Part of the Series

Voting Wrongs

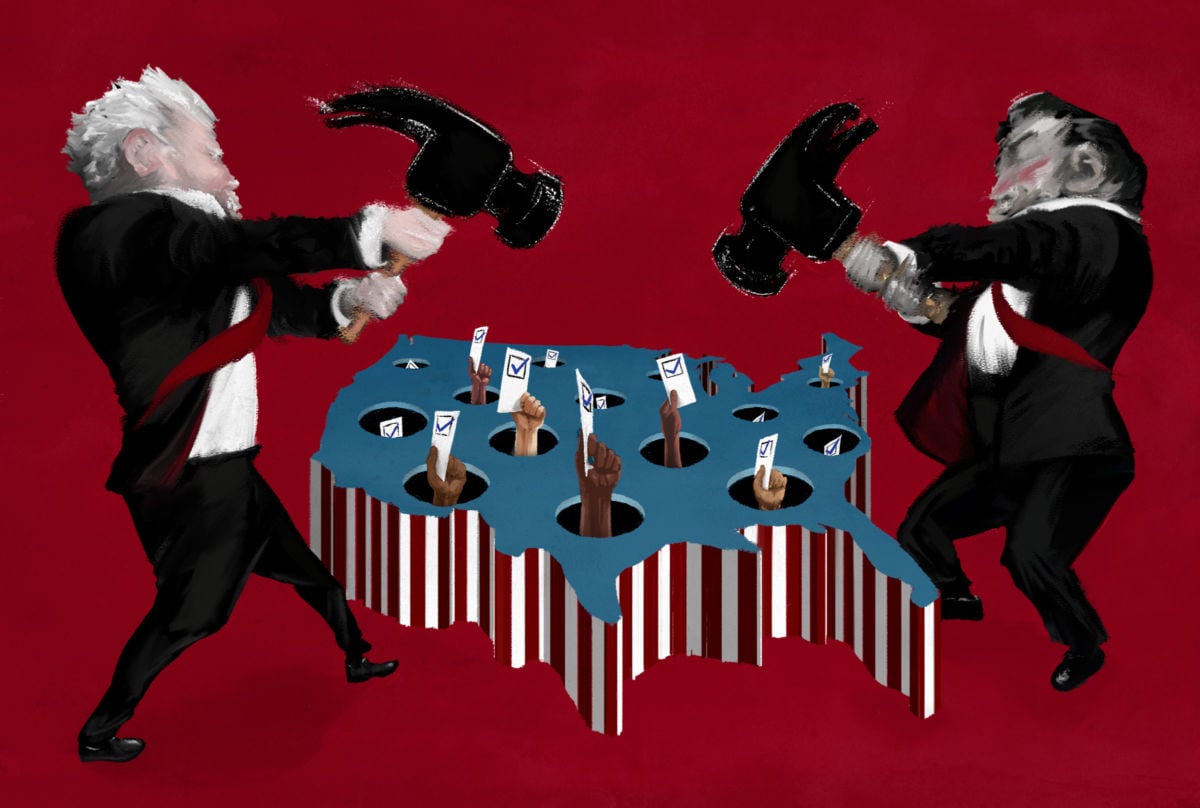

In the United States, children are taught that our country is synonymous with freedom and democracy. Our founding documents are treated with great reverence, despite the evils of chattel slavery and settler colonialism that are part of the legacy of many of its signatories. Beyond these textbook fantasies, however, the United States has a woeful history when it comes to a key aspect of democracy: voting. The Declaration of Independence said all men (and only men) are created equal. But the Constitution only gave a small fraction of the population — white male property owners — the power to vote (and no explicit right to vote provided for anyone).

Centuries later, the United States continues to deprive many people of this basic civic tool through sinister voter ID laws, disenfranchisement of millions of Americans with criminal records, and other remnants of Jim Crow that keep institutionalized racism alive in the U.S. According to the Sentencing Project, more than 6 million Americans remain unable to vote because of felony offenses.

