“Watchers have observed that there is a voting systems computer, in the central counting station … and it had wi-fi connectivity, and emails were being sent from that computer,” election security advocate Laura Pressley told Truthout in an exclusive phone interview, raising the alarm about vote-counting security in Dallas County, Texas.

Pressley worked for years as a device engineer and engineering manager in the semiconductor industry. She’s the founder of a non-partisan group called True Texas Elections that is monitoring elections all across the state – focusing especially on electronic voting machines and tabulators.

Pressley is not the only one concerned about wireless internet networks being anywhere near a voting machine or tabulator. Texas state law specifically prohibits it, mandating that “No voting system is ever connected to the internet at any point — either when votes are being cast or when they are being counted.”

That’s because wi-fi and internet connectivity are some of the easiest ways for malware to be introduced into a voting machine or tabulator. Once introduced, that malware could change election results on that voting machine, or on other voting machines infected via memory cards. The malware could then make its way into the vote tabulating system itself, potentially infecting the main election management system’s computers. If a wi-fi signal is in the tabulating room, the malware could get into the system that counts the votes quickly and easily, bypassing all of the other steps, and rapidly change the results of an entire county.

That’s why, Pressley says, “We are very concerned about that.”

She is concerned that the results in the contentious and high-profile contest between Republican incumbent Sen. Ted Cruz and his challenger, Democratic Congressman

Beto O’Rourke — or other races — could be impacted, or even changed.

Internet access is so interwoven into our daily lives, it’s hard for security experts to communicate just how dangerous this type of connectivity is to securing election results. But elections experts are trying desperately to get this message across, warning the public about wireless modems in voting machines in Wisconsin and Pennsylvania; and repeating over and over again that voting on the internet is not a good idea.

Dallas County Already Had Irregularities in Its Senate Primary

Pressley has had concerns about Dallas County’s security protocols for months. In March, when her team observed early voting tabulation there for the first time, they discovered the county’s computers spewing error messages and received an audit log with thousands of error messages, irregularities and results that did not add up.

What exactly was going on in the March 6, 2018, Dallas County primary? Incompetence, sloppiness, bad software design, fraud or just the standard fatigue of election officials under pressure? Elections and security experts say it is very difficult to know what happened.

In an October 31 press release, True Texas Elections announced that three affidavits are being filed with the Texas Attorney General. The affidavits claim there are multiple ballot counting discrepancies in the Democratic primary election results and ask for an in-depth look into Dallas County’s central counting station tabulation procedures.

O’Rourke won the primary by more than 40,000 votes, and election observers filing the affidavits are not claiming that the discrepancies were large enough to change the outcome of that race. However, they say races down the ballot may have been affected. They assert that the county’s own documents illustrate an elections’ office that is not counting the votes accurately and is not following correct security or election management protocols.

There are two data sets in question. One is a massive central tabulation systems audit log — close to 800 pages long — that presents a dense data challenge. It was obtained by election observers who then passed it on to True Texas Elections. The other records in question are the election results themselves that were released by the county following the primary. The county website says that the results are “Unofficial,” which would seem odd for a primary held on March 6. But an assistant administrator at the Dallas County elections office said that they were having trouble with their Clarity Software Suite vendor, and that the results were actually final.

That online software, responsible for displaying the results, is not the only technical issue the county is having. When those election results are compared with the Official Voter Democratic Party Rolls, obtained via open records requests, there are more votes than voters; something that is never supposed to happen, but which experts we spoke to claim is surprisingly common.

Joe Kiniry, the CEO and chief scientist of Free and Fair, a company that develops and implements software for election audits, said in an email: “Witnessing more votes than voters is very usual and usually triggers a process and data audit by the County Clerk (usually before certification).” Since this is well after certification, it would appear that no such audit took place and it is unclear if the county was aware of the discrepancies. The county elections administrator, Toni Pippins-Poole, declined multiple requests for comment.

A preliminary pass with the data revealed that differences between voters and votes occurs with troubling frequency. Because of the urgency of getting this information to the public we are releasing the data earlier than we normally would, but we have had four separate computer, analytics and elections security specialists examine various aspects of the data.

