When Justice Harry Blackmun came to the Supreme Court in May of 1970, he probably expected nothing more than the mundane, cloistered life of a SCOTUS judge. Fourteen years later, on October 11, 1984, guards were doubled at the doors of the court to protect him, and FBI agents were dispatched to investigate a letter threatening his life.

In penning the Roe v. Wade decision eleven years earlier, he had attempted to balance a woman’s reproductive rights with the state’s purported interest in the result of that conception. Though his decision made abortion legal, others insisted he’d violated a higher law. They claimed it neither addressed the morality of abortion, nor the crucial issue of when life begins. These were issues segments of the religious right were willing to violently assert. While on its face this militant wing appears to be driven by a sincere moral imperative in asserting the rights of the fetus over the mother’s, closer examination shows that abortion is for them part of the religious right’s larger agenda – to establish a theocratic state and to supplant secular law with a neo-Calvinist, religious doctrine. To this end, they have employed an artful use of mass media, legislative initiatives, and outright violence in pursuit of this goal.

Like a social thermostat, the virulence of the anti-abortion movement has intensified with every victory in women’s rights, its rage stoked with each instance of female empowerment and self-determination. The philosophical, socio-economic, and psychological forces that have propelled these divergent interests are like a perpetual motion machine, emerging periodically and planting its feet in order to wage cultural war over issues like abortion and school prayer in different scenarios and contexts. It is necessary, therefore, to understand that over the country’s history, the fortunes and fate of these conflicting interests – the women’s movement and organized religion – have advanced along inverse continuums, viewing issues like the role of the family through different lenses. While this gender-driven tension is rooted in an age-old misogyny at the heart of Pauline Christianity in general, it gains relevance at that point where it coalesces around political rivalries, i.e., as organized power centers jockeying for political power.

One might ask: At what point and under what conditions does a member of a group or social movement feel compelled to step outside the established boundaries of peaceful protest and resort to violence? Since there is, of course, no single inducement to such a course of action, a closer look betrays a number of contributing factors.

Blind Quest to Supress Opposition

In terms of the violent anti-abortion movement, it is impossible to consider such behavior in a strictly religious context since the religious impulse itself, ironically and in great part, needs the perceived evil and miscreant behavior of its detractors as a foil to justify its own existence. Though the believer’s fervent commitment to the faith is grounded in fear of the certainty of death, this is only the most fundamental, personal part of the violent believer’s worldview that inspires in them a natural “fight, flight, freeze” reaction. There is a more consequential sociological element in the believer’s distrust, disdain, and even revulsion, for those who do not share their view. It is this component that devolves from a simple benign disrespect for an opposing position, to a blind quest to suppress it at all cost.

While it seems a settled proposition among many authors and philosophers that moral absolutism is elusive and even dangerous, it is, on the contrary, the mother’s milk of religious fundamentalism. Indeed, the fame and adulation heaped upon the murderers of abortion doctors in some quarters of the anti-abortion movement gives a surreal credence to the truth of that proposition. But the religious motive is only the most obvious element in the emergence of the abortion issue to the forefront of political controversy.

There are many pious believers in the world whose hands never touch anything more lethal than a prayer book or beads. Borrowing a notion from Malcom Gladwell, author Dipak Gupta reminds us that what propels abortion or any issue into the limelight are the same rudimentary elements of communication that make products like the iPhone wildly popular.(1) They do not emerge from a vacuum, but come at the confluence of three broad elements: a charismatic and persuasive messenger to tell about it; a compelling message; and a context that causes the product or idea to “stick.” The religious right has successfully exploited this process, causing a minority of its faithful to devolve into violence in the process.

Were the abortion wars merely a theological rift, the battles would be quiet affairs, as mundane and inconsequential as a sectarian dispute over the trinity or transubstantiation. But religion is only the most obvious fault-line abortion follows into the culture. The death and destruction perpetrated by some of its detractors in years past show that abortion’s fissures emerge from a place far deeper than dogma in a pattern too complex to have simply generated from the pulpit. It shows too that faith is not a monolithic and passive force in society; it brings to its conflicts the same psycho-social elements – i.e., sexuality, economics – that motivate its secular counterparts, albeit in different, symbolic guises.

One such symbol running uniformly through the religious camp inspiring revulsion is that of Eve, the archetypal female whose independence and curiosity is to be distrusted and repressed. That our Constitution did not deign to grant women even the rudiments of citizenship indicates that while the founding fathers may not have shared religion’s negative assessment of the female, neither did they challenge it doctrinally. The rights of women, therefore – whether reproductive, civic, or otherwise – were at the very least a source of indifference, if not outright contempt.

