Part of the Series

Gas Rush: Fracking in Depth

Planet or Profit

Honest, paywall-free news is rare. Please support our boldly independent journalism with a donation of any size.

Federal regulators approved at least four hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,” operations in the Santa Barbara Channel off the California coast this year by signing off on minor revisions to permits that regulators “categorically excluded” from environmental impact reviews. Now, an environmental group plans to take legal action if two federal agencies fail to halt offshore fracking and conduct the reviews that activists say are required under federal law.

Federal regulators, environmentalists argue, do not know enough about the risks posed by offshore fracking to assure the public that the technology is safe, and few regulators understood that fracking technology had been deployed in the Pacific Ocean before journalists and watchdogs started asking questions and filing information requests.

In July, a Truthout investigation confirmed that the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE), the federal agency that issues offshore oil and gas permits, gave the oil firm DCOR a green light to use fracking technology to stimulate oil production from a well 1,500 feet from a seismic fault under the Santa Barbara Channel. Since then, new documents released to Truthout under the Freedom of Information Act show that, earlier in 2013, BSEE also gave DCOR permission to frack three other wells in the area. The fracking operations are scheduled to take place in early 2014.

Unconventional fracking operations on land, which are typically much larger than offshore fracks, have ignited a nationwide controversy, and Californians were alarmed to learn that similar technology is being used in sensitive marine areas without reviews that critics say are required under the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA).

On October 3, the Center for Biological Diversity notified BSEE and its sister agency, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), that the group would take legal action if the agencies fail to suspend fracking operations in the Pacific Ocean and review fracking’s potential impacts on marine environments.

“Oil companies are fracking California’s beautiful coastal waters with dangerous chemicals, and federal officials seem barely aware of the dangers,” said Miyoko Sakashita, an attorney and ocean program director at the Center For Biological Diversity. “We need an immediate halt to offshore fracking before chemical pollution or an oil spill poisons the whales and other wildlife that depend on California’s rich coastal waters.”

The group recently won a landmark lawsuit on similar grounds in California that halted fracking on thousands of acres of federal lands. A federal court ruled that the government violated NEPA when it leased public lands for fracking without preparing an environmental review.

Offshore drilling remains controversial in the Santa Barbara Channel because of the catastrophic 1969 oil spill that helped spark the modern environmental movement, which worked with government to establish laws such as NEPA.

A BSEE spokesman was not available for comment because of the federal government shutdown.

Categorical Exclusions and Fracking Wastewater

According to internal BSEE documents, the four DCOR frack jobs, known as “frac-packs” or “mini-fracks,” were approved under minor modifications to existing drilling permits that already were “categorically excluded” from the kind of NEPA reviews that environmentalists are now demanding. BSEE issues these exclusions when reviews indicate that a proposed activity is not expected to have significant impacts on the environment.

In the wake of the massive Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, the Interior Department reorganized its offshore drilling regulatory agencies and created BSEE and BOEM. Since the 2010 spill, the use of categorical exclusions to exempt drilling projects from NEPA reviews has been under public review at both agencies.

Before the oil spill in the Gulf, federal regulators were approving new and risky technologies for use in deepwater drilling projects under categorical exclusions and other NEPA exemptions, according to Brian Segee, an attorney for Environmental Defense Center (EDC) in Santa Barbara.

“This is history repeating itself in a very troubling way,” Segee said of the fracking operations in the Santa Barbara Channel.

BSEE officials say that offshore fracking operations are rare, much smaller than unconventional onshore operations, and regulators carefully review the permit modifications for offshore fracking.

Environmentalists, however, say that regulators and the public do not know enough about the safety of new offshore fracking technology, which uses a highly pressurized cocktail of salty water, sand and chemicals to break up undersea rock formations and harvest hard-to-reach oil reserves.

“This is a modification of existing technology that poses a lot of risