Truthout is an indispensable resource for activists, movement leaders and workers everywhere. Please make this work possible with a quick donation.

Between 1992 and 2013, the prison population in Brazil increased by more than 400 percent, compared with a 36 percent population growth over the same period, according to the country’s Ministry of Justice There are currently 711,463 prisoners incarcerated in the so-called penitentiary industry that prison rights groups argue is a commodification of human bodies.

“I was visiting a privatized female unit in the state of Espírito Santo, and entered the prison’s pharmacy, and the director proudly told me that all the inmates were 100 percent medicated with psychotropic drugs for three months,” said Jesus Filho, former member of the National Prison Clergy of Brazil. “That is population control. This was one of the most extreme cases of objectification of prisoners that I have thus far witnessed there.”

A majority of the convictions are related to economic and drug trafficking crimes. “The [prison] population is mostly black, poor people who had no chance in life; or education, health, and decent housing – people who end up in criminal activity as a last resort,” Fernanda Vieira, a lawyer from the Margarida Alves Collective, which offers accessible legal aid in the state of Minas Gerais, told Truthout.

The discourse of privatization in Brazil has gained credibility because state prisons are appalling, and health and education are catastrophic.

According to the 8th Annual Brazilian Public Security Report, of the 574,207 prisoners, 307,715 are black. “At least 40 percent of prisoners still do not have a conviction and are waiting for someone to tell them whether they are guilty or not. Most are young,” says Vieira. Likewise, data from the Brazil’s National Penitentiary Department (Depen) has documented that the number of female prisoners increased from 10,112 in the year 2000 to 35,039 in 2012. This represents an increase of 246 percent over the period. Most of the women are serving sentences for prostitution and drug trafficking.

Rights groups affirm that this trend in increasing arrests shows little sign of slowing down, pointing to growing social inequalities. In 2012, the UN warned that the gap between rich and poor was growing in many countries in Latin America. The region is considered to be one of most unequal and urbanized of the world, where 80 percent of the population lives in cities, and more than a quarter of the population lives in conditions of poverty. Twenty percent of the richest population has an average per capita income nearly 20 times the income of the poorest 20 percent. The most unequal countries based on income distribution are, in this order, Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, Colombia, Brazil, Dominican Republic and Bolivia.

Justified Privatization

The conditions of Brazil’s prisons system are often compared with the popularly conceived image of “Hell.” In 2012, in response to questions on his position on the adoption of the death penalty, former president of Brazil, Fernando Enrique Cardoso, said, “If I had to serve many years in one of our prisons, I’d rather die.”

From the time a person goes to a private prison, where your life is worth $940 per month, you cease being a human and you become a commodity.

Brazil currently ranks as the fourth-largest prison population in the world, coming after the United States (2.2 million), China (1.6 million) and Russia (740,000). Brazil has space for little more than half its prisoners. The National Penitentiary Information System (InfoPen) notes that there is a deficit in the prison system of 358,000 adequate spaces for prisoners, implying that each cell has more than double the occupation of its intended capacity. This is data that has been used as the main argument for the privatization of prisons. “The discourse of privatization in Brazil has gained credibility because state prisons are appalling, and health and education are catastrophic,” said professor Marta Machado of the São Paulo Law School and Getulio Vargas Foundation.

From Prisons to Profitable Companies

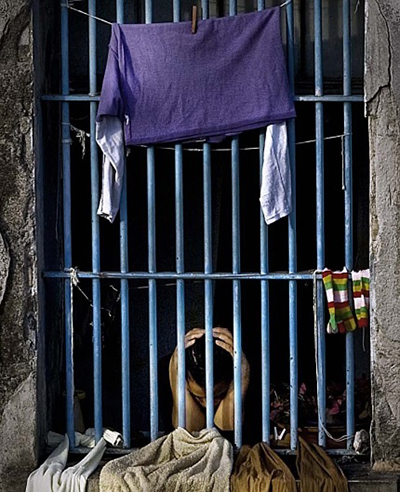

(Photo: Archive Pastoral carcerária Brasil)

(Photo: Archive Pastoral carcerária Brasil)

Masses of prisoners are an incentive that has aroused the interest of investors from the private security market. In 2009, the corporation Gestores Presiónales Asociados (GPA) won a concession through the public-private modality (PPP) to administer the first of these public-private penitentiary complexes, composed of five prison units, in Ribeirão das Neves, in the state of Minas Gerais. The company signed a 27-year contract, which may be renewed for another five years. GPA is a consortium made up of five companies, the majority being construction firms: CCI Construções S.A, Construtora Augusto Velloso S.A., Empresa Tejofran de Saneamento y Serviços, N.F. Motta Construções e Comércio y el Instituto Nacional de Administração Prisional – INAP.

