Part of the Series

The Road to Abolition

Captive Genders: Trans Embodiment and the Prison Industrial Complex (available to order with a donation to Truthout) brings together trans, queer and gender nonconforming views on police and prisons. Its pages brim with anger, grief, hope, humor and daring, taking on everything from bathhouse raids to capitalism, from prison rape to sex offender registries.

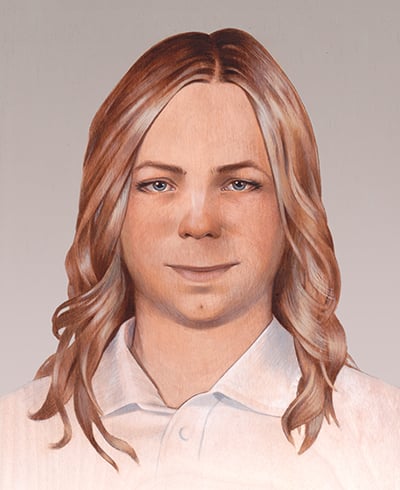

How Chelsea Manning sees herself. (Art: Alicia Neal / Chelsea Manning / Chelsea Manning Support Network)The first edition came out in 2011. Since then, between Laverne Cox’s role in “Orange is the New Black” and Chelsea Manning’s high-profile court martial, trans prison issues have catapulted into mainstream public consciousness. But trans and queer folks struggling in and against prisons is nothing new. Captive Genders gives us a window into this legacy of resistance. And more than that, it transports us to intoxicating possibilities for the future.

How Chelsea Manning sees herself. (Art: Alicia Neal / Chelsea Manning / Chelsea Manning Support Network)The first edition came out in 2011. Since then, between Laverne Cox’s role in “Orange is the New Black” and Chelsea Manning’s high-profile court martial, trans prison issues have catapulted into mainstream public consciousness. But trans and queer folks struggling in and against prisons is nothing new. Captive Genders gives us a window into this legacy of resistance. And more than that, it transports us to intoxicating possibilities for the future.

For me, CeCe McDonald’s foreword alone makes the second edition priceless. When McDonald defended herself from a racist and transphobic attack, she got arrested and charged with homicide. She cites that moment as the beginning of her own political education. In describing her time in prison, she casually demolishes stereotypes of incarcerated men. In her experience, anger and deceptiveness came from staff more often than prisoners. Additionally, McDonald gives us a glimpse of a gorgeous “trans-topia” – the world waiting for us when we have ended murders of trans women of color and ended prisons altogether. And she tells us the way we need to work to get there.

McDonald’s piece is not the only extraordinary addition, though. Kalaniopua Young traces the role of settler colonialism through the history of Hawaii and her own life as a Native trans woman. Chelsea Manning reflects on the interests and biases behind both military and prison systems. Janetta Louise Johnson and Toshio Meronek map the concrete harms prisons continue to inflict on trans women long after they get released.

McDonald gives us a glimpse of a gorgeous “trans-topia” – the world waiting for us when we have ended murders of trans women of color and ended prisons altogether.

From inside her prison cell, Candi Raine writes, “The road is long, but the light is so very bright.” The new edition of Captive Genders comes on the heels of the largest survey yet of LGBT prisoners in the United States. Now more than ever, we have information at our fingertips to help us learn how to move toward that light together.

Eric Stanley, one of the editors of Captive Genders, had a chance to answer some of my questions about how they brought this book into being, and what they hope it will do.

Gabriel Arkles: Media attention to trans prison issues has surged in the last few years. What opportunities and dangers do you see in this heightened visibility, and how does Captive Genders fit into the mix?

Eric Stanley: Like many of us, I feel deeply ambivalent about the current moment of hyper visibility. It seems we too often forget that the mainstream media is foundationally anti-Black and transphobic, so its ends can never be anything but that. However, even within these structures, sometimes moments of possibility emerge. The question then, is how might we siphon off some of this attention and the resources it produces and redirect them toward a radical politic. We hope that Captive Genders, along with other accomplices, can hijack our current moment of hyper visibility and the impending turn toward trans liberalism and open paths toward a fabulously collective and liberatory future.

Many of the authors speak powerfully about prison abolition. It seems to me that a lot of the leadership in prison abolitionist movements in recent years has come out of trans and queer communities – even though, as Reina Gossett points out [in the book], radical organizing has often violently exiled trans women and other trans and gender nonconforming people. Why do you think so many trans and queer folks are drawn to this work, despite the legacy of exile?

This is actually one of the reasons Nat Smith, (the book’s other editor) and I first started dreaming of Captive Genders, almost 10 years ago now. This is something I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about, but still don’t have an answer. However, by way of a non-answer, we might argue that this antagonism is illustrative of larger currents in the Left of both inclusion and exile. Our aim with Captive Genders was to move LGBT politics toward a prison abolitionist analysis and also to push the Left to work against their own trans and homophobia. As Reina helps remind us, we often feel disappeared within what on the surface are “our movements.”

