Honest, paywall-free news is rare. Please support our boldly independent journalism with a donation of any size.

I met Nomi on a bus in Baltimore. She was from Wisconsin and had been involved with Occupy Wall Street. She was part of Occupy Judaism and fondly recalled the Yom Kippur services she attended at the Wall Street occupation with hundreds of other people. Nomi said that, for the first time, she and her friends felt like they could combine the religious and radical dimensions of Judaism. The conversation fell silent as the bus rolled along. Suddenly she turned to me and excitedly announced that she met her girlfriend at Liberty Plaza. I smiled and responded, “That’s why Occupy Wall Street matters.”

By enabling people to find fulfillment in all parts of their lives, whether romantic, spiritual, political or cultural, the Occupy movement is more than a movement. It is life-changing. People experience themselves as complete social beings, not just as angry, alienated protesters. Nomi said she was no longer involved in the movement, which I thought was more evidence of why the actual occupations were so important.

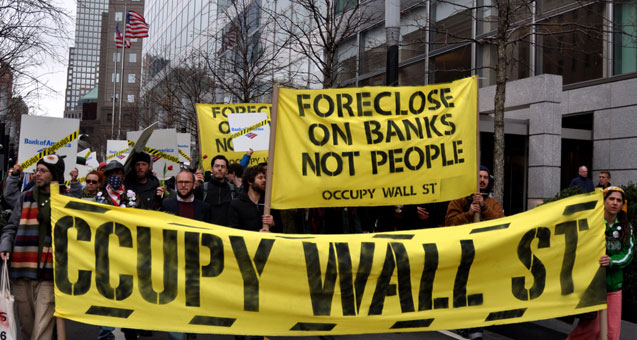

The emergence of every mass movement makes sense in hindsight, but no one could have predicted hundreds of occupations and thousands of groups would pop up across the United States just weeks after a ragged encampment secured a tenuous foothold on Wall Street last September. Sure, anger was boiling over prior to the takeover of Zuccotti Park in downtown Manhattan, but the occupation crystallized who is to blame for the economic crisis and who are the legitimate people. Anyone could walk into the public space, share their stories, find people with similar grievances and help build micro-societies. Occupy wasn’t just a rejection of Washington and Wall Street. It revealed the failings of liberals, unions and the left. New activists didn’t first have to master volumes of social and cultural theory, attend grueling anti-oppression workshops and learn how to pepper their comments with academic jargon before joining. Nor did the movement require consultants, focus groups or polling to occupy the center of American politics with a radical left message. And the form was not the same old rallies with canned chants, pre-printed protest signs and preaching to the choir.

It’s worth considering why Occupy Wall Street was such a smashing success last fall, as well as where it is headed. While the media lens has shifted away, Occupy has spawned a menagerie of energized movements and ambitious plans. Veteran organizer David Solnit, who is involved with Bay Area Occupy movements, sums up the current state: “The numbers showing up at GAs have dropped. Any movement has its mass mobilization and its in-between times. The organizing a lot of people are doing around housing and education are less visible but go much deeper. We need a better measuring tape than numbers and public space and whether it’s amplified through media owned by the 1 percent.”

Like plants that lay dormant for the winter conserving energy, many occupations are blossoming anew with ambitious plans now that it’s spring. Solnit says in San Francisco the movement is defending a dozen families in foreclosure, and is working toward a citywide moratorium on bank foreclosures and evictions. In Los Angeles, organizers say May Day plans include large-scale marches by immigrants and unions, rolling street blockades and even an attempt to disrupt the main airport. In New York and around the country, a campaign has been launched called “F the Banks” to force the government to dismantle Bank of America, which is still receiving taxpayer subsidies. In Chicago, after the G8 summit set for May was moved to Camp David because of fear of large-scale protests, activists are moving forward with large-scale demonstrations to coincidence with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) meeting the same month.

Challenging the status quo comes with costs. As the Occupy movement struggles to effect radical social change, it faces persistent police attacks and co-optation by Democratic Party forces from the outside and divisions over identity politics, militancy, localism and diffusion from the inside.