In accordance with Article 1.134 of the Brazilian Civil Code, a foreign company needs authorization from the federal government to operate in Brazil through a branch. Therefore, it is difficult to identify transnational capital. “We are still not sure whether there is foreign capital in these complexes. But we can see that the individuals who formed the company in Minas Gerais are the same who were previously directors of public prisons; the corruption is very clear,” said Fernanda Vieira, who also provides legal support to several prisoners in the Ribeirão das Neves complex.

In 2013, the first prison complex was opened in Ribeirão das Neves, as well as the Integrated Resocialization Center of Itaquitinga, in the state of Pernambuco. According to a 2014 research report called “The First Public-Private Partnership Prison Complex in Brazil,” the PPP model represents an innovative form of cooperation between government and the private sector through concession contracts based on a determined period where construction, management and risk are shared. Therefore, the state pays the private consortium for the penitentiary service, while the operator has the opportunity to use the infrastructure and/or services in the pursuit of profitability.

US Influence

According to Professor Laurindo Dias Minhoto, of the Faculty of Arts and Humanities in the University of São Paulo, the privatization of prisons is a Brazilian model that shares certain elements of US private prisons, as well as the British model, which allows for private capital to finance public infrastructure. “The neoliberal project, especially the American style, seeks to turn all spheres of social life into a company, including the state itself, punctuated by an enterprising economic rationality,” affirmed Dias Minhoto in a March 2015 debate called “Public-Private Partnership in Brazil’s Prisons: Legal, Political and Ethical Implications.”

Luís Fernando Massonetto,professor of economic law at São Paulo University, shares with Truthout that the PPP model follows the logic of neoliberal policies in the sense of furthering the accumulation and expansion of the reproduction of capital. “The neoliberal logic in the world has been the multiplying of opportunities of capital accumulation alongside the increased repressive rationality of the state and social control. Financial deregulation on the one side, and ‘law and order’ on the other.”

In the document titled “Lessons Learned and Opportunities,” the Executive Manager of the PPP Central Unit in Minas Gerais, Marcos Siqueira Morães, alleges, among other things, that the complex aims to increase the efficiency of operations in infrastructure. This includes long-term contracts, risk sharing, managerial and financial, as well as ensuring profitability.

At the IV Congress of public management (CONSAD), held in 2011, with the participation of Siqueira Moraes, another document called “Sharing Profits of PPPs” was presented. It states that, for the private sector to participate in the construction of these projects, financial engineering is required that allows investors to raise funds more cheaply. Market risks and demands are totally or partially mediated by the state. This process resulted in what is now called “New Public Management,” which represents a scenario in which the state transfers the carrying out of certain policies to private capital, leaving in their hands the associated infrastructure.

Prisons in Company Mode

Jesus Filho does not doubt that the spaces in private prisons are cleaner and the food is much better than public units, but he expresses surprise with the flows of capital that this implies. “Privatization costs a lot. It costs 3,000 reales (US $940) per prisoner per month, and that is multiplied by 600,000 prisoners. How many millions is Brazil spending per month? It costs a lot,” said Filho in the March PPP debate.

Meanwhile, the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES), in a 2011 report called “Financing Infrastructure in Brazil: Prospects and Challenges,” frames PPPs as part of its long-term financing. “There is no loss because the PPP complex is being covered by BNDES and there has been no problem in meeting the demand of having more prisoners: in a weekend alone in Minas Gerais, hundreds were detained in a festival,” said Fernanda Vieira.

