. Given the Philippines’ ongoing anti-drug campaign, in which police have killed thousands of people suspected of drug use, deportation brings the imminent risk of not only arrest, but death.

It does not matter that Legarda has not used drugs for over 20 years. Under the current regime, Legarda explained, “there’s no ‘was a drug addict.’ You’ll always be [considered] a drug addict.”

Fearing for both her own and her parents’ lives if she is deported and must live with them, Legarda applied for a pardon in September. Her application now goes to the parole board, which will decide whether to recommend that the governor pardon her.

While she waits, she works with APSC to connect others coming home from jail or prison with services and reentry needs, such as housing. She tells them about the 14 years she spent in prison — and hopes her story encourages them not to give up.

“A pardon would mean that I would not have to live in constant fear of being deported in a country where my life is at risk of execution and I would be able to live here in the U.S. without having to look over my shoulder for the rest of my life,” she said. “Getting a pardon would mean freedom from a death sentence.”

“Still in That State of Limbo”

In 1993, Nghiep “Ke” Lam was 17 years old when he fatally stabbed a rival gang member. He was sentenced to 27 years to life.

Two years later, in 1995, immigration officials visited him at San Quentin prison. That was when Lam learned that he had not been born in the U.S., as he had always assumed, but had fled Vietnam with his family when he was 2 years old, spent two years in a Hong Kong detention center and came to California at age 4. His conviction, an aggravated felony, subjected him to a deportation order after his prison term ended.

Like Ai, Lam was one of thousands of teenagers sentenced as adults. At San Quentin, he met dozens of other juvenile lifers. Their lack of life experience counted against them in the prison’s classification system. “If you’ve never gotten your high school diploma or GED, never done military service, all of these extra points are added to us,” Lam told Truthout. Those points classified them as higher security risks and teenagers were often sent to more restrictive prisons with fewer programs and more violence. Later, the same lack of experiences — and program participation — counted against their chances of parole.

In 2003, Lam was transferred to San Quentin. He began thinking about his first parole hearing. By then neuroscientists had concluded that the human brain, including its capacity for impulse control, was not fully developed until a person’s mid-20s, and the U.S. Supreme Court would soon prohibit mandatory life without parole sentences for those under the age of 18. But California parole board members still treated juvenile lifers as if they had been full-grown adults when they committed their crimes.

Lam and other juvenile lifers were determined to change that. They met with attorneys from Human Rights Watch and later with state legislators. The results were two laws, SB 260 and SB 261, creating youth offender parole hearings for people whose crimes happened when they were 23 or younger, and directing the parole board to give “great weight to the diminished culpability of juveniles.”

“It’s not a ‘Get Out of Jail Free’ card,” Lam explained. “You still have to be responsible and accountable for what you’ve done.”

In 2015, Lam appeared at his own youth offender parole hearing and was granted parole. But he was immediately transferred to ICE detention, where he spent five months.

Seven years earlier, in 2008, the U.S. and Vietnam had reached an agreement limiting U.S. deportations of Vietnamese refugees who entered the U.S. before July 12, 1995. That prevented Lam’s detention, but left him a stranded deportee, in that neither country offers a path to permanent residency.

That hasn’t stopped him from starting to build an adult life. “Prison is a time capsule,” he said. “I came home with the mindset of a 17-year-old.” He had to learn not only all the technology that he had missed, but also basics like paying bills, finding work and opening a bank account.

He now works with APSC, helping steer others through the same puzzling path of reentry and addressing intergenerational traumas. “There is silence in our community, but we don’t have to remain voiceless anymore,” Lam said.

Shortly after his release, he reconnected with a high school acquaintance. They are now engaged and Lam is helping raise her 6-year-old daughter. Still, the specter of deportation haunts his future.

“My hesitation in getting married is my status,” he said. “I’m still in that state of limbo.”