It has been almost 20 years since the 2000 presidential race, in which the suppression of the vote (primarily in districts with nonwhite populations) was among the variables that led to the second Bush presidency and all of the war that came with it. Even among those who can vote, many find they are de facto disenfranchised due to the Electoral College/winner-take-all system, corporate money in politics and mass media consolidation. Gerrymandering, too, is problematic in the U.S. In June, the Supreme Court ruled that the federal government can’t challenge states on this issue.

These problems are apparent, advocates tell Truthout, when comparing the U.S. to other Western democracies, virtually all of which have a form of a national popular vote, proportional representation and a higher voter turnout than the U.S. For instance, the U.S. ranks 26 out of 32 countries in voter turnout, among members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), a coalition of wealthy nations.

“It is truly pitiful how the vote has been undermined in the United States. We are talking about a 56 percent voter turnout, which is embarrassingly low,” said Allegra Chapman, former director of voting rights and now a consultant for Common Cause, a government watchdog group, in an interview with Truthout. “I think there is a lot we can learn from other countries.”

Other Countries Allow Incarcerated People to Vote

“Without a vote, a voice, I am a ghost inhabiting a citizen’s space.” — Joe Loya, formerly incarcerated writer, on losing the right to vote after imprisonment.

When Sen. Bernie Sanders said at an April CNN town hall meeting that people in prison should be allowed to vote, it was widely portrayed as an extreme statement in dominant media outlets. Sanders’s opponents in the 2020 presidential primary distanced themselves from his stance. In a Truthout op-ed, Maya Schenwar said allowing people in prison to vote “should be wholly uncontroversial among all people who call themselves progressive.”

Indeed, this position is mainstream in many countries. One study covering 45 nations found 21 allowed all incarcerated people to vote, 18 allowed some to vote and 10 countries allow zero prisoners to vote. Only four countries had post-release restrictions: Armenia, Belgium, Chile and the United States, the report shows.

“In democracies the world over, being incarcerated does not strip someone of citizenship and the voting rights that come with it,” wrote Aubrey Menarndt, an international election monitor, in a New York Times op-ed, adding that incarcerated people “are encouraged to take their duties as citizens in a democracy seriously.”

It’s not surprising that the U.S. is in the minority on this issue, according to Seth Ferranti, who writes extensively on his years in prison. “Prisoners should retain all their rights despite being incarcerated. Incarceration is enough of a punishment,” Ferranti told Truthout.

Prisoners (whether they can vote or not) are often also unable to be civically engaged without consequences. In Massachusetts, for instance, then-Gov. Paul Celluci used executive action and made it illegal for prisoners to form a PAC in 2001, the year he took the right to vote away from prisoners.

“Authorities and prison officials are scared to death of prisoners organizing,” said Ferranti, who was a producer for the Starz documentary White Boy. “Anyone that shows any type of leadership in prison is thrown in the hole and put on diesel therapy* if not outright beat and even killed.”

Most Countries Don’t Have an Electoral College

Felony and prisoner disenfranchisement and the lack of a binding right to vote for Americans are just a few of the ways in which the country lacks the voting protections in line with the international community.

A 2016 study from Pew Research Center found that in 33 of 41 presidential democracies “the president is directly elected,” and 22 “require an absolute majority of the popular vote for election.” The U.S. is the only country where the popular vote loser can win the presidency.

“[It] might be telling that when we’ve advised a country on how to write a constitution, we have never told them to copy the Electoral College. Nor have we told them to let state legislators draw their own boundaries,” explains David Weigel in The Washington Post. “In 2012 our system elected a House of Representatives that lost the popular vote and in 2016 it elected a president that lost it, too. That has massive distorting effects on how our country works. For all our gifts, it’s something no other presidential democracy has to worry about.”

Oregon has recently passed a law that would guarantee its electors to the winner of the national popular vote. If enough states followed through with this — a power clearly granted to them in the Constitution — it could “have the effect of allowing those with the most votes to win,” Chapman said.