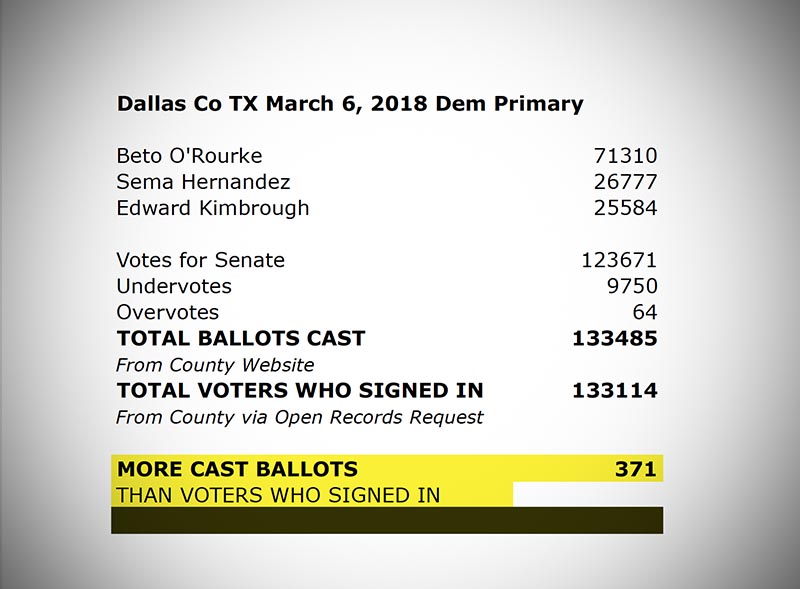

Records downloaded off the county website show that 133,485 total ballots were cast in the Democratic race for Senate. But the list of voters who voted shows that only 133,114 Democratic voters voted in that primary. That creates a difference of 371 more ballots cast than voters who voted. It is unclear how the county works their provisional ballots into their total numbers, but there were only 35 provisional ballots in that race, not enough to account for such a large difference.

Duncan Buell, a professor of computer science at the University of South Carolina and an election technology adviser to that state’s League of Women Voters, says he has seen it all. “In my own county in 2010 they managed to get all the vote counts wrong for one school board election, so none of the seven candidates actually got the right total.”

He acknowledges the tabulation errors in Dallas County could be fraud, “It certainly is possible that this indicates that they’re stuffing the ballot box.” But he says he is more concerned about election night fatigue and overload. “What I am suspicious of is that overworked, tired, people on election night, with hundreds of these things to upload, won’t get it right.”

Digging further through the Dallas data reveals some seemingly implausible results. In precinct number 3807, more than half of 393 voters did not cast a vote in the Senate race. In precinct number 3806 there were 163 voters, but 302 votes. In precinct 3311 there were 112 voters who managed to cast 186 votes and in precinct 1713, there were 55 voters who were so enthusiastic that they cast 119 votes.

Kiniry from Free and Fair suggests that the best place to look for answers would be the under and over vote totals – the terms used when voters don’t vote on a ballot, or vote more than once when not permitted. The data to make that assessment – a breakdown of those types of votes by precinct – is not currently available, but there were only 64 over-votes reported in the entire race. Professor Buell suggests that the best place to look for answers are on other logs that the voting systems create, but Pressley says the county refused to give her those logs.

Buell indicated that although he sees an almost constant flow of small and sometimes larger errors in election results, “Three hundred and fifty is big enough that it should be flagged.”

Kiniry agreed, saying, “These kinds of things are indicative of either serious data handling, process, technology, or procedural problems or malfeasance,” (a fancy word for fraud) and that it “should have been examined closely during canvassing and post-election audit.”

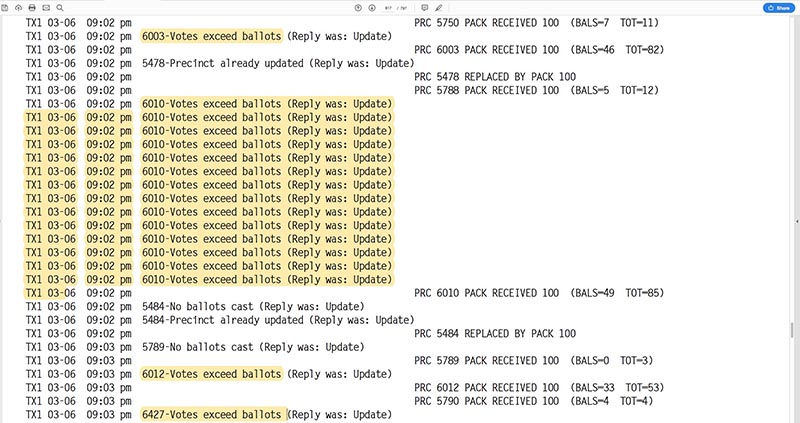

Pressley expressed her concern that if foul play was involved, it could be some kind of test run for the current election. Her team found page after page of error messages in the systems audit log they examined. In particular, they found an error message that corresponded to the problematic results: “Votes exceed ballots” is repeated over and over again throughout the log.