Lam applied for a pardon this past summer, which he said would bring a sense of relief not only to him, but to his extended family, including his mother, six siblings and seven nephews and nieces. “They don’t have to worry that their son, fiancé, brother and uncle won’t be around,” he said. “And it allows me to continue the work that I do.”

“Should I Stay Quiet?”

Shortly after his 18th birthday, Chanthon Bun participated in a robbery. He was arrested and sentenced to 49 years and 8 months in prison. The flat sentence meant that he had no chance to appear before the parole board to plead for an earlier release. To the teenager, being imprisoned nearly 50 years was a lifetime.

“I gave up,” he told Truthout. He no longer cared about consequences and, when he was 27, he was sent to solitary confinement for five years.

While in isolation, he learned his beloved grandfather had died. People in solitary are typically not allowed phone calls, though exceptions are made when a family member dies. When he wrangled a call to his mother, she told him, “Even to his last breath, he wanted you to come home.”

“I thought back to all his teachings,” Bun recalled. Bun’s grandfather had been a lifelong Buddhist and, before starting a family and fleeing the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, had been a monk. In the refugee camp and in the U.S., he had raised Bun like a son. “What would he want his only grandson to do?” Bun wondered.

When Bun was arrested, he left behind two sons — a 6-month-old and one yet to be born. His grandfather’s death pushed him to rethink his relationship with them. “Even if I die in prison, I shouldn’t give up on my kids,” he thought.

In solitary, lacking access to programs or books, he leaned into his grandfather’s teachings, taking up meditation and learning to calm his mind. When he was released from solitary, he was determined to change, but the maximum-security prison offered few opportunities.

Shortly after he transferred to a prison with more programs, he learned that his older son planned to drop out of high school. “Why should I graduate high school when you didn’t?” the teenager asked.

That prompted Bun to get his GED.

Then he asked his older son about college. “I asked, ‘Are you going to college?’ and he asked me the same question,” Bun recalled. Both father and son enrolled in college.

Still, Bun wasn’t thinking about his own future. “I was doing this all for my sons,” he said. “Once they grew up and could take care of themselves, my life didn’t matter anymore.”

Then SB 260 passed, bringing hope for a future. Bun had to wait until the board had held hearings for all juvenile lifers, but that gave him time to enroll in programs, including one offered by APSC that allowed him to explore the intergenerational trauma that his family had been through. He also learned several trades, knowing that he needed to prove that he could land a job and support himself after he went home.

In February 2020, Bun appeared before the parole board, which approved his release.

Then COVID hit San Quentin. “The whole place was sick,” Bun said. “People were dying, the prison was on lockdown.”

Less than two weeks before his release, an ICE agent came to San Quentin to tell Bun that he would be transferred to ICE detention. Shortly after, Bun’s temperature soared, his body was racked with chills and he was hallucinating.

“We heard stories that if you got COVID, they wouldn’t let you go home,” he recalled. Determined not to lose his release date, Bun flushed his mouth with cold water every morning before the nurse took his temperature.

On July 1, Bun waited for ICE to pick him up. Members of the Asian Prisoner Support Committee gathered at the prison’s back gate, where ICE usually brought people out, to protest his detention.

Immigration agents never showed up. Instead, prison staff drove him to the nearest bus station, handing him a debit card which he had no idea how to use. He had no way to contact the APSC organizers still waiting at the prison’s back entrance.

Finally, he boarded a bus to San Francisco. He was feverish and hallucinating and, at some point, passed out. When he woke, he asked a passing construction worker to call his attorney. He did and explained where Bun was, allowing APSC organizers to find him. They bundled him into a car, covered with protective plastic, and took him to get tested. Then, they found him a small house where he could isolate.

“It was the community coming together to save my life,” Bun recalled.