Abortion has existed in every culture and will continue to do so. Of itself, the act has little power to attract attention, and, as history shows, women will always want and utilize it no matter what its status in the culture. Like a flame, abortion can be dormant and useful as a pilot light or a raging inferno roaring through the body politic. Whether it is one or the other depends on the fuel, and in the case of abortion, the most volatile accelerants have been the social forces seeking to exploit and suppress it for their own political ends.

As author Bethany Moreton has suggested (2), the spate of anti-abortion and homophobic legislation issuing from conservative statehouses since the ’80s and the reinvigorated culture wars in general are merely dog-whistle palliatives, distractions thrown to a fundamentalist base who otherwise might be alarmed at the toll conservative economics has taken on their jobs and wages in the last 30 years. With the exception of the Catholic Church (whose injunction against it has been absolute and historically consistent), abortion’s reputation has not always been scurrilous. As an issue, abortion is more a matter of political utility than morality.

Moral Status not Inherent

Before the mid-1800s when, ironically, abortion came under attack by doctors (who wanted to neutralize the power of midwives) rather than clerics, its moral temperature in the nascent state was quite tepid. Except for the Catholic’s eternal ban, abortion was like the embarrassing relative one had to claim, but keep hidden from the public. Abortion’s moral status is therefore, not inherent, but is assigned according to other cultural priorities and power struggles. Its acceptance at the time was due less to the influence of political advocates than a simple lack of enemies. This changed in 1848 with the women’s convention at Seneca Falls. It kick-started a women’s suffrage movement that culminated in the formation, in 1869, of the National Association for Woman Suffrage by Susan B. Anthony. Now the threat was real and struck at the bedrock misogyny of Christianity and extant US culture. The war was on, and the enemy was the specter of a liberated, enfranchised woman. Henceforth, the battlelines would be drawn along a gender-based struggle for women’s right to self-determination and an entrenched male culture determined to thwart it.

In 1973, the Roe decision tore open the door to reproductive rights that had been bolted and nailed shut by the Comstock Law a hundred years earlier, the federal legislation that had made birth control and abortion illegal. Up until Roe, orthodox Christianity – both Protestant and Catholic – was able to simply cede to government the suppression of reproductive rights through a combination of codified law and a subtler system of cultural opprobrium. While Roe undid the former, the pill and the effective control of the birth cycle loosened the grip of the latter. With this menacing sexual liberalism nipping at its heels, the Catholic church made its first tentative legislative forays, sending its emissaries to House and Senate hearings in an attempt to stem the cultural tide. Pope Francis VI weighed in in 1968, reasserting the church’s ban on birth control and abortion.

Younger in lineage and less grounded in dogmatic constraints, the dominant Protestant faith was more susceptible to sociopolitical winds and more likely to be moved by them. But the prevalent strain of Protestantism since the American revolution had been pre-millennialism, a passive doctrine that urged its followers to forsake the political realm for the virtuous and purgative power of labor and prayer, waiting patiently for Christ’s second coming.

Except for brief resurgences, the normative power of religion in the United States has been subordinated to the country’s materialistic impulses. Religion was, as Jeffery Hadden has suggested, somehow rendered permanently and politically impotent by commercial and political forces which, if not overtly atheistic, relegated religion to a secondary role.(3) After Roe, however, such complacency was not an option for certain Protestant fundamentalists who deemed any female aspiring to a purpose other than reproduction and husbandry a fallen reprobate. A new theology was needed to confront the twin scourges of birth control and abortion, one that not only countenanced, but demanded the right’s activism in the political arena.

Embracing Religious Government

Despite the increasing secularization of US society, there has always been a small but vigilant cross-section of theocrats who have not only embraced the notion of a religious government, but have felt it their duty to establish one. Such a view hearkens back to the very first colonists who were fleeing not so much political tyranny as an intolerant Catholic religious establishment underwritten by state power. Their mission was nothing less than to create the physical manifestation of God’s dominion in a new land. Hence the name “Dominionism,” which comes from Genesis 1:26-31.

