[People] don’t know how humiliating and demeaning that little box is, and you’re viewed once you check that box. I’ve been fired because I didn’t put down the homicide I was involved in at the age of 15. And honestly, I felt like shit. I wanted to make-it, I was working hard to be successful on the outside. I walked to work every day, I was getting there on time and doing my job. [My supervisor] called me in, and I knew what it was, I thought I was gonna get a chance to explain and they were like ‘Nah, you never put it down so you gotta go.’ The bottom line is that I was embarrassed to put things down and I got punished for it. But what alternative did I have? So there I was again, in the same defeated position. When I got paid, I was like fuck it, I’m already … just drink. I can’t get a job. But I don’t want that, this crap has to end, you’re labeled for life, there has to be some type of reprieve. There has to be. — Lyle

Stories are a powerful mechanism for social change; entire nations are built and maintained by stories and sharing stories is a way of building community, of shaping identity and constructing meaning. However, the stories and voices of people directly impacted by the criminal punishment system, are routinely excluded from policy and reform efforts. This exclusion is the opening to create alternative sites to bridge understanding, knowledge production and impact public and penal policy.

People who have conviction histories frequently lose control over their own story- the story about who they are, where they have been, what they deserve is interpreted through their rap sheet. Their story begins and ends with their entrance into the criminal punishment system. In the process, people are reduced to one-dimensional characters — “inmate,” “offender,” “felon”— monsters who deserve permanent banishment.

American Friends Service Committee’s Reframing Justice Project is a multimedia storytelling initiative with incarcerated, formerly incarcerated, convicted people and their loved ones. We are using video, photo-essay, short essay and live storytelling. The stories collected from a specialized body of knowledge about the state of Arizona, justice, unfreedom and the afterlife of the criminal punishment system on individuals, families and communities. The goal of Reframing Justice is twofold 1.) Influence public discourse around incarceration issues and 2.) Develop a cadre of leaders who can lead a movement against mass incarceration.

The project began by reflecting on the role of story in the judicial system and the idea of legitimacy. We asked, “Who gets to tell what stories, to whom, and under what conditions about the criminal punishment system in Arizona?” The result is stories that challenge the normativity of the narrative of justice as punishment and redirects the story to center justice as radical love and connectedness.

The stories of people who have been system involved are a tremendous resource. Society frequently forgets data, but rarely forgets the human face behind the story. Kini’s Story, the first video in this series, touches on many of the common pathways into the criminal punishment system for women.

Kini’s Video Story

Reframing Justice from Creative Narrations on Vimeo.

Kini’s story illustrates the devastating impact of social marginalization and abandonment. Certain populations- namely poor, people of color, mentally ill, substance addicted, and children suffering from parental incarceration- are not readily viewed as “victims” even though they may well be, and as a result they are excluded from services that could disrupt the incarceration cycle.

Our first photo-essay, “What No One Wants to Hear,” by Michele Keller, draws attention to the challenges facing people returning to their communities post-incarceration. Her essay highlights the importance of support networks, treatment, and education for returning community members.

What No One Wants to Hear

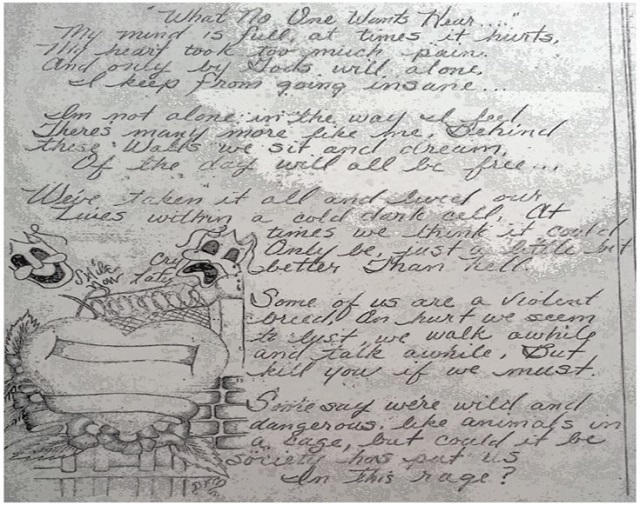

While I was incarcerated at Marana State Prison, another inmate gave me a poem she wrote called “What No One Wants to Hear.” It’s a pretty heavy poem- it captures a lot of the emotion of being incarcerated- anger, sadness, isolation, and inhumanity. I had been in and out of the system starting at the age of 26, each time as a consequence of my addiction to cocaine and crack. When I first read the poem I felt its truth. It illustrates how we feel as formerly incarcerated people as we try to enter back into society, and describes how others see us.