Rethinking Democracy

Occupy Wall Street is foremost a democratic uprising from the left because it advocates for the downward and outward distribution of wealth and political power. Tying political democracy to economic democracy has made class relevant again for millions of people. As for the form, occupying public space is an old tactic. Since the early 20th century, examples include the Wobbly free-speech campaign, the automobile factory sit-down strikes, lunch-counter sit-ins, the Columbia University student takeover and Cindy Sheehan’s vigil outside of Bush’s Texas ranch. The need for democratic forums is greater than ever as public space is ever-more surveilled, regulated and commodified.

Occupy also challenges the notion that workers are the sole agent of revolution. Clearly, labor’s power is unmatched in potentially bringing capitalism to a halt, but in actuality, collective action on the shop or office floor has been crippled by a lack of working-class consciousness, timid and self-serving union bureaucracies, and the legal and repressive tools of the corporate-state hybrid. Occupations of public space by activists, intellectuals and marginal workers – as shown by Egypt’s Tahrir Square, Oakland’s November 2, 2011, general strike and the December 12, 2011, West Coast port blockades – can attack capital from unexpected directions, creating space for organized labor to take more militant action.

In terms of development, the Occupy movement has gone through a series of stages, though they are not so much distinct phases as overlapping and intermingling trends where one stage may take prominence over the others at different times. First, the occupation created an awareness of a group that could be called “the people,” which is often invoked with the now-ubiquitous chant, “We are the 99 percent.” The flipside of “the people” is those who are not a legitimate part of the community: “the 1 percent,” in this case. Both categories are social and psychological concepts that mobilize rather than analytical terms that accurately describe social forces. Segments of the 99 percent, such as white-collar managers, small-business owners and the police, generally act as the social and physical enforcers for the elite, while the real owning class is perhaps the top .01 percent. But “We are the 99.99 percent” is hardly a catchy slogan. In this respect, Occupy Wall Street is similar to the Tea Party, which invokes its legitimate community with slogans like, “We the people,” “Take back America” and “Founding Fathers.” For Tea Partiers, however, nearly everyone else is illegitimate – unions, immigrants, Muslims, liberals, welfare recipients (code for blacks and Latinos), feminists, environmentalists, socialists, and gays and lesbians.

Combine a public organizing space with “the people,” and the second stage follows: assault the citadels of illegitimate power. As one organizer told me about Zuccotti Park, “At any moment, you could call for an impromptu march on Goldman Sachs and a hundred people would join you.” The night of October 5, 2011, was an exhilarating example of this. After a union-led rally in downtown Manhattan, thousands of people surged through the financial district in breakaway marches for hours. With so many people in the streets feeling the wind of public support at their backs, the police were taxed to hold the line. Wall Street was no longer an impenetrable bastion and the New York Police Department (NYPD) was no longer omnipotent. They felt fragile and under siege.

The occupation was a focal point for the media as well, and, surprisingly, many corporate media outlets gave the movement favorable press at times. Some observers have suggested that one lesson is not to see the corporate media as the enemy. Rather, it should be treated as a battleground, albeit one that is tilted toward the interests of the wealthy and the imperial state. The physical occupation also served a valuable role in making, “politicians realize there are people watching what they are doing,” says Anne Gemmell, political director of the labor-backed community group Fight for Philly.

“You Have to See to Be Able to Dream”

The third stage is carnival. After years of clichéd protests bearing witness to power, street politics had become futile and predictable. Leaders of the anti-Iraq War movement excelled at polite marches on weekends with no risk and little impact, and adjusted its politics to the election cycle, leading to its demise by 2007. Occupy Wall Street hit the big time because it is innovative political theater, a quality shared by the civil rights movement, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), the global justice movement and the Arab Spring before it. I would stand on the steps of Zuccotti Park and watch as hundreds of people below exchanged food, art, knowledge, books, politics, health care, bedding, anger, ideas, skills and love. Not one exchange was mediated by money (of course, the goods were paid for at some point). It felt like being able to breathe for the first time, because relations were being forged according to human needs and concerns, not according to the logic of the market. Revolutionary consciousness was being born through collective, democratic political action, which is essential to igniting a new era of activism and organization.

The occupation made a different world real, one without corporations, authoritarian politics and the police state. As Michael Premo of Occupy Wall Street’s housing group, puts it: “You don’t know how to dream unless you see it sometimes. The occupation unlocked the creative, radical imagination.” Seeing new and different ways of organizing work, family and community drew throngs of first-time as well as wayward activists to the movement. If it was the left organizing the left, Occupy Wall Street would have failed because experienced activists, no matter how well intentioned, come bearing heavy allegiances, ideologies and interpersonal baggage that inevitably sink left re-foundation projects. A movement must coalesce around the previously nonpolitical to forge meaningful social change.