Invoking Calvinist calls for religious dominance in government and the market place, an expatriate American missionary living in Switzerland named Francis Schaeffer redrew the theological blueprint for militant evangelism in 1976. By attributing what he deemed the fallen state of Western civilization to a rejection of the Protestant Reformation for secular humanism, Schaeffer unapologetically proposed the foundation of a Christian theocracy in the United States by any means possible. However, his jeremiads hardly reached beyond the walls of the seminary or clerical roundtables. Schaeffer needed a hot-button issue that would provoke believers on a dramatic, visceral level, combining Christian passion surrounding Eve’s transgression in the garden, the horror of infanticide, and Mammon subverting God’s law. He found it in Roe v Wade. Legalized abortion was the perfect foil.

In 1979, Schaeffer collaborated with his family pediatrician, C. Everett Koop, on a book called Whatever Happened to the Human Race? In a 26-week book tour with seminars and a film with grizzly depictions of abortions, the duo inundated evangelical audiences with the notion that Roe’s legalization of abortion was a new holocaust and the beginning of America’s moral decline.

Anti-abortion activists had already been blockading clinics and harassing incoming patients since the early ’70s, and some local governments began a pattern of burdensome licensing requirements for clinics that continues to this day. But the book and the new activism were just part of the perfect conservative storm that was gathering around the then-impending election of Ronald Reagan in 1980. The movement may have languished were it not for the efforts of direct-mail pioneers Richard Viguerie and Paul Weyrich, who both saw abortion as a touchstone for broader conservative discontent. This confluence of forces was a tipping point in abortion’s rise to become the right’s cause celebre. Firmly balanced on its new conservative political legs, the anti-abortion movement sought to recruit its messengers and exploit this valuable and incendiary message as long as they could.

Media and the Messengers: Making It Stick

Abortion, then, would not have found its way into the center of cultural discourse had it not been thrust there by socio-economic forces quite unrelated to abortion as an actual medical procedure – an act throughout much of history deemed mundane and amoral. It has become a pawn in a larger struggle between theological and secular forces over the role of gender in society and the locus of state power. While one would not suspect that Bruce Hoffman’s notion linking the rise of religious terrorism to the failure of global capitalism in the Third World (4) would apply to the United States, when seen through the lens of the economic toll then being wrought by globalization on the American middle class in the late ’70s and early ’80s, the analogy is quite appropriate.

American males, Susan Faludi also reminds us, were hardest hit by the outsourcing of well-paying manufacturing jobs.(5) More importantly, for the first time in the ’80s, there were 50 percent less men in the workplace and more than 50 percent more women. This triggered, Faludi contends, a male backlash against a feminist movement they blamed for this deficit. But the working-class men actually affected by the cultural change did not give formal expression to the backlash. They were merely the receptors of an anti-feminist message crafted by churchmen and right-wing politicos and disseminated through the echo chamber of mega-churches and a growing evangelical electronic media.

Modern evangelism drives the abortion wars. It began not in the pulpit, but in the revival tent. Old-time revivalists like Charles Finney could only have dreamed of the power and reach afforded modern evangelists like Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson through electronic media. From the beginning, the major obstacle to fundamentalists eager to create God’s kingdom has been a culture of diversity and a truly educated polity hungry for multiple streams of information – a prospect abhorrent to theists for whom moral truth is not a collaborative process of moral realism, but a matter of internalizing the commands of self-appointed religious bloviaters with a microphone. Religious broadcasting has gone a long way toward removing this impediment. Sadly, with this phenomenon also comes a mass of cowed believers locked inside the right-wing Christian echo chamber. In the process, real communication has been replaced with hate-speech and emotional images calculated to inspire fear and unquestioned obedience. More importantly, as Marshal McLuhan surmised, the power of the electronic church resides less in the message, than the electronic media itself.

According to McLuhan, media fall into two basic categories: hot and cold. A hot medium is rich with content, demanding little of the user’s input or intelligence to cull its message. A cold medium, on the other hand, requires the user to interface more or fill-in with his/her own psychic energy and intelligence. As McLuhan sees it, the hot form is exclusive and the cool one inclusive.(6) “Radio and TV are hot mediums. Because they engage the listener on a more visceral and sensory level than the intellectual and reflective act of writing, the elements of the message are richly provided by the medium itself. Consequently, because radio tends to be opaque to the cultural presuppositions of its listeners, it is a very effective medium for supplanting those presuppositions to its own ends.”

As examples, McLuhan invokes Hitler’s propagandistic use of the radio waves as well as, to be fair, Roosevelt’s fireside chats. Most important, however, is the fact that the effect of radio is to “re-tribalize,” to reconnect the listener to the community from which he/she has been alienated by society’s obsession with mechanization and intellectualism fostered by dependence on the visual, phonetic alphabet. Thus, the power of evangelists to fulminate over the airwaves about the evils of abortion and to drive home their message with bloody and graphic pictures of aborted fetuses taps into the same ancient energy that storytellers once used to grip a captive audience around a campfire with tales of Achilles and Odysseus.