Poem: “What No One Wants to Hear”

Poem: “What No One Wants to Hear”

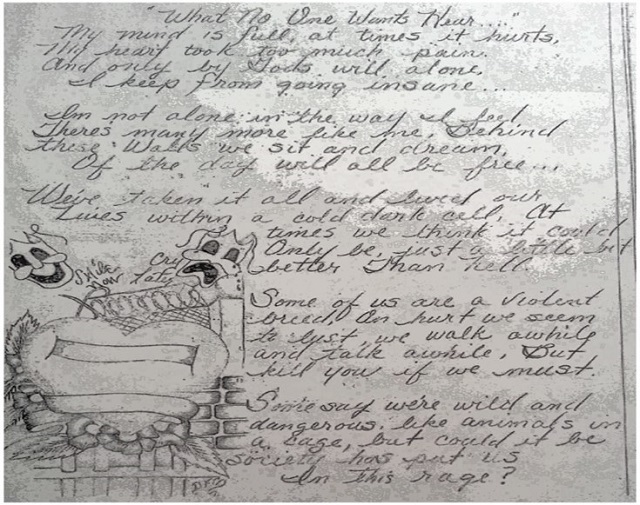

When I got out this last time, what I found most challenging was that I had no family support. My mom had passed away in 2004, which was my breaking point in life. I say “her death brought me life” because her death helped me to pursue sobriety. For a long time, my life in Arizona was about doing/selling drugs.

Michele and her mother, Shirley.

Michele and her mother, Shirley.

I say “her death brought me life” because her death helped me to pursue sobriety. For a long time, my life in Arizona was about doing/selling drugs. That was actually a barrier to reentry for me- I didn’t have a community of support to return to when I got out. Ultimately, what helped me overcome and rebuild my life was the support and resources I gained from the counselors in the Women in Recovery program I attended at Southern Arizona Correctional Release Center (SACRC), which no longer exists.

Video Story: SACRC

Reframing Justice: Southern Arizona Correctional Release Center- Tucson, AZ. from grace gamez on Vimeo.

Now I work as a Behavioral Health Tech and Senior Instructional Specialist. In my work, I am able to make a difference in the lives of people who are struggling with issues that are familiar to those I have been through myself. I feel fortunate to be able to make a positive impact in people’s lives. My life is different now, I am sober, I have gone to school, I own my own home, and my own car. My daughter is excelling at a great school — these are all things that make me proud. However, even though I’ve been out nine years I still sometimes get judged because of my past.

Michele’s new home.

Michele’s new home.

Michele and her youngest child.While inside, much of the time you are referred to by your prison number, which makes it easy to lose your sense of self. I’ve held on to this poem for all of these years because it reminds me of how I don’t want to be seen as a “number.”

Michele and her youngest child.While inside, much of the time you are referred to by your prison number, which makes it easy to lose your sense of self. I’ve held on to this poem for all of these years because it reminds me of how I don’t want to be seen as a “number.”

The poem reminds me not to judge others because of their past poor choices. It helps me remember where I have been, and what I don’t want to go back to. It reminds me that I am blessed to have gotten to the place I am at today. Because of my experiences I am committed to doing everything I can do to help others in their journey to recovery.

***

Ultimately, the stories in the Reframing Justice Project force us to think deeply about what “justice” means and to consider a human justice system that deals with the complex and fragile social problems that lead people into the criminal legal system.

For more information about AFSC’s Reframing Justice Project, and other work on issues of mass incarceration, please visit www.afscarizona.org/reframing-justice/.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. We have hours left to raise the $12,0000 still needed to ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.