The main source of income for these prison complexes is from the state, with a higher cost than public prisons. However, the consortium GPA claims to have produced concrete results in the rehabilitation of the prisoners, with quality indicators that will be verified by the multinational firm Accenture. The firm has a presence in more than 56 countries, providing management consulting, technology services and outsourcing. According to “The First Public-Private Partnership Prison Complex in Brazil” research paper, the company’s commitment is to evaluate performance indicators, payments made by the state to the consortium and to assist in resolving potential conflicts.

“The big market of today is the creation of security technologies, logistics and infrastructure, the crime control industry,” says Dias Minhoto.

Sub-Minimum Wages

In the war of production costs, the main problem that rich countries and companies face are wages that cannot be reduced further, in contrast to labor struggles that seek to increase wages and better work conditions. One problem that is blurred with the privatization of prisons is that it may seem that the greater number of prisoners there are, the greater amount of cheap labor that is available. “It’s a process of commodification because prisoners do not have the ability to defend their labor rights,” said Fernanda Vieira.

Although this model of private prisons, called by US researcher and 1960s black liberation activist Angela Davis, the “Prison Industrial Complex,” has as one of its main objectives cheaper production costs of goods. In Brazil, it is a process that is under construction. “At the moment, the only cash flow is through the state and outsourced technology and service companies. We cannot help but notice that the business lobby is not limited with the expansion of prison policies. There is growing pressure from the business lobby for the use of new technologies of social control and surveillance,” says Fernando Massonetto.

Human Rights Violations

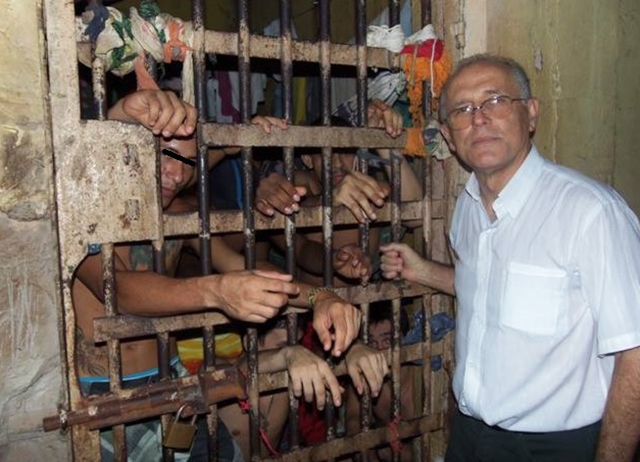

(Photo: Archive Pastoral carcerária Brasil)

(Photo: Archive Pastoral carcerária Brasil)

The new private prison complexes do not provide rehabilitation because they function under a logic of dehumanizing prisoners. “It’s all very cold and isolated. Visitations are just as degrading as in public prisons. From the time a person goes to a private prison, where your life is worth $940 per month, you cease being a human and you become a commodity. That is a violation of human rights. As of now, there is no access to education, health or work and the state supposedly covers this,” Fernanda Vieira told Truthout.

It is clear that this is “prison capital,” says professor Massonetto, quantified in managerial spreadsheets and guaranteed by the state to reduce business risks. “Control of the body was present in the production of social surplus during the old forms of slavery to the commercial exploitation of the workforce. Violence on the body was gradually modified, ranging from the decision of life or death of the slave to the most modern techniques of labor subordination to capital. What contemporary capitalism cynically exposes is the control of bodies is an essential input for the reproduction of prison capital,” said professor Massonetto.

A terrifying moment. We appeal for your support.

In the last weeks, we have witnessed an authoritarian assault on communities in Minnesota and across the nation.

The need for truthful, grassroots reporting is urgent at this cataclysmic historical moment. Yet, Trump-aligned billionaires and other allies have taken over many legacy media outlets — the culmination of a decades-long campaign to place control of the narrative into the hands of the political right.

We refuse to let Trump’s blatant propaganda machine go unchecked. Untethered to corporate ownership or advertisers, Truthout remains fearless in our reporting and our determination to use journalism as a tool for justice.

But we need your help just to fund our basic expenses. Over 80 percent of Truthout’s funding comes from small individual donations from our community of readers, and over a third of our total budget is supported by recurring monthly donors.

Truthout’s fundraiser ended last night, and we fell just short of our goal. But your support still matters immensely. Whether you can make a small monthly donation or a larger one-time gift, Truthout only works with your help.