Schaeffer had indeed come down from the mountain with a newly politicized theology, but his word alone would not have been enough to coax the Protestant faithful into the streets in militant civil disobedience against legalized abortion and the feminist menace. That was up to his disciples of whom Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson were only the most prominent, by virtue of their vast, electronic pulpits. But even these men were aloof and rarified compared to their loyal believers who blocked clinics, harassed clients and chained themselves to procedure tables.

Like any battle, the abortion wars were fought in the trenches, led by minor functionaries less driven by the cold political calculus of their intellectual mentors than the raw power of the message those leaders had so successfully imbued in them. They were like radios which, locked on the signal from their leaders, could decipher neither the messages from secular law, nor the exhortations from feminists to control their own wombs. The message was clear, and it was sticking. It was another tipping point.

The Crusade: Killing the Baby-Killers

The abortion wars began in the fetal position. Photos of the first full-blown clinic protests in 1975 show not the violent confrontations that would come later, but limp bodies being dragged away by police with no resistance. Some of those photos show Michael O’Keefe, a young Catholic haunted by both the death of his older brother in Vietnam and the specter of his own, self-perceived cowardice.(7) Convinced that all killing, including the unborn, was unjustified, he and his followers adopted a Ghandi-inspired strategy of civil disobedience. Utilizing tactics laid out in a manual for civil disobedience developed by antiwar Quakers, O’Keefe and his followers felt that by passively disrupting the procedures at clinics any way possible short of violence, they could redirect the violence of the abortion procedure onto themselves instead. One very beneficial consequence of this approach was the way it was perceived by legal authorities. Because O’Keefe eschewed violence and because the protests had the veneer of a legitimate public moral stance, the police were reluctant at first to haul them away, and local magistrates often responded with veiled approbation by issuing light sentences. This tactic could only work as long as true, passive resistance prevailed.

Ever cautious lest it jeopardize its business connections and tax-exempt status, the Catholic hierarchy frowned on O’Keefe’s displays. It reminded them too much of liberal antiwar demonstrations. Though the Catholic Church, unlike some Protestants, had no desire to establish a theocratic state (it had had, after all, some rather unsuccessful experience with that), it did know how to nibble at the edges of government. In 1976, it successfully lobbied for the Hyde Amendment prohibiting Medicaid-funded abortions. But the pace of legislative change was much too glacial for the crop of Protestant zealots anxious to establish God’s new order on the tottering edifice of secular society.

O’Keefe’s nonviolent model was simply too passive for zealots eager to bring the fallen world to heel. Their hopes that the Reagan presidency would usher in the demise of Roe were dashed by the tide of Supreme Court decisions in the late ’80s and early ’90s which, though weakening access, preserved a woman’s right to abortion. Disciples of Schaeffer – men like Michael Bray, Randall Terry, and Ralph Reed – insisted the prolife movement had been too nice and respectful.The gloves were off and fists were raised. Ironically, however, it was a Catholic woman who united the two denominations in opposition to abortion.

Notwithstanding the notoriety in 1986 surrounding her arrest and disregard for secular law, Joan Andrews is a case study in the fine line between faith and fanaticism. One of six children born to a Catholic mother in the virulently Protestant Tennessee of the 1950s, Joan was raised in an atmosphere where she was constantly taunted for her faith. The father’s family was Protestant and was contemptuous not only of Elizabeth Andrews’ predisposition to breed, but also her insistence that all the children be raised Catholic. For mother and children, then, Catholicism was less a genuine article of faith than a point of pride to be worn like a chip on the shoulder and defended.

Adhering at first to O’Keefe’s model of passive resistance, Andrews and other protestors became more aggressive when they realized these efforts were not closing down the facilities. They began damaging clinic property. After over 100 arrests, Andrews was finally convicted of third-degree burglary for damaging a Pensacola clinic in 1986. Even in the courtroom, she became the very model of noncooperation, forcing the authorities to carry her everywhere. When she continued this noncompliance in prison, the would-be martyr’s plight was touted in the Protestant evangelical echo chamber, where luminaries like Pat Robertson and Jerry Falwell celebrated her resistance and exploited her situation as a call to arms for the religious right using abortion as a pretense.