Kiniry counted it more than 3,000 times, saying, “These logs, if they are untampered with, certainly indicate a system test or use that was full of erroneous and problematic attempts at using the EMS [Election Management System].” He also was highly critical of the apparent lack of encryption on the log.

ES&S, the voting equipment vendor for the county, said in an email that the “Votes exceed ballots” error message “isn’t always indicative of an issue or error.”

But the ES&S manual lists that error message specifically as a reason to suspend the precinct, saying on page 347, “suspend a precinct if the number of votes in any contest exceeds the number of ballots cast.”

“The computer’s job is to count, so I would most certainly be concerned if something is wrong with how the computer is counting,” says Bennie Smith, a computer programmer we turned to in an effort to put the incident in context. “I would be trying to halt whatever the counting method is.”

Smith experienced a problematic election tabulator in Memphis, Tennessee. He was featured in a Bloomberg Businessweek investigation after he photographed poll tapes showing that 546 people had cast ballots in a Memphis precinct. But the county tabulator showed only 330 votes. According to Bloomberg, “Forty percent of the votes had disappeared.”

“I was the person that identified the problems here in Shelby County,” he said. “I was doing a study of how votes could originate in one place and then change when they got to the central tabulator.”

After the Bloomberg investigation, the election administration in Memphis changed and in the following major local election, a wave of women and people of color suddenly won their elections, including eight Black women who were featured in an MSNBC piece exploring the transformation of the Memphis electoral process.

Smith says that the issue of the central tabulator they experienced in Memphis is similar to the issue Pressley claims is occurring in Dallas – that there is some kind of problem with the central tabulator count. Smith, who experienced highly suspect behavior in his county personally, believes that these types of errors could be a sign of tabulation problems and need to be investigated. “I would want to look at those ballots … to rule out that nothing improper or inappropriate … happened.”

According to Verified Voting — a nonprofit that advocates for transparency in elections — Dallas County has 797 precincts that have been using touch-screen voting machines with no paper trail, throughout early voting. It will be difficult, if not impossible to determine the correct vote total on those machines, if there has been a tabulation error.

Some of the voting machines where the errors seem to have occurred were from hand-marked paper ballots that can be examined and compared to the computer’s totals. The ballots are not open to the public to examine, but Pressley says that the Texas Attorney General’s office is looking into the matter. In response to an inquiry, the Attorney General’s office said, it “does not confirm or deny the existence of investigations.”

Pressley says that Dallas County Democratic and Republican Party officials have now committed to providing observers at the tabulation of the votes on Election Day, but that as far as she can tell, those commitments are not being met, and the tabulation of early voting is proceeding without supervision.

Across Texas and other states like Georgia reports of voting machines flipping votes have put voters and candidates on edge. Elections experts across the country have called on congress to mandate hand-marked paper ballots for all elections and implement robust and meaningful audits to increase public confidence in the elections process. Meanwhile election officials are beginning to vocalize their concern that not enough resources are available to them to meet the mounting security challenges of a modern election. At a recent hackers’ conference, Alex Padilla, California’s secretary of state and chief elections officer, asserted fiercely that states need more assistance from the federal government in order to fully protect the vote, saying, “Let me be abundantly clear. We need more resources.”

Trump is silencing political dissent. We appeal for your support.

Progressive nonprofits are the latest target caught in Trump’s crosshairs. With the aim of eliminating political opposition, Trump and his sycophants are working to curb government funding, constrain private foundations, and even cut tax-exempt status from organizations he dislikes.

We’re concerned, because Truthout is not immune to such bad-faith attacks.

We can only resist Trump’s attacks by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser, and we have only 48 hours left to raise $22,000. Please take a meaningful action in the fight against authoritarianism: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout. If you have the means, please dig deep.