Part of the Series

Planet or Profit

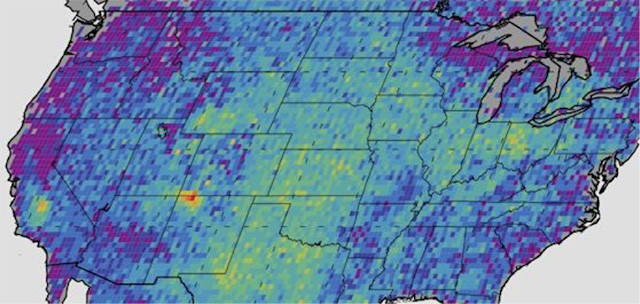

While some connected to the oil and gas industry have tried to argue that the Four Corners methane hot spot — the largest concentration of methane emissions in the nation — is naturally occurring due to underground coal formations, a new study definitively links the hot spot to fugitive methane leaks from oil and gas processing sites in New Mexico.

Researchers with National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the California Institute of Technology conducted research by flying over a 1,200-mile portion of the state’s San Juan Basin using specialized cameras, and found more than 250 high-emitting sites, including gas wells, processing plants and storage tanks that have helped fuel more than 50 percent of the methane hot spot.

According to the study, published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, more than two-thirds of the massive plume — which accounts for nearly a tenth of the oil and gas industry’s annual emissions — is coming from only 25 mostly oil and gas processing facilities. Only a few methane sources surveyed by researchers came from natural seeps from underground formations, and one included a vent from a coal mine.

In 2014, San Juan county oil and gas producers reported nearly 1,038,103 metric tons of methane emissions. During the past year, the Bureau of Land Management has taken action to limit methane emissions in the federal and tribal lands in the San Juan Basin.

After a satellite-based study released the first image of the hot spot in 2014, researchers and scientists have sought to identify its causes. This week’s study puts to rest arguments that minimize the oil and gas industry’s role in causing the plume.

“This is low-hanging fruit,” said Thomas Singer, who is senior policy advisor at Western Environmental Law Center, referring to the need for the industry to control and capture its methane emissions. “All of the oil and gas emissions have known solutions. Many of them are not costly…. This is eminently doable.”

Because only a fraction of the super-emitting sites are disproportionately contributing to the plume, the study concludes that reduction of these emissions can be easily achieved through better monitoring and detection practices. Likewise, Singer points to a report by ICF International which found that collectively, leaks, flaring, and venting from oil and gas sites on tribal and federal land in New Mexico set the national record for waste — squandering nearly $100 million worth of gas in 2013.

Such fugitive methane leaks from oil and gas infrastructure are not limited to sites in the San Juan Basin but are pervasive at production sites on shale formations nationally. Oil and gas production and processing sites in North Texas’s Barnett Shale region, for instance, emit thousands of tons of methane into the air every hour. Combined, the emissions are even larger than California’s Aliso Canyon leak that vented an estimated 96,000 metric tons of methane into the atmosphere during a period of four months.

But Singer takes issue with some of the researchers’ conclusions, arguing that the scale of their recommendations is not significant enough. The researchers state that the disproportionate number of large methane sources suggests that mitigation of the area’s total emissions requires “identifying and fixing a few emitters.” Rather, Singer and other environmental advocates want to see all of the emission point sources properly regulated.

“What we’re saying is, just controlling those 250 [high-emitting sources], isn’t enough; you might get at half the emissions, but you still haven’t gotten at [the other] half,” Singer told Truthout.

The study comes as the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Bureau of Land Management are finalizing new comprehensive oil and gas methane emission standards for already-existing sources. The EPA has begun a formal process requiring companies to provide information to help regulators develop the new rules, and anticipates concluding the process in the first part of 2017. In May of this year, the EPA issued new rules to cut methane emissions from all new oil and gas emission sources by nearly half over the next decade, under President Obama’s Climate Action Plan and the Clean Air Act.

Methane is the strongest of the natural greenhouse gases and is 86 times more potent than carbon dioxide in terms of trapping heat in the atmosphere in its first 20 years. As more and more methane is released into the atmosphere, positive feedback loops created by methane emissions are speeding up global temperature rise and climate disruption. “The more [of] that methane that you get out of the atmosphere now, the more you are reducing near-term climate [disruption],” Singer told Truthout.

But 13 states are now suing the Obama administration over new EPA rules curtailing methane emissions at oil and gas production and processing sites. West Virginia, which filed the suit, and 12 other states are arguing that the rules are “unnecessary” and would add “burdensome” costs.

“I think it’s just a knee-jerk reaction to fight all oil and gas rules,” Singer said. “It’s just a move in the chess game.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $50,000 in the next 9 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.