Thereafter, with the exception of militants like Joe Scheidler, John Ryan and Shelley Shannon, the Catholic movement was co-opted by Protestant groups like Randall Terry’s “Operation Rescue.” Starting from a shoestring budget in 1986, Terry – a former used car salesman and drug addict – beat the conservative media and mega-church bushes for support until his numbers had grown to thousands of followers willing to overwhelm clinics with sheer numbers, risk arrest and clog the legal system.

Beginning with their first rescue in New Jersey in 1987, their ranks swelled and their tactics became more brazen. But the hubris and recklessness that came with numbers created a downside. Officials were expending great resources and time hauling away and booking thousands of protestors, who, until that point, faced only minimal fines. Judges and police officials tired of the costly revolving door and began imposing buffer zones, serious fines and jail terms. In Pittsburgh, officials began to put liens on the property of protesters who failed to pay. Urged by Terry, thousands flocked to the 1988 Democratic Convention in Atlanta. He’d encouraged them to get arrested and assured them the jails would be too crowded to hold them. Many, however, found themselves in court faced with legal fees and prohibitive fines Operation Rescue would not cover. The cost of protesting was becoming, for many, prohibitive, and many started to sour on the notion of mass civil disobedience.

By the early 1990s, the law was working, and not in favor of Operation Rescue and similar groups whose blockade strategy had been foiled by law enforcement and judicial rebuke. However, though God’s army had been disbanded, many were too emotionally invested in the movement to leave the field of battle. The sermons from the pulpit and the bloody images of abortions had so seized that part of their consciousness where reason does not rule that each fetus represented, perhaps, an extension of themselves and their own insecurity and mortality. Therefore, stopping each abortion was not a matter of mere conviction; each abortion was an existential crisis implying their own metaphoric destruction, something indifferent to politics or the ballot box. Framed within that context, the thought of each abortion triggered in many of these protesters an overwhelming anxiety that could only be resolved through an imagined, unwavering communion with the divine. With this divine mandate comes divine license, and the force that has the power to absorb the pain of drug addiction for someone like Randall Terry and Paul Hill, or to assuage the lack of self-worth for someone like attempted murderer Shelley Shannon also compels them to use any means in service of that power and defense of the fetus – even murder.

Viewing the Battlefield

In hindsight, one wonders what anti-abortion terrorists accomplished by harassing patrons, gluing locks, cementing sewer lines and destroying property other than instilling fear in patrons and employees. Certainly, rogue bombers and murderers like Shelley Shannon, Michael Griffin and Paul Hill did nothing other than ensure their own incarceration and/or execution. There is a theory, whose proponents include Harvard’s venerable Laurence Tribe, that the worst anti-abortion violence ensued as a response to draconian restrictions. Buffer zones, stiff fines and use of pain compliance techniques, it argues, served to stifle mass civil disobedience that was as a safety valve for potential violence (8) during the heyday of the demonstrations. A more troubling aspect of the argument is, however, that Roe had erred in guaranteeing universally the right to an abortion, and that the decision co-opted cultural dialogue already underway in state legislatures.

First of all, the argument is tendentious by creating a false dichotomy with regard to terrorism. By diminishing the ugly nature of the mass demonstrations -characterizing them as simply a benign period bracketed by more violent events like bombings and shootings – it diminishes the very real terror felt by employees and patrons who experienced the onslaught. Secondly, the notion that a woman’s right to choose is somehow a parochial decision for state legislatures is as insulting as implying that civil rights is a states’ rights issue.

Roe is still the law of land; on paper at least. Yet, something has indeed occurred to limit access to abortion, something that serves the goal of a theocratic state and has nothing to do with terrorism. In 1982 there were 2,908 abortion providers. By 2008, they had declined to 1,793. By January 2013 there remained only 734 abortion providers nationally. This has come about not by hordes descending on clinics or burning them down, but by right-wing legislative initiatives on the state level. Forty-five states now have burdensome restrictions like TRAP laws (Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers) and restrictive admitting privileges for physicians providing abortions.

The abortion wars are emblematic of deeper seismic shifts in cultural power. While the surface has roiled throughout with violence and mayhem, the epicenter of the conflict has been, and always will be, government and who controls it. Since the Tea Party ascendance in 2010, the momentum seems to be trending with the fundamentalist right as they take greater bites of the more rational GOP electorate. However, a look at regional demographics shows their victory may be pyrrhic, and their policies may be fostering a need for the reproductive options they so revile.