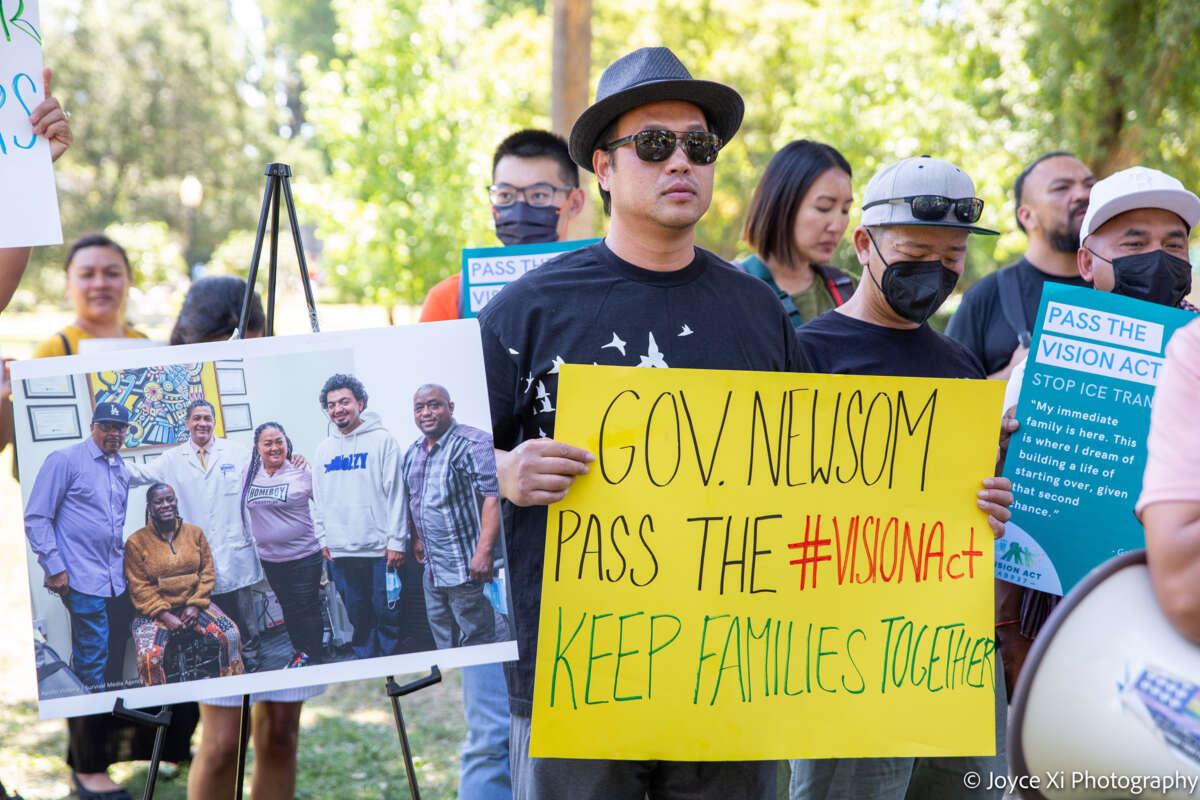

Bun now works with APSC advocating for immigrant rights, including pushing for the VISION Act, which would stop prison-to-ICE transfers. (The act fell three votes shy of passing.) He still has an ICE warrant and can be detained at any time. Every day, he faces the question: “Should I roll the dice and see if they pick me up? Or should I decide to stay quiet?”

Bun’s older sons are now in their 20s and have children of their own. Bun now has a 1-year-old son, too — and the thought of being torn from the toddler brings him to tears. A pardon would keep him with his family — his three sons, his grandchildren, as well as his mother and four younger sisters.

Despite the risks, Bun continues speaking out, determined to change the narratives around crime, safety and second chances.

“We came to this country with a lot of trauma from genocide, then from living in poverty, living in a country that you don’t understand anything about and living with parents that are traumatized,” he said. “A lot of us were incarcerated as children. We went through a lot of life lessons and we have changed. We’re not kids no more and we’re not the crimes that we’ve done.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. We have hours left to raise the $12,0000 still needed to ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.