Many of the authors point out problems with LGBT communities not taking prison issues seriously. Morgan Bassichis, Alexander Lee and Dean Spade chart how mainstream LGBT “solutions” fall short of what we really need. Yasmin Nair reveals the erasure of state violence in advocacy on LGBT immigration issues. CeCe McDonald makes it clear that many people claim to be activists without taking risks and doing work. How do you hope that trans and queer communities will build, grow and change to meet these challenges?

I still believe in the necessity of collective mass movements in growing our liberation. Yet I don’t think creating coalition can, or should ever be built through silencing parts of ourselves. Hopefully we have at least begun to exorcise the ghosts of a certain kind of Leftist orthodoxy that demanded coherence at the expense of difference.

When McDonald is talking about the importance of doing the work and not just talking the talk she is pointing towards how “social justice activism” trends and recedes. With prison abolition work, as with all our work, I think we must think generationally and not just about the next few months. For example, it’s important if we start writing someone on the inside that we understand the unequal power dynamics in this encounter. I urge people before entering these relationships to think about our own capacity. It can be really harmful for someone to begin a pen pal relationship with someone inside, and then just randomly stop responding. This said, I urge everyone with the capacity to start writing people inside!

Janetta Louise Johnson and Toshio Meronek’s new piece breaks down the lingering impact of incarceration on people who have gotten out, and shares the importance of a disability justice framework for understanding interdependence. The piece from Reina Gossett, Bo Brown and Dylan Rodriguez from the first edition also emphasizes the need to commit to disability justice as an abolitionist process. How do you see the relationship of trans prison abolitionist work to disability justice? Do you think of Captive Genders as being in conversation with the anthology Disability Incarcerated that came out last year?

Yes! Disability Incarcerated is an amazing book that I cannot recommend enough. And like you said Janetta and Toshio’s new piece points directly toward the intersections of disability and abolitionist work, especially through the lens of re-entry. Disability justice communities and PIC [ prison industrial complex] abolitionist communities still have a lot of building to do. One place I hope this work can more intentionally meet is around HIV criminalization. For example the struggle to free Michal Johnson, who was recently give a 30-year sentence under HIV-phobic “exposure” laws, is one place that demands we see the PIC as a matrix of anti-Black, ablest and anti-queer violence. There are of course multiple spaces of contact and co-constitution, but I think working toward the decimalization of HIV positive people and their immediate release from custody is vital.

In your view, what does the second edition of Captive Genders have to offer those people who already read the first edition, and perhaps some of Chelsea Manning’s and CeCe McDonald’s other work? Will they still find exciting new ideas if they get this edition?

I hope all the new pieces help build and expand that radical work that lives in the first edition. I think the new pieces, with their focus on disability justice, settler colonialism and the military industrial complex, push us toward deeper understandings of an abolitionist politics that we need.

In the acknowledgments, you mention that despite a lot of careful work, some “important ideas and voices” are still missing from Captive Genders. What challenges did you encounter in putting together this anthology?

We have always understood Captive Genders as one moment in a long genealogy of anti-prison work. Or, we wanted to acknowledge how it would (like all our work) be an incomplete project. That said, we sent probably 400 calls for writing inside through the Sylvia Rivera Law Project and Critical Resistance. And we ended up publishing all the pieces we got from folks on the inside. We would have loved to include even more work from currently incarcerated people. We got a number of letters in response that talked about how they wanted to contribute but feared they would be punished by the prisons if their work, even if written anonymously, was discovered. This is one of the material realties of writing about prisons from inside them.

We also wanted to open up the category “most impacted.” While we wanted to continue to center people currently inside, we also wanted to include under that banner sex workers who might be arrested and released many times a month. While they might not spend long stretches of time inside, their daily life is mitigated through the prison industrial complex. Along with this expanded understanding, we wanted to include people living in deeply institutionalized spaces, like Ralowe Ampu’s piece about the SRO (single resident occupancy) hotel she lives in.

In her foreword, CeCe McDonald shares thrilling plans to use Captive Genders as a part of an activist training program for people in prison. What else can you tell us about ways people have used or plan to use Captive Genders?

Nat and I decided from the beginning that all the profits we receive from sales of Captive Genders will go to provide free copies to people inside prisons and jails. Through LGBT Books to Prisoners, along with other organizations, we have sent about 500 copies inside so far. This has helped to provide a feedback loop were people inside can respond to the book. The book has also been used in a number of inside/outside study groups, which is really exciting. All this is to say that we see Captive Genders as one part of a large and morphing strategy, which includes reading and writing along with direct action and all other forms of artistic resistance.

Press freedom is under attack

As Trump cracks down on political speech, independent media is increasingly necessary.

Truthout produces reporting you won’t see in the mainstream: journalism from the frontlines of global conflict, interviews with grassroots movement leaders, high-quality legal analysis and more.

Our work is possible thanks to reader support. Help Truthout catalyze change and social justice — make a tax-deductible monthly or one-time donation today.