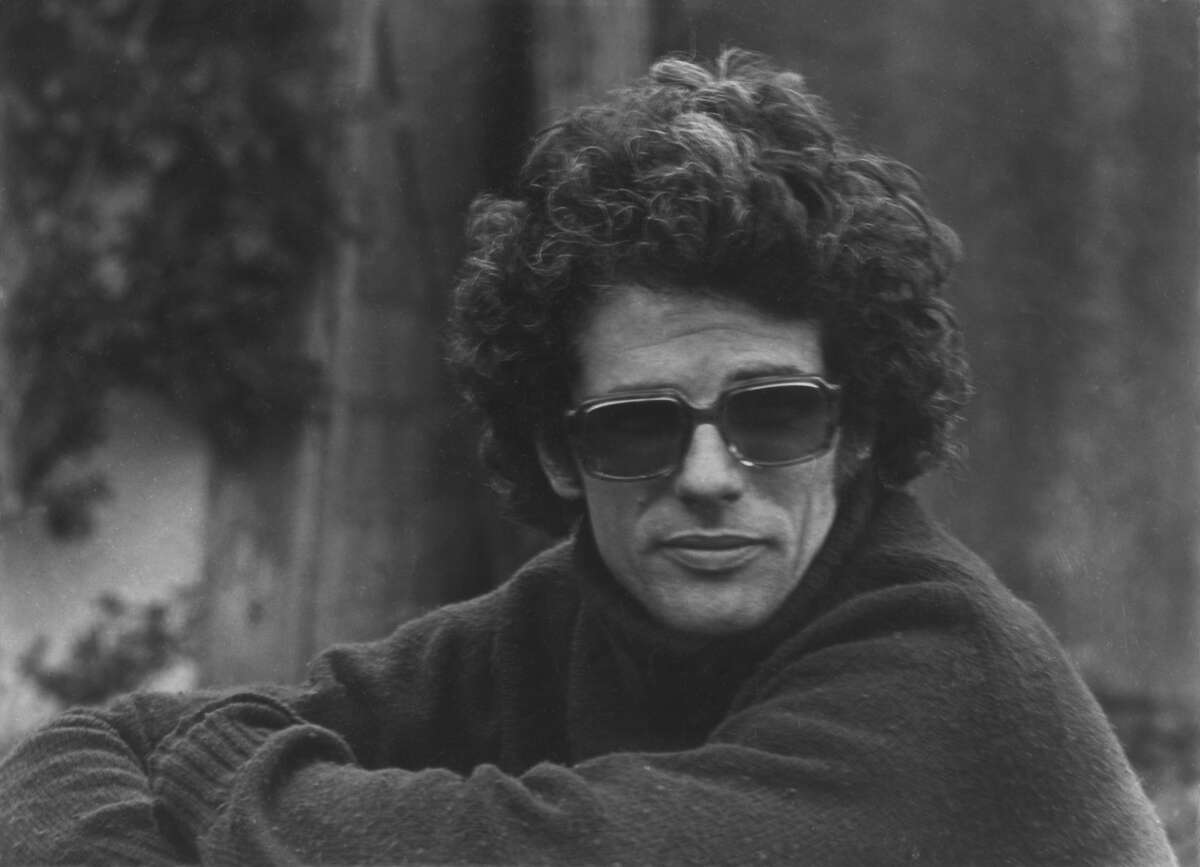

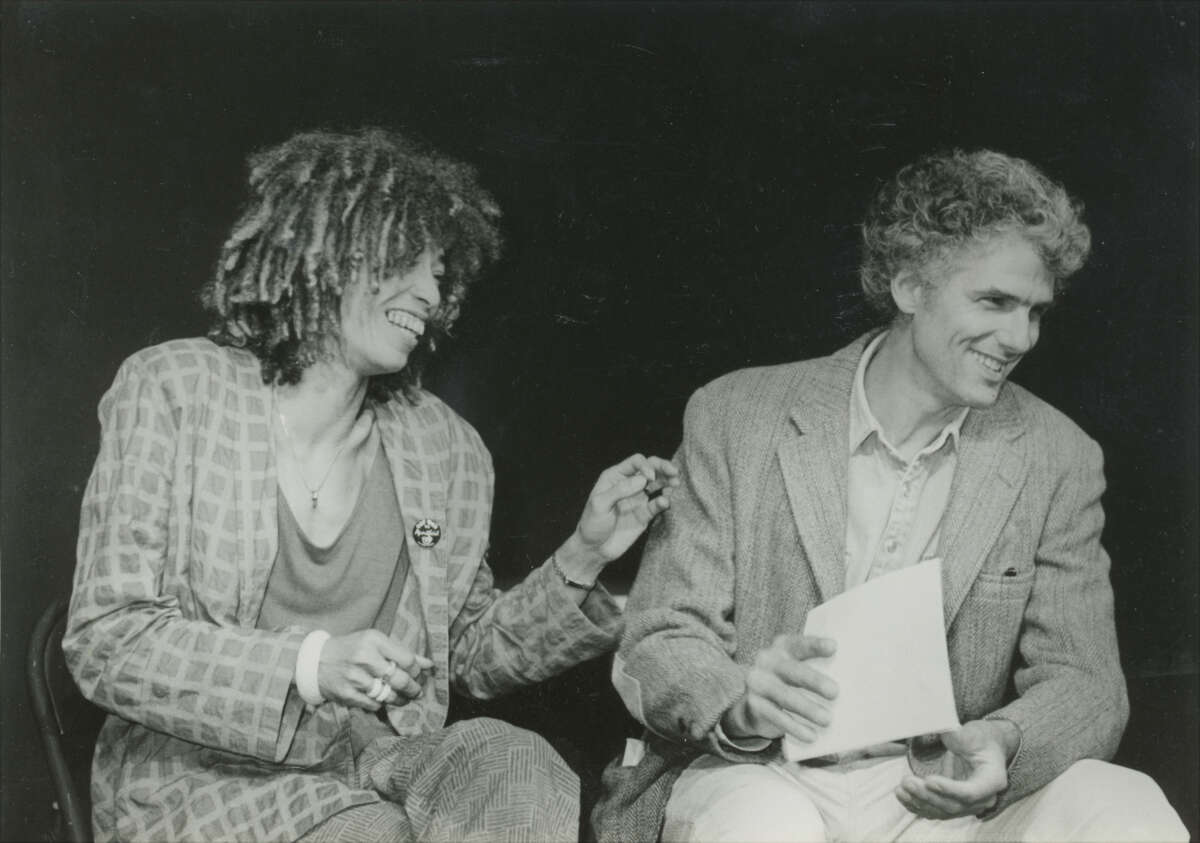

Catherine Masud’s 84-minute documentary, A Double Life, chronicles the journey of Stephen Bingham, the radical attorney accused of passing a gun to incarcerated Black Panther Party member George Jackson that allegedly triggered a shootout at San Quentin State Prison in 1971 and ended in Jackson’s death along with the deaths of five others. Jackson was serving what he called the longest prison sentence ever in California history for stealing $70 from a gas station. The film also examines legendary Black revolutionary icons including author, academic and activist Angela Davis, who was involved with the George Jackson Defense Committee and met George Jackson in prison.

After the August 21, 1971, bloodbath at San Quentin, fearing for his life, Bingham went underground and fled to Europe, where he assumed a false identity and lived using a pseudonym for 13 years. Bingham voluntarily returned to the U.S. on July 9, 1984, to stand trial on two counts of murder and one of conspiracy. On June 28, 1986, a Marin County jury unanimously acquitted Bingham of all charges.

In this exclusive interview with Truthout, Stephen Bingham discusses his role in Jackson’s case, his time living underground in Europe and his own filmmaking experience. The interview that follows has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

Ed Rampell: What was your relationship with George Jackson and what happened at San Quentin Prison on August 21, 1971?

Stephen Bingham: George was interested in filing a civil suit about prison conditions in San Quentin’s euphemistically named “Adjustment Center,” where prisoners were held 23-and-a-half hours a day [in solitary confinement]. My early visits with George were to talk about these conditions. On August 21, 1971, I was requested to accompany Vanita Anderson [an investigator in the Soledad Brothers murder trial in which George Jackson and two other prisoners were charged with murdering a prison guard at Soledad Prison in 1970], to San Quentin to ensure she could visit with George to go over the final galleys of his second book, Blood in My Eye. The authorities had been clamping down on George’s incredible number of visitors. Sure enough… her visit was denied.

