Support justice-driven, accurate and transparent news — make a quick donation to Truthout today!

The US government agency responsible for interstate pipelines recorded a catalog of problems with the construction of TransCanada’s Keystone Pipeline and the Cushing Extension, a DeSmog investigation has found.

Inspectors at the US Department of Transportation’s Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) observed TransCanada’s contractors violating construction design codes established to ensure a pipeline’s safety, according to inspection reports released to DeSmog under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA).

Evan Vokes, former TransCanada materials engineer-turned-whistleblower, told DeSmog the problems uncovered in the reports show issues that could lead to future pipeline failures and might also explain some of the failures the pipeline had already suffered.

Vokes claimed PHMSA was negligent in failing to use its powers to shut down construction of the pipeline when inspectors found contractors doing work incorrectly. “You cannot have a safe pipeline without code compliance,” Vokes said.

The Keystone and the Cushing Extension are part of TransCanada’s Keystone Pipeline network, giving the company a path to move diluted Canadian tar sands, also known as dilbit, to the U.S. Gulf Coast.

The Keystone pipeline network is made up of the Keystone Pipeline (Phase I), that runs from Hardistry, Alberta, to Steele City, Nebraska, and the Keystone-Cushing extension (Phase ll), from Steele City to Cushing, Oklahoma. There, it connects to the southern route of the Keystone XL, renamed the Gulf Coast Extension (Phase III), that runs from Cushing, Oklahoma to the Gulf Coast in Texas.

The final phase of TransCanada’s network, the Keystone XL, (Phase lV), originating in Alberta, is meant to connect to the Gulf Coast pipeline. But KXL is blocked for now since President Obama rejected a permit TransCanada needs to finish its network.

According to the inspection reports PHMSA provided, its inspectors observed TransCanada violating construction design codes established to assure a pipeline’s safety. Inspectors wrote that some contractors working on the Keystone were not familiar with the construction specifications.

The reports show that when PHMSA inspectors found improper work, they explained the correct procedures — such as telling welders the correct temperature and speed they needed to weld at according to specifications.

In one instance, a PHMSA inspector found a coating inspector using an improperly calibrated tool, so the PHMSA representative instructed him on the proper setting.

The inspection reports also describe regulators identifying visible problems with pipe sections as they were placed in ditches, and of ditches not properly prepared to receive the pipe.

PHMSA inspection report of the Keystone pipeline 6/15/2009 to 6/19/2009.

PHMSA inspection report of the Keystone pipeline 6/15/2009 to 6/19/2009.

“Regulators did nothing to stop TransCanada from building a pipeline that was bound to fail,” Vokes told DeSmog after reviewing the construction inspection reports for the Keystone 1 pipeline and the Cushing Extension.

According to Vokes, those welders and inspectors should have been fired because problems with welds and coatings can lead to slow and hard to detect leaks.

“It is impossible to believe the welders and inspectors cited in the PHMSA reports were operator qualified, which is a mandated requirement by PHMSA,” Vokes said.

TransCanada insists it used qualified contractors.

Matthew John, a communications specialist for TransCanada, told DeSmog: “In fact, the Special Permit conditions for Keystone Phase 1 and the Cushing Extension included a requirement for TransCanada to implement a Construction ‘Operator Qualification’ program. We only use highly trained and specially certified contractors in the construction of the Keystone System.”

But the PHMSA inspection reports cast doubt on the effectiveness of the ‘Operator Qualification’ program.

Vokes said: “How is it possible that PHMSA could find multiple violations at multiple sites on multiple days in multiple years?”

“It isn’t a regulator’s job to instruct contractors how to comply to code,” Vokes said.

“If the construction crew was not familiar with the correct procedures, they shouldn’t have been allowed to continue constructing the pipeline.”

Part of Vokes’s job as a pipeline materials engineer was to ensure TransCanada adhered to the accepted codes of pipeline construction set by institutions such as the American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

“Straying from the adopted code is not only illegal, but it compromises the integrity of a pipeline,” he said.

Vokes says that during his five years with the company he did his best to get TransCanada to identify and solve its problems. But he said the company continued to emphasize cost and speed rather than compliance.