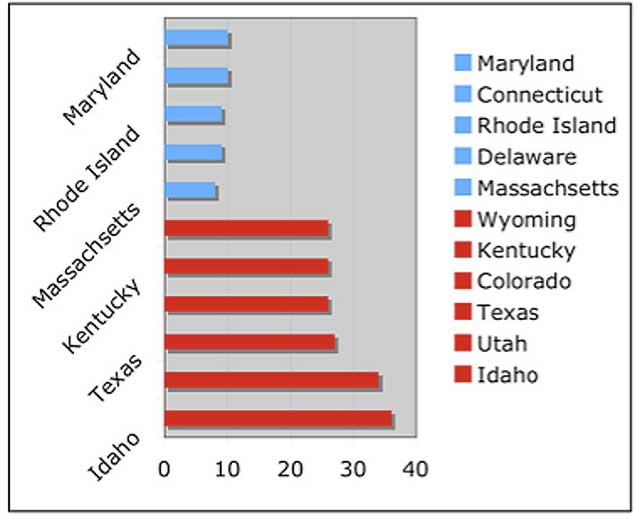

Sadly, statistics show the victims of the abortion wars are its soldiers – especially young women. Many of the fecund faithful who dutifully rage at birth control and clinical abortions are unwitting architects of their own second-class status by their allegiance to fundamentalist Christianity. The culture of abstinence and shotgun marriages creates a pattern wherein people marry younger, are forced early into low-wage work and are precluded by family commitments from pursuing the higher education that might afford them higher earning power. The chart below – from a 2006 book by Naomi Cahn and June Carbone (9) – illustrates demographically (states listed in order on the right), in percentages, the disparity in the number of teen couples burdened with children in conservative states as opposed to more liberal ones, where birth control and abortion are more readily available.

For many men in this culture, economic stress coupled with the fear of emasculation by women in successful roles often compels them to seek a scapegoat and to externalize their anger at a society they perceive as failing them. They thereby become perfect repositories for the misogynistic rhetoric of fundamentalist preachers who tell them the source of their problem is women who, instead of staying home to take care of them and their children, want to kill their babies so they can go off and have careers. Such a message in an already frustrated and disordered mind can incite them to violence and murder.

Finally, considering the right’s success in capturing state houses, the ever-rightward tilt of Congress, SCOTUS’ recent Hobby Lobby decisions regarding contraception, and their ruling on buffer zones, prochoice activists must feel like Roe is as vulnerable as a wildebeest at a watering hole. Indeed, the lions of the right would certainly like to devour it. Were that the case, then the religious right’s ascendance would bring another tipping point not just for abortion, but for the very nature of governance in the United States.

Though terrorism may not have played the definitive role in the de facto suppression of abortion, the fear, destruction and murder it did inspire is only half-heartedly rebuked by leaders of the right, who feign outrage, yet applaud it in private. It is hard to imagine that so effective a tool would simply be disavowed by a party who has profited from its success. In the case of abortion in the United States, theological terrorism – through co-opted government – will not come at the point of a gun, but in the cold compulsion of the law that will push women once again back into dirty rooms where the inept and careless wait with crude implements and noxious concoctions. It will of course be done in the name of God, for terror in the name of the Lord, they claim, is not terror at all.

Notes:

1. Gupta, Dipak K. Perspectives on Terrorism/Accounting For the Waves of International Terrorism. In Terrorism and Homeland Security. 3. 2005.

2. Moreton, Bethany. Why Is “There So Much Sex in Christian Conservatism and Why Do So Few Historians Care Anything about It?” Journal of Southern History. 75.3 (2009): 718. Print.

3. Hadden, Jeffery K. “Religious Broadcasting and the Mobilization of the New Christian Right,” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 26.1 (1987): 1.

4. Hoffman, Bruce. Inside Terrorism 1st. New York: Columbia University Press, 2006. p. 86.

5. Faludi, Susan. Backlash/The Undeclared War Against American Women. 1st. New York: Anchor Books/Doubleday, 1991. p. 48.

6. McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media/The Extensions of Man. 2nd. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994. p. 23.

7. Risen, Jim/Thomas, Judy L. The Wrath of Angels/The American Abortion Wars. 1st. New York: Perseus, 1998. p. 58.

8. “Safety Valve Closed: The Removal of Nonviolent Outlets for Dissent and the Onset of Anti-Abortion Violence,” Harvard Law Review. 113.5 (Mar. 2000): p. 1211.

9. Cahn, Naomi, and Carbone, June. Red Families v. Blue Families/Legal Polarization and the Creation of Culture. 1st. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $31,000 in the next 48 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.