She asked if I could take in the materials for him to review, and I agreed to do that. As I was going in with the papers to the attorney’s visiting room off the main visiting room, the guard asked me, “Aren’t you going to take the tape recorder?” I had no need to, so Vanita said I could take the tape recorder.

That’s a key piece of evidence, of course, as the authorities’ whole theory of what happened [the ensuing shootout] is that a gun was inside that tape recorder. There was also a wig, and I had carried all that in to be used by Jackson for some kind of escape attempt. Which of course is nonsense, given the high wall, and the Adjustment Center is a maximum-security prison within a maximum-security prison. So, escaping from San Quentin then and now is virtually impossible. But that was their theory.

I took the papers in, George made some notes, I brought them out and gave them to Vanita and went to have a late lunch with my uncle. I got home around 10:30 and the San Quentin shootout was all over the news. About 20 lawyer friends were waiting for me to arrive, because the National Lawyers Guild was targeted by the FBI; the consensus was I had to immediately disappear.

How’d you get away?

I went to a nearby house hoping the authorities would announce a complete investigation into what happened, but that never happened. From the first hours they targeted me, which fit in with a pattern of targeting movement lawyers. I made a decision, with the consensus of radical lawyers, that I needed to disappear because my life was in danger. If I’d felt I wasn’t likely to get killed I would have stayed and taken my chances. But having been accused of mass killing that included three guards, I was convinced I would not survive if I was in custody. Friends helped me disguise myself. I went to Philadelphia.

Fearing for your life, you fled the U.S. and started to live what the new documentary calls “a double life.”

I got a passport in another name, went to Eastern Europe [which didn’t have extradition treaties with the U.S.] within 10 days after August 21. The governments were aware of the presence of Robert Boarts (my pseudonym), but not of Stephen Bingham. They very much wanted to have U.S. dollars and encouraged tourists with a favorable tourist exchange rate. Prague is an incredible city. I came to Italy in ’72, ’73, and spent almost a year there, working illegally. In June ’74, I moved to Paris.

Why did you live in France for about 10 years?

I had a sense that if I was going to be living somewhere underground for a long time it had to be a very big city. My high school French was better than my German, and if I moved to London, I was afraid of running into people I knew. The French had been receiving exiles and people living underground for hundreds of years.

Describe your “double life” living underground in Paris under an assumed name.

By the time I got to Paris I was fully comfortable with the story I’d created around my name. I never said or heard my [real] name, I really became Robert Boarts, with an inner shell that preserved who I was and my political commitment to work for change. Which is why I got into documentary filmmaking, as well as house painting, which corresponded to my politics of the working class and wanting to identify with them. Instead of just marking off time until I returned home, I wanted my life to be meaningful while I was living in Paris. I think it was — I met [my wife] Françoise.

What was your impression of the French left versus the American left?

One thing that was starkly different that I was impressed with is that in major elections, every credible party is entitled to their time on national TV. I became interested in a Marxist-Leninist political party — I was never interested in the Communist Party, which I found conservative. They supported what the Russians did in Czechoslovakia. In France, the strongest party on the left were Trotskyists, and … they would get their candidate, Arlette Laguiller, eight minutes on national television to say what her program was. There was a sense of the national exchange of ideas, there was a continuum from the far right to the far left, and there weren’t these huge doors the two parties in America close off to anything that’s not one of them. France has a different electoral system, proportional representation, that depending on the percentage of votes you get, parties get X seats in parliament. So, even if the Green Party only gets 5 percent, they might get a couple of seats. I found France’s whole political structure and debate much richer. Our two-party system is not democratic, it stultifies — like none of us, right now, want to vote for Biden or Trump.

How did gauchiste veterans of the French May ’68 student-worker uprising assist you?

Nobody knew I was underground; after I’d been with her for a year, the only person who knew was Françoise. Nobody was assisting me; I was just Robert Boarts, who happened to be a lefty, got involved in film work and went to demonstrations like everybody else on the left.

Tell us about your left-wing documentaries.