Whose Community?

The fourth stage is creating genuine community. The cultural life of occupations and the experience of working and living together bonded occupiers together. What community involves is thorny, however. For example, at the occupation in Portland, Oregon, organizers say the encampment diverged from the general assembly because those sleeping in the park, many of whom were homeless, were not present at the general assembly meetings, also known as GAs. As a result, the GA was approving decisions about the occupation with few actual occupiers present. A related case occurred in Austin, Texas, where one organizer told me that, by December, the GA was trying to end the encampment on the steps of Austin City Hall, while the occupiers, again mainly homeless, blocked the action because they said they had no other safe place to live. (Eventually, the city of Austin shut it down by force in early February.) Other cities encountered a similar phenomenon, and frequently enough that “home-based occupiers” is now a common term used to refer to those who are active in the movement but do not sleep in the camp.

The idea of community is also a proxy for long-simmering debates over whether the goal is to take over the system or to build a new world in the shell of the old. As occupations and enthusiasm spread, many activists yearned to construct sustainable economies to meet the needs of daily life. Occupations ran on their communal stomach, so community gardens, recycling and grey-water systems were often first on the agenda. It didn’t take long for the dreams to outrun reality, however. Last fall, I was approached by occupiers looking to form a printing cooperative. They planned to start with photocopies and progress to newspapers such as The Indypendent and The Occupied Wall Street Journal, both of which I co-founded. I was stunned. Photocopying flyers is one thing, but printing 50,000 copies of a four-color newspaper is another. I explained it would require a warehouse-sized space, millions of dollars in capital, sophisticated press equipment and digital technology, experienced workers to run the facility and business savvy to survive in a printing industry with razor-thin margins. I never heard from them again. Currently, many occupations are pursuing small-scale projects such as urban farming and communal living, but this runs the risk of utopian separatism. The dream of gathering the righteous and starting anew in uncharted territory or creating a new social space is the story of America, after all. Withdrawing from society is tempting, but a sign of defeat.

Now that nearly every occupation that popped up last fall has been evicted from their common space, it’s tempting to say that “Occupy 2.0” is underway. There are energized movements around housing, finance, labor, food, art, gender and ecology. Nonetheless, the loss of public space is an undeniable setback: it glued the movement together.

Nathan Schneider, who has chronicled Occupy Wall Street from the pre-planning stages, says that, since the occupation was routed from Zuccotti Park, decisionmaking power has devolved from the general assembly to the spokescouncil to working groups to campaigns. In March, I queried about 15 Occupy Wall Street organizers, and not one had been to a GA meeting in the prior month. Some rolled their eyes at mention of the GA and told of constant disruptions and occasional fistfights. A few claimed paid provocateurs were stirring up the pot. No one could offer any proof of government agents, which is admittedly difficult to come by, but the infighting is all too real. When hundreds were living on Wall Street’s doorstep, the target was obvious: banks like Goldman Sachs and their lapdogs in the media and politics. Without an occupation as an anchor, vessels like the general assembly and spokescouncil can drift aimlessly, making it tempting to turn on your fellow crewmates.

With the occupations over, most newcomers have wandered away. Ruth Fowler, a writer who works with Occupy Los Angeles, says: “Occupy is very odd right now. The people who have stayed are the cream of the crap, and the brilliant. The rank-and-file in between are at home … It’s an interesting dynamic. Not entirely comfortable. Lots of loonies floating around.”

The lack of community means struggling with who is the subject and what is the purpose of the decisionmaking bodies. Michael Premo of Occupy Wall Street says organizers understand there is a need for physical space, “to build on the things that worked and think about what didn’t work.” He adds that Occupy Wall Street is, “planning on creating a clearinghouse for people to come together, build community and organize actions.”