Colorado is also praised for its forward-thinking approach. The Voter Access and Modernized Elections Act of 2013, for instance, mandated that “mail ballots be sent to every registered voter for most elections … [and] shortened the state residency requirements for voter registration.” Pew Charitable Trusts says the new law yields “more efficiency,” and is “a better experience for citizens.”

FairVote, a national nonpartisan organization which fights for voting rights and reforms, advocates a method called ranked-choice voting (RCV), which allows voters to rank their favorite candidates to eliminate the “spoiler effect.” Under this system, if no one wins a majority on the first vote, they add second-place choices (and so on) until a winner is declared. For instance, in 2000, one could have voted for Ralph Nader first, with Al Gore as the second choice. The voter does not have to decide between their favored candidate and fear of the worst candidate. This could potentially widen our binary presidential system, which effectively enables two political parties to maintain power at any one time.

This method has been used in some local elections in the U.S. and was recently adopted by the state of Maine. Outside of the U.S., Australia, Fiji, Ireland and the U.K. (including Scotland and Northern Ireland at the local levels) have all used some form of ranked-choice voting.

Additionally, some countries with the highest turnout numbers have some form of compulsory voting. One advocate is Stanford Assistant Professor Emilee Booth Chapman (no relation to Allegra Chapman), who wrote an article in the American Journal of Political Science making this case.

“The case for compulsory voting rests on an implicit, but widely shared, understanding of elections as special moments of mass participation that manifest the equal political authority of all citizens. The most prominent objections to mandatory voting fail to appreciate this distinctive role for voting and the way it is embedded within a broader democratic framework,” the article states.

Toward a Future of Voting Equity

The U.S.’s systemic failures on voting obviously pre-date the presidency of Donald Trump. He has, however, added urgency to the debate, since many view Trump as a unique threat to democracy. His open bigotry and autocratic tendencies have put a scare into many who are starting to notice the fragility of democratic values.

The good news is this has put voting rights at the center of the national debate — although Ferranti notes, he had been waiting for people to notice how flawed the U.S. voting system can be.

“It seems like ever since Trump got elected, people and the media in this country are discovering things for the first time. I’ve been writing about this issue from inside since the late ‘90s,” Ferranti said.

The good news is, there’s no need to reinvent the wheel: The international community has already mapped a path to voting equity.

Outside of the United States, there are treaties and charters that are designed to protect the vote. The U.S. ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) in 1992 and is subject to periodic review, but has ratified fewer international voting treaties than most countries.

“Every citizen shall have the right and the opportunity … to vote,” says Article 25 of the ICCPR. This, according to Ali Rickart, in her comparative look at voting rights, is “considered customary international law.”

The U.N. Human Rights Committee further argues that if “conviction for an offence is a basis for suspending the right to vote” the suspension must be “proportionate to the offence and the sentence” and that those persons who may be “deprived of liberty but who have not been convicted should not be excluded from exercising the right to vote.”

FairVote has been pushing legislation calling for a constitutional amendment guaranteeing the right to vote for all Americans.

“While the U.S. Constitution bans the restriction of voting based on race, sex and age, it does not explicitly and affirmatively state that all U.S. citizens have a right to vote,” the group argues. “The Supreme Court ruled in Bush v. Gore in 2000 that citizens do not have the right to vote for electors for president.”

Another big fight is for universal registration, Allegra Chapman told Truthout. “People could be registered automatically. This would clear confusion over when registrations are due and who is eligible to register.”

As FairVote notes, “The government should not only facilitate registration; it should actively register adults who are eligible to vote as part of its responsibility to have accurate rolls. One hundred percent voter registration should be the goal.”

Meanwhile, Ferranti is encouraged that more Americans are at least talking about the fact that millions among us are denied the vote.

“When I was in prison, we were all just sitting there waiting for the rest of America to wake the fuck up,” he said. “We have woken up to an extent, but there is still a long way to go.”

* The phrase “diesel therapy” refers to a cruel means of punishment in which a prisoner is transferred from prison to prison, never staying in one location long enough to receive communication or visitation. They are subjected to especially restrictive restraints, among other indignities.