I studied at the film school of the University of Paris. I joined Front Paysan, a collective making films for small farmers, who were constantly being screwed by the system and turned into radicals. I wanted to make a film on my own [around] ’80, about this extraordinary battle in a small town, Longwy, which is also the film’s name. It’s a steel town, the heart of Alsace-Lorraine and Europe’s steel industry, and the struggle was over a steel mill that was going to be shut down.

There’s a much stronger identification with unions in France than there is in this country. In Longwy, CGT, the union organized by the Communist Party, was not as aggressive and radical as CFDT, which had more of an association with the Socialist Party. They did these incredible “fist in the face” actions, like a forklift full of wine crashing into the police station. Everybody was talking about that battle at the time, all over the country. I was particularly interested in the dynamic between the different unions that were trying to work together, but it wasn’t working very well. These 16mm films were meant to be used as organizing tools for their struggles — not for the festivals and big theaters.

Why, after 13 years living underground abroad, did you voluntarily return to the U.S. to face charges on July 9, 1984?

All this time I’m away I know I’m going to go back — the only question is when. The only way I could convince people I didn’t do what I was charged with was to come back and have a trial. The presumption was that I had provided George Jackson a gun. Folks I was in touch with paid attention to the San Quentin Six trial [prisoners charged in connection to the August 21, 1971 events]; it did not go all that well for the prosecution.

My mother died while I was away; there’s a personal motivation to come home sooner, rather than later. Reagan was president at that point; if he’d still been California governor it might have been different. But he had bigger fish to fry than me when he became U.S. president.

After your 1986 trial, what did you do with your personal, political and professional life?

I went to work in a pension law firm for a couple of years. Then I went back to my original work from 1970 right after law school, working for Berkeley Neighborhood Legal Services, part of the national legal aid program. I returned to that work at San Francisco Neighborhood Legal Assistance Foundation, which became Bay Area Legal Aid. I became a welfare law specialist, disability law, now called Temporary Assistance to Needy Families, food stamps, single adult welfare programs, unemployment insurance. Our role was representing individuals poor enough to qualify.

I always was champing at the bit, because I felt good about representing individuals, but the political part of me wanted to change the system that was making all of this happen. So, I did lots of advocacy work until 2013 when I retired. I joined the National Lawyers Guild in 1964 and became president of the local chapter in the ’90s.

And because I could use my real name again, I was able to legally marry Françoise.

You’re from a prominent New England family. Your grandfather was Connecticut’s U.S. senator and your father was a Connecticut state senator. How did a scion of the East Coast elite become part of the New Left?

My father, Alfred Bingham, was defeated around 1940 because he supported abortion or contraception. He co-founded the left-wing publication Common Sense, with writers like Upton Sinclair and Sinclair Lewis, before the New Deal. He visited Russia shortly after the revolution. I probably didn’t break the mold in the family as much as he did. My mother was perhaps more progressive, radical than he was. In Connecticut, we were a Democratic family in a sea of Republicans. My parents were an enormous influence on me.

What do you think movements fighting against white supremacy and capitalism can learn from studying George Jackson’s life and writings?

George’s book, Soledad Brother, was incredibly popular and brilliant. Although George’s death in 1971 temporarily set back the budding prisoners’ rights movement, the seed remained there. Angela Davis’s Critical Resistance is the logical outgrowth of the movement around George’s death [to dismantle the prison-industrial complex].

You’ll soon be 82. What would you say is the legacy of the movements you were a part of?

I was in the civil rights movement in Mississippi in 1963 and 1964, Freedom Summer, which shook me awake and resonates down to this day in an extraordinary way. One of my housemates in Mississippi was Mario Savio of the Berkeley Free Speech Movement. I was involved in the antiwar movement, which continues to reverberate.

My daughter Sylvia was killed in 2009 [while riding a bicycle]. I spend most of my time now doing road safety advocacy. Poor people are disproportionately killed, because the cars they drive are less safe, roads they walk on don’t have sidewalks or lighting, etc. I fully think of it is a continuation of my advocacy work, just in a different area.

Note: Screenings of A Double Life include: 6:30 pm on April 2 at the Roxie Theater in San Francisco; May 30 at United Theatre in Westerly, Rhode Island; and at the Visions du Réel Festival in Nyon, Switzerland, in April.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. We have hours left to raise the $12,0000 still needed to ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.