The Roads Ahead

New York is a showcase for the possibilities and pitfalls of Occupy Wall Street, which still bubbles with creativity. On March 28, Occupy Wall Street (claiming support of transit workers) took credit for chaining open 20 subway stations, allowing thousands of straphangers to ride for free so as to call attention to Wall Street’s profiteering off of the city’s perpetual mass transit follies. On March 15, a few hundred people outfitted with songs, banners and facades of foreclosed homes and costumed as bankers and police joined “F the Banks.” At turns festive and angry, the procession snaked through downtown Manhattan, halting at bailed-out banks to deliver a dose of displeasure. The highlight was an attempt to occupy a Bank of America branch with furniture. It being New York, police pounced as sofas, tables and bookcases were arranged outside the bank. Within minutes, scores of cops had quarantined the area and were carting away a handful of smiling protesters in cuffs.

The police strategy is to suffocate any outbreak of democracy, and it shows signs of working as long as the rank and file has vanished. Elites want images of heavy-handed policing because the narrative shifts from inequality to streetfighting, scaring off potential supporters. On March 17, the six-month anniversary of Occupy Wall Street, a completely peaceful attempt to re-occupy Zuccotti was aggressively evicted. The occupation shifted to Union Square, but after a few days, hundreds of police swept in to enforce rarely employed restrictions on overnight activity. Other than a protest against the killing of Trayvon Martin, most recent Occupy Wall Street events have attracted less than 500 people. (In the case of the Martin protest, criticism was rife that some occupiers tried to turn it into an Occupy event to retake space, rather than focusing on police violence against and profiling of communities of color.) The protest-a-day mode can backfire because police swarm smaller protests, however peaceful and theatrical they may be. The antidote is greater numbers, but because any working group or campaign can call a protest, the movement risks spiraling downward into diffusion, unsustainable activity, burnout and shrinking crowds.

Occupy Comes Home

Despite these problems, Occupy has an enviable brand, significant public support, a plethora of movements and an unqualified success in reorienting the national debate from austerity to inequality. The secret of Occupy Wall Street’s strength is disrupting power in ways both simple, such as the “mic check,” and grand, such as by occupying public space. Even if that space is now a rarity, Occupy Wall Street retains a disruptive capacity that defies prediction. It can be seen from Occupy the SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission), which released a stunning 325-page critique of the Volcker Rule (which seeks to curb banks from gambling with government-insured money), to Occupy Our Homes, which has successfully engaged in dozens of successful foreclosure and eviction defenses nationwide since November.

These are symbolic victories that put financial regulators on notice that they are being watched, and they are real victories that keep families in their homes. Victories are essential because they sustain the movement. Occupy Our Homes has pioneered singing demonstrations to disrupt public auctions of foreclosed homes, having closed down two in Brooklyn in recent months, and the tactic is spreading throughout the city and country.

Beth Stephens and Annie Sprinkle, artists and social justice activists who describe themselves as “eco-sexual domestic partners,” have made their Bay Area neighborhood of Bernal a model of the anti-foreclosure movement. Their movement began out of “neighborly love” for a 72-year-old African-American homeowner and veteran who is facing eviction. They say David Solnit was the catalyst, introducing them to two dynamic organizers – Buck Bagot and Stardust (in Human Form) – who helped them found Occupy Bernal to defend homeowners. Stephens said: “The heart of the group is door-knocking. We have a list of foreclosures, and once a week, members go out to these homes and tell them we will help.” Stephens says 85 households, mostly of people of color, are facing foreclosure in their area, and Occupy Bernal explains they can assist them with free legal help.

“We are trying to mitigate the shame in this,” Stephens says. “If they don’t feel shame, they can understand where the blame is. They’ve been taken of advantage of by the banks.” She adds that Occupy Bernal is actively defending 13 homeowners against eviction, has disrupted auctions and protests regularly – including in a group called “wild old women” who are in front of the banks every week – but the threat of eviction remains. So Occupy Bernal is pushing the San Francisco City Board of Supervisors “to pass a resolution calling for a moratorium on all foreclosures until the big banks are investigated” for fraud in lending and foreclosure activity. Sprinkle emphasizes that while the work is “deadly serious, we are also having fun doing it.”

Nonetheless, the anti-foreclosure movement has a long way to go compared to the scale of the problem today, with 4 million families having lost their homes to foreclosures since 2007, and compared to the scope of resistance in the past, with some historians claiming that, during the first eight months of 1932 in New York City, 77,000 evicted families were moved back into their homes by activists.

