Last Sunday I worked in the Montefiore Medical Center Moses Division Emergency Department and I want to share with you the real-life story—and most certainly not the worst story.

To back up… I had some concerning symptoms that started the previous Sunday at about 10 a.m. but escalated severely by Tuesday night. I was “approved” for COVID testing only because I had these symptoms and, perhaps, due to my age.

I had the test on Thursday. I was told to call when I arrived, and then wait in my car for someone to call me in. The test was only supposed to take a few minutes. But when I arrived and called, I got a recording that said the office had moved. I made more calls, waited, called again. Almost two hours passed before someone finally tested me.

I was told my results would be ready within 24 hours. Friday came and went: no results. Not Saturday, not Sunday. On Monday I finally got the good news that I was negative.

However, due to the “new” protocols, I had been permitted to work the previous day—exactly seven days after my first symptoms, and 72 hours after I stopped running a fever.

I would have waited, but the Emergency Room sounded desperate, with many, many sick calls, so I agreed to go in at zero hour of my release from isolation: 10 a.m.

One Mask, One Gown

I floated around at first, but the newly designated COVID-Positive and Persons Under Investigation for COVID unit, awaiting their test results, was in dire need of a nurse; the three nurses there were holding over 30 patients. I took a few patients from these nurses (I took the Spanish-only speakers, as none of the other nurses spoke Spanish) and a few new patients, but I did not have the nine or 10 that they had.

There was only one tech (an advanced nursing assistant who can also perform electrocardiograms and urine tests and draw blood) for the entire unit.

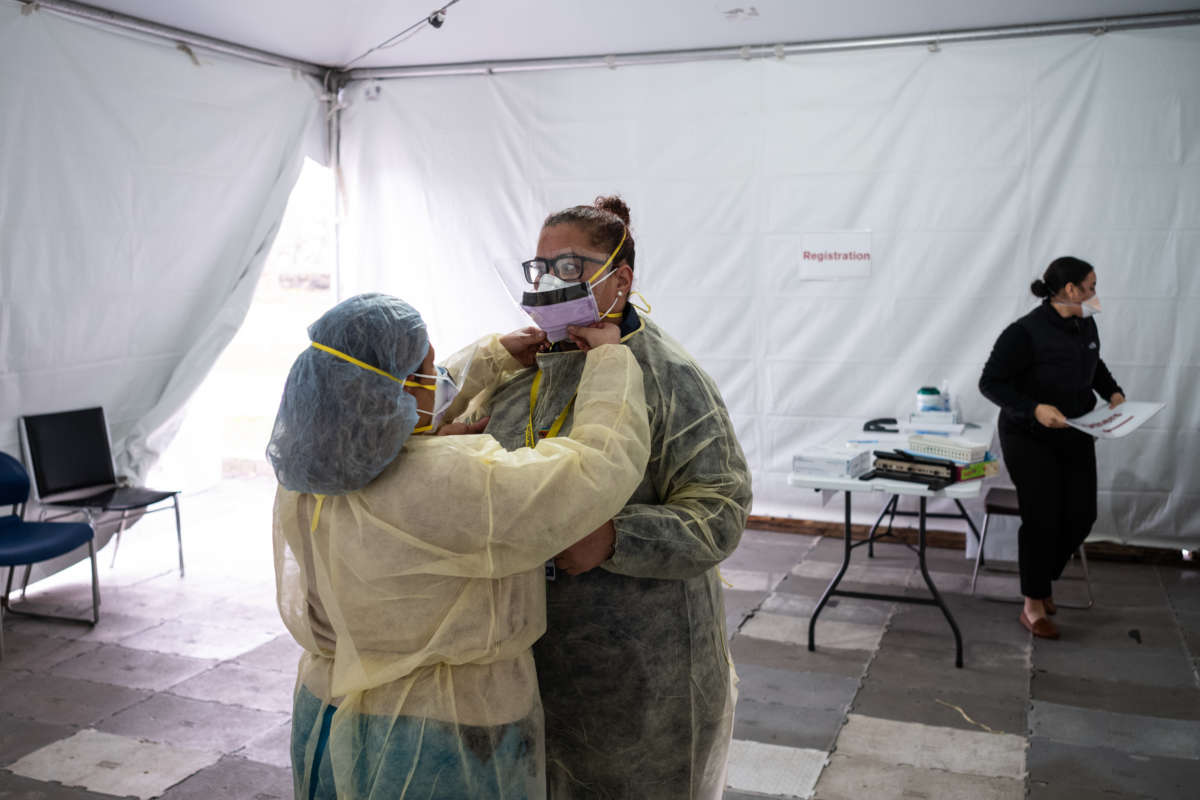

We had to beg for an N-95 mask. I received one N-95, and one yellow gown and a face shield. That was my “par,” my full complement of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), for the day. I was given a paper bag to store my N-95 and gown in when I went to break or was not using the N-95 (when charting or using the bathroom).