This compelled Vokes to send damning evidence of code violations to the Association of Professional Engineers and Geoscientists of Alberta, the Canadian National Energy Board, and PHMSA.

He was fired after airing TransCanada’s failures, which did not surprise him. He is, however, surprised regulators in the U.S. and Canada continue to let TransCanada and other companies build pipelines that are not built to safety standards.

Vokes told DeSmog he had sent senior PHMSA investigator Gery Bauman a “binder full of information” showing issues with TransCanada’s construction methods. “Bauman seemed concerned and told me that he would look into my allegations, but blew me off.” According to Vokes, Bauman stopped responding to his emails.

PHMSA confirmed it received documents Vokes sent to Bauman and reviewed them. Bauman and other communication specialists at PHMSA were asked by DeSmog to comment on the communications with Vokes, but have not responded.

According to Vokes, the documents he gave Bauman contained proof that TransCanada didn’t follow minimum safety standards when building the Luddem pumping station — the same pump station that spilled about 400 gallons of oil in North Dakota in 2011.

Bauman witnessed some of the construction problems firsthand. An inspection report on the construction of the Keystone Pipeline bearing his name, dated 06/15/2009 to 06/19/2009, states:

“G. Bauman and M. Kieba conducted an inspection of Spread 3B out of Aberdeen, SD. The issues and concerns noted by Gery ranged from coating anomalies not being repaired to bolts causing coating damage. Additionally, a joint of pipe was found with a three-inch section where the wall of the pipe was measured to be 0.356″. Gery also inquired about the CP [cathodic protection] of the line that had been in the ground for almost a year, and line markers to help prevent any possible third party damage.”

Vokes believes the problems Bauman described could lead to a spill. He explained regulators should have required an integrity test to determine if a sleeve (protective layer) was required, but the report makes no mention whether such a test was ordered.

DeSmog asked Bauman and the PHMSA if the issues Bauman reported on Spread 3B could lead to a spill and an integrity test or any other kind of follow-up work was ordered, but did not receive a reply.

Bauman warned Kinder Morgan, another pipeline industry giant, on similar “inappropriate” construction practices when he inspected REX, a natural gas pipeline that runs from Colorado to Pennsylvania completed in 2009. PHMSA accepted assurances form Kinder Morgan that remedial actions would be taken. But whatever actions Kinder Morgan took, they did not prevent a gas leak causing evacuation of nearby homes in southeastern Ohio or a slew of other incidents.

After reviewing the construction inspection reports obtained by DeSmog on the Keystone and the Cushing Extension, Vokes said that regulators cite numerous problems grave enough that, in his opinion, PHMSA should have shut the project down. He said PHMSA’s apparent acceptance that operators would change their ways showed the agency learned nothing from REX.

Another PHMSA inspection report, dated June 2009, indicates TransCanada ignored basic protocols by working on the Keystone pipeline without written specifications. “That gave PHMSA grounds to shut the work down on the spot,” Vokes said.

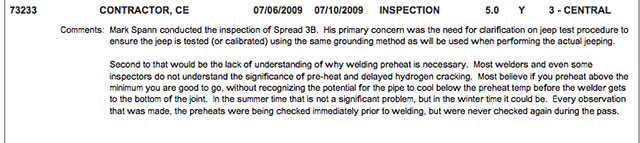

PHMSA inspection report 7/06/2009 to 7/10/2009 indicating multiple regulation violations by a third-party auditor.

PHMSA inspection report 7/06/2009 to 7/10/2009 indicating multiple regulation violations by a third-party auditor.

“The PHMSA inspection report dated 10/05/2009 to 10/09/2009 foretells the kind of leak that led to the spill from a section of Keystone Pipeline in South Dakota,” Vokes said. The spill, discovered on 2 April, leaked an estimated 16,800 gallons of dilbit because of a faulty transition weld.

The report states: “There has been a problem with cracked welds on this spread, which is well known to the personnel involved. The problem got worse with twenty cracks the last seven working days. The mainline welded out on Wednesday, October 7, 2009.”