Laboring for Victories

To notch far-reaching victories, the Occupy movement needs allies with millions of members and access to resources. In short, the beleaguered labor movement, which has found a lifeline in Occupy. Organized labor seems to understand that laws and court rulings have blunted its most potent weapon: the strike. Labor organizers across the country are unbridled in their support for the movement, saying occupiers can take risks unions are unable or unwilling to. Gemmell of Fight for Philly says, “There are no leashes holding the energy of the Occupy movement back.” She says it has had a “positive spillover effect,” and cited two instances where workers settled contracts on better-than-expected terms while Occupy Philadelphia was entrenched outside City Hall. Occupy Wall Street was a factor in the repeal last fall of Ohio’s law that would have decimated public-sector unions, though the tens of millions of dollars labor poured into the effort did not hurt.

By moving beyond the workplace as the locus of struggle between labor and capital, Occupy has introduced creative tensions that benefit unions even if they feel their toes are being stepped on. The December 12, 2011, West Coast port shutdowns organized by the Occupy movement generated friction with leaders of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU), who opposed the blockade attempts from Long Beach, California, to Vancouver, Canada. Occupiers then began organizing flying pickets to help the ILWU block a union-busting ship scheduled to come into Longview under military escort. Paul Glavin, an Occupy organizer in Oregon, says various occupations were “going to send hundreds of people, if not more.”

“It was going to be very big,” said Glavin. Before the confrontation occurred, grain export terminal operator EGT blinked and signed a contract with the ILWU.

The next test for labor and Occupy is May Day, with Occupy Los Angeles calling for a general strike. Michael Novick, a retired school teacher and anti-racist organizer, says, “There is a bunch of labor actions for May Day in LA,” including one by recycling workers in San Fernando Valley and possibly at attempt by workers to disrupt traffic to LAX, the most active airport on the West Coast. Students are discussing shutting down a freeway, and Novick says there will, “be two different immigrant rights marches in downtown, which reflects a lot of historical divisions in the movement.”

“Occupy is doing a car and bike caravan moving slowly across L.A. from four different directions,” said Novick.

One troubling development is the formation of a “99 percent table” by Los Angeles labor organizers who are allegedly siphoning unions and faith-based groups away from the Occupy movement while also excluding some members of Occupy Los Angeles who have criticized as what they see as attempts to poach the movement. Novick says Occupy’s strategy is to work with everyone, and the day will end with an occupation of some sort in downtown Los Angeles.

Many other cities are gearing up for a range of marches and protests on May Day, though anything approaching a general strike seems highly unlikely.”Occupy Portland is planning for a spring offensive with May Day as the focus,” said Glavin. “The Portland Liberation Organization Council is organizing to take over a building May 1. May Day will be part of a longer struggle. The strategy is to get organized in working-class neighborhoods to work toward a general strike.”

Austin, Texas, is a different story. Dave Cortez, a community organizer whose focus is on energy and jobs, is part of Occupy Austin’s working group on banks. Since Occupy Austin was cleared off the City Hall steps in early February, activities include organizing local, small businesses and nonprofits to move their money from Wall Street banks to community institutions.

“We are working toward getting the city, the county government, the transportation and school board to shift their money from the big banks to credit unions, and local banks,” said Cortez. “Since October, we’ve tracked $1.6 million moved from largely personal accounts into credit accounts.” But as for May Day, “We are one of the few Occupy movements not calling for a general strike on May Day. We’ve built a large coalition of immigrant rights, socialists, students, communities, faith, anarchists and environmental groups.” Cortez says union members support Occupy Austin, but it does not have any official union support. “It was clear from the get-go we would not be able to get buy-in for a general strike. It’s difficult for workers to participate because Texas is a right-to-work state. If they called in sick and participated, they could very easily be fired.”

Occupy and organized labor may also find themselves on opposing sides as unions throw money and troops into President Obama’s re-election battle while Occupy Wall Street mobilizes to occupy the Democratic National Convention, and the Republican counterpart, as well as making its presence known on the fall campaign trail.

Occupy the Election

When Occupy became a national sensation, Obama and the Democratic Party tried to co-opt it, which failed. At this point, the liberal strategy is more sophisticated. Democratic Party front groups like MoveOn and Rebuild the Dream have glommed on to the “99 percent,” trying to steal Occupy’s thunder while distancing themselves from the movement. Obama, meanwhile, is running even farther away by employing squishy language about “economic fairness” while Democrats are delighted that Mitt Romney is all but assured of the Republican nomination. Organized labor and liberals are already branding Romney as “Mr. 1 Percent,” as if Obama isn’t a gold-plated member of the 1 percent or been their greatest benefactor during the last three years.