We all wore surgical masks when not wearing the N-95. I procured a head cover and booties.

Freezing Tents

The nurses in the triage tents were so cold that they were shivering, even in their coats. Many started having cold and cough symptoms.

They said that everyone from the nurse manager to top administration had known that it was too cold in the tents since they were first set up, but they couldn’t figure out how to help, apparently. With the freezing weather over the weekend, the situation had deteriorated. I was horrified—I found out that another nurse had been calling everyone over the week to no avail.

As of Monday morning, there was still no heat.

Short on Soap

I can’t even begin to describe the infection-control nightmare that exists in the Emergency Department. COVID-positive patients are side by side with people waiting for their test results (PUIs)—(as there are only two isolation rooms)—separated by curtains or nothing at all due to volume. Patients are waiting 24 or even 36 hours for beds.

Garbage was everywhere. I took the bins out of the one room that a COVID-positive patient was in and cleaned the room myself, removing trays, empty juice cups, trash, and stuff I couldn’t recognize. The housekeeping staff member—the only one—switched the bags for me and I returned the bins to the room.

In the West (Critical) Zone, there are COVID-positive, intubated, dying, and sick not intubated patients, mixed with who knows what. Nurses sometimes do and sometimes don’t wear gowns; docs the same. People of unknown status are being intubated at intervals next to patients who are also of unknown status, separated by curtains.

I swept the floor with my bootie-covered shoes and used my gloved hands to gather up the trash with that I found all around the patients. Many sinks had either no soap or no paper towels. Most sinks had only ice-cold water.

Begging for Juice

None of my patients had pillows; one 87-year-old man was lying in stale urine-stained bed, thankfully dried up and covered with a sheet.

My patients had not eaten except for turkey sandwiches, hardly any liquids, nor had they bathed. I gave them our heated warm wipes and bathed the older man myself (who had a low oxygen saturation, a preliminary danger sign, until I placed oxygen on him). I found his teeth in his jacket pocket and fed him from a warm tray.

I delivered trays to the hungry as much as I could and warm blankets to the shivering febrile patients in the same manner—but not to all, because I couldn’t, didn’t have the time. I ordered fruit and juice from the kitchen, as many patients were begging for these things—it seems to be helpful with this disease.

I translated a bit for the docs; phone use was a problem due to droplet/airborne/contact contamination. Many patients didn’t have armbands, also due to contact contamination concerns.

Sent Home Too Soon

We sent an older woman home who was PUI but no results because she looked and felt better.

I instructed her to engage in self-isolation at home and that we would call her when we got her results.

She said she lived with her daughter and six grandchildren in a one-bedroom apartment and her room was the living room. She couldn’t imagine how she could be isolated. She begged us to let her stay, to protect her family. Admission for social/borderline medical reasons is no longer permitted, due to the pending influx of deteriorating COVID patients. I told her at least not to cook until we knew her status.

I was so sad about this situation. But her story was not the only sad one.

I could do all of this because I only had about six or seven patients at a time, compared to the other nurses who had nine or 10 prior to my arrival. That number rose, of course, with the influx of new patients—no COVID beds available.

I was told this was “the best day yet.”

Grateful for Basics

Upon sign-out, we received a shipment of gowns and N-95s. The night shift, upon seeing the supplies acted as if Santa Claus arrived.

There were squeals of joy as nurses asked, “Can I have two gowns, really? Oh, how wonderful!”

It takes so little to make us happy.

We have no place to change our clothes and bag them, so I had to put my coat on over my uniform. Most staff who live in houses say they disrobe outside their homes and bag their clothes—then shower and change. They try to disinfect their cars. I live in an apartment so can’t do that.

I heard comments like: “Well, most of us are going to get it and some of us are going to die. That’s the way it is.”

These statements broke my heart. The way our patients are suffering broke my heart. There’s got to be a better way.

New York Nurses’ Demands

As frontline health care workers, we are concerned about the COVID-19 pandemic, and how we protect ourselves and our patients in the days and weeks ahead. We are calling on hospital administrators to implement the following:

1. Comprehensive Access to Personal Protective Equipment for Direct Patient Care: PPE is our first line of defense against COVID-19. All staff involved in direct patient care must have access to all necessary PPE.

2. PPE for All At-Risk Healthcare Workers: All staff who have other risk factors (e.g. pregnant, immunocompromised) should have access to PPE, regardless of their work area.

3. Hospitals Must Join Nurses’ Demand for Immediate PPE Supplies from Feds and NYS: Hospital execs must demand local, state, and federal officials take extraordinary efforts to secure the PPE supply chain including forcing manufacturers under the Defense Production Act.

4. Employee Access to COVID-19 Testing: Any health care worker involved in patient care should have guaranteed access to testing for the virus, regardless of symptoms.

5. Widespread Testing, No Rationing: Hospital execs must demand local, state, and federal officials make widespread testing available immediately, AND condemn any attempt to ration or policies that lead to disparities in access to testing, such as the NYC-DOH’s current guidelines.

6. Focus on More than PPE Conservation: The hospital must take immediate steps to implement administrative, engineering, and source controls and stop limiting PPE.

7. Give Frontline Caregivers a Voice in Decisions: The hospital must give frontline caregivers access to information and a voice in critical decisions, such as PPE protocols, reconfiguring space, modifications to practices that limit exposure, and staffing selection on COVID-19 units.

8. Develop Specialized Units, Expand Space for Patient Care, and Promote Cross-Training: We need to develop specialized areas to house COVID-19 patients and dedicated training on best practices for COVID care. We must utilize elective procedure areas or other spaces to eliminate overcrowding, and we need to provide full support for any staff assigned to unfamiliar areas.

9. Provide Childcare: The hospital should provide access to a pool of childcare providers, at least until city or county officials secure childcare for healthcare and other essential workers.

10. Provide Housing or Alternate Accommodations: Many health care providers have at-risk family members, so now is the time for the hospital to secure lodging arrangements at nearby hotels for staff who require them to keep working.

—New York State Nurses Association

Truthout Is Preparing to Meet Trump’s Agenda With Resistance at Every Turn

Dear Truthout Community,

If you feel rage, despondency, confusion and deep fear today, you are not alone. We’re feeling it too. We are heartsick. Facing down Trump’s fascist agenda, we are desperately worried about the most vulnerable people among us, including our loved ones and everyone in the Truthout community, and our minds are racing a million miles a minute to try to map out all that needs to be done.

We must give ourselves space to grieve and feel our fear, feel our rage, and keep in the forefront of our mind the stark truth that millions of real human lives are on the line. And simultaneously, we’ve got to get to work, take stock of our resources, and prepare to throw ourselves full force into the movement.

Journalism is a linchpin of that movement. Even as we are reeling, we’re summoning up all the energy we can to face down what’s coming, because we know that one of the sharpest weapons against fascism is publishing the truth.

There are many terrifying planks to the Trump agenda, and we plan to devote ourselves to reporting thoroughly on each one and, crucially, covering the movements resisting them. We also recognize that Trump is a dire threat to journalism itself, and that we must take this seriously from the outset.

Last week, the four of us sat down to have some hard but necessary conversations about Truthout under a Trump presidency. How would we defend our publication from an avalanche of far right lawsuits that seek to bankrupt us? How would we keep our reporters safe if they need to cover outbreaks of political violence, or if they are targeted by authorities? How will we urgently produce the practical analysis, tools and movement coverage that you need right now — breaking through our normal routines to meet a terrifying moment in ways that best serve you?

It will be a tough, scary four years to produce social justice-driven journalism. We need to deliver news, strategy, liberatory ideas, tools and movement-sparking solutions with a force that we never have had to before. And at the same time, we desperately need to protect our ability to do so.

We know this is such a painful moment and donations may understandably be the last thing on your mind. But we must ask for your support, which is needed in a new and urgent way.

We promise we will kick into an even higher gear to give you truthful news that cuts against the disinformation and vitriol and hate and violence. We promise to publish analyses that will serve the needs of the movements we all rely on to survive the next four years, and even build for the future. We promise to be responsive, to recognize you as members of our community with a vital stake and voice in this work.

Please dig deep if you can, but a donation of any amount will be a truly meaningful and tangible action in this cataclysmic historical moment.

We’re with you. Let’s do all we can to move forward together.

With love, rage, and solidarity,

Maya, Negin, Saima, and Ziggy