The PHMSA inspection report dated 08/24/2009 to 08/28/2009 calls out a coating inspector for using an unauthorized tool, stating: “The procedures call for a utility knife of a specific size to be used for performing the coating V notch adhesion test. The coating inspector used a lock blade knife for the inspection.”

“Why not just use a pocket knife or prison shank while the coating inspector is at it?” Vokes joked.

Though PHMSA chose not to fine TransCanada for any code violations during construction of the Keystone and Cushing Extension phases after the Keystone Pipeline became operational, PHMSA fined the company twice for construction violations following incidents that required the Keystone pipeline to be shut down for repair.

This included the spill at the Luddem pump station in 2011 and an extreme corrosion event that was detected in multiple spots in 2012 as well as other probable violations.

Most recently, following the South Dakota spill, PHMSA issued a Corrective Order Notice to TransCanada.

“These actions don’t change the fact that any pipeline not built to code is an accident waiting to happen,” Vokes said.

For regulators to allow companies like TransCanada to break the rules seems criminal to him. “It goes against the code of ethics licensed engineers take that require them to put the safety of people and the environment first,” he said.

Inside Climate News reported that Jeffrey Wiese, a top PHMSA administrator, informed a group of industry insiders that PHMSA has “very few tools to work with” in enforcing safety rules.

But PHMSA does have the power to shut a job site down, to fine operators and require additional integrity tests if regulators have reason to doubt a pipeline’s safety.

A PHMSA public affairs specialist told DeSmog: “PHMSA can refer any discovery of possible criminal activity to either the Department’s Office of the Inspector General or the Department of Justice for further investigation and action. Those agencies may initiate criminal investigations and prosecution as a result of, or separate from a PHMSA referral.”

DeSmog asked PHMSA why inspectors did not shut down construction work or fine TransCanada for breaking rules on the Keystone Pipeline and Cushing Extension projects. PHMSA has not responded.

Despite problems with the Keystone Pipeline prior to the 2 April spill, TransCanada’s CEO Russ Girling boasted about the Keystone Pipeline network’s safety last year on the occasion of the company transporting its billionth barrel of Canadian and U.S. crude oil from Canada to the Gulf Coast.

TransCanada spokesperson John said: “Any deficiencies in code compliance identified during the construction of the pipeline were addressed prior to it being put into service. The Keystone System is safe and TransCanada has one of the best operating records in the entire industry.”

But Vokes asked about the violations that inspectors didn’t catch. “If a pipeline is not built to code,” Vokes insists, “it’s not ifthe pipeline will spill, it is when.”

DeSmog asked PHMSA for final evaluation reports on the Keystone Pipeline and the Cushing Extension after reviewing a Final Evaluation Report for the Gulf Coast Pipeline obtained through a FOIA request.

But PHMSA claims no such reports were conducted for the other two pipelines. Background information provided to DeSmog by the agency indicates that different regions do different kinds of paperwork, which might explain why no final evaluation reports exist for these pipelines.

PHMSA did not quantify what percentage of the inspection reports conducted on the two pipelines it provided to DeSmog.

“It is hard to believe some kind of final inspection report was not done for those pipelines. The Keystone Pipeline was the largest pipeline project in the United States at that time,” Vokes said.

The agency’s website states: “PHMSA inspects pipeline construction to assure compliance with these requirements. Inspectors review operator-prepared construction procedures to verify that they conform to regulatory requirements. Inspectors then observe construction activities in the field to assure that they are conducted in accordance with the procedures.”

The newly released PHMSA inspection reports, minus a final evaluation report, raise further questions about the integrity of the Keystone Pipeline and the Cushing Extension.

Holding Trump accountable for his illegal war on Iran

The devastating American and Israeli attacks have killed hundreds of Iranians, and the death toll continues to rise.

As independent media, what we do next matters a lot. It’s up to us to report the truth, demand accountability, and reckon with the consequences of U.S. militarism at this cataclysmic historical moment.

Trump may be an authoritarian, but he is not entirely invulnerable, nor are the elected officials who have given him pass after pass. We cannot let him believe for a second longer that he can get away with something this wildly illegal or recklessly dangerous without accountability.

We ask for your support as we carry out our media resistance to unchecked militarism. Please make a tax-deductible one-time or monthly donation to Truthout.