Having interviewed hundreds of occupiers across the country, it’s fairly safe to say they fall into three camps regarding the 2012 election. There are those who didn’t support Obama in 2008 and certainly won’t this time; those who voted for him last time, but say they will not this time; and the plurality, those who say they will hold their nose and vote for Obama. Few occupiers, if any, will join Obama’s campaign, because all agree that the electoral system is broken, which is exactly why they flocked to the movement as an alternative method of building and leveraging power. But at the same time, the Occupy movement needs to create a compelling counternarrative to the electoral process. It could be sidelined if it adopts a knee-jerk “pox on everyone’s house” response and tries to occupy the Republican and Democratic National Conventions in the face of certain police thuggery.

There are some in the movement who do want to enlist in policy battles and electoral campaigns, but visiting an active occupation affirms that the heart of the movement is about creating societies that embrace the limitless possibilities of everyday life instead of allowing our passions to be manipulated into support for a venal system and our desires to be ground into grist for cheap trinkets.

In February my partner, Michelle Fawcett, and I heard Occupy Fullerton in Orange County was holding an “Occupalooza.” It was a warm, sunny day, like it almost always is in the O.C., so we cruised Fullerton’s banal architecture until we happened upon an incongruous tent village. It was a familiar scene: about 40 tents, most shielded by blue tarps, and small knots of people playing music, smoking and lounging in the afternoon sun. The party was on top of the hill overlooking the Occupy Fullerton Camp, we were told.

Before hiking up the hill we met Wolf, a 25-year-old transgender native of Fullerton. Wolf was new to the movement, yet already immersed in it. He explained how Occupy Fullerton is lobbying the City Council to pass resolutions on issues ranging from Citizens United to predatory debt. His cool-headed explanation of how credit card companies trap unsuspecting college students in a cycle of debt gave way to a passionate embrace of the Occupy movement as a welcoming space for him and his intersex partner.

As we interviewed Wolf, John Park hung on the edge. When we turned to talk to Park, a Korean-American with two children in college, he launched into a blistering critique of the ideology of free trade, expertly citing the academic literature on the subject. That a middle-aged, immigrant computer programmer who is organizing around the outsourcing of jobs has found common cause with a transgender youth activist speaks to the raw ideological and emotional power of the twin slogans, “We are the 99 percent” and “Occupy Wall Street.”

When we clambered up the hill, we found a bowl-shaped grass amphitheater fringed by palm trees, a house band jamming with a few dozen people grooving to the music. True to the California setting, there were frisbees, sun bathers and stoners. Since it was winter, kids were sledding, even though that meant bouncing along a dirt gully gouged from the hillside. Lupe Barrios, eyeing our camera and notepad, sauntered over to talk. He said he was from Tucson, his right calf proclaimed “Hecho en San Diego” and he was here for “fun, not politics.” But within a minute, he was talking about how, “immigrant rights are workers’ rights,” and told us, “My mother lives in a cage wherever she goes because of social and class oppressions.”

The party was festive and giddy and unpredictable. The left is abundant in anger; the Occupy movement has turned that into joy. This country is floundering in despair; Occupy has given countless people hope. Within the Occupy movement, questions of inclusiveness, cooperation, compassion and democracy are foremost on people’s minds. People want work, but they want it to be meaningful. They want the good life however they define it: liberatory, intellectual, libidinous or spiritual.

These emotional and philosophical truths make all the difference. If the movement becomes predictable, the faces all look familiar and the organizing feels like drudgery, then it will have lost. For now, no one knows what will happen next. And that’s a wonderful thing.

Arun Gupta is covering the Occupy movement nationwide for Salon. A version of this article is being published in the May 2012 issue of Z Magazine

Media that fights fascism

Truthout is funded almost entirely by readers — that’s why we can speak truth to power and cut against the mainstream narrative. But independent journalists at Truthout face mounting political repression under Trump.

We rely on your support to survive McCarthyist censorship. Please make a tax-deductible one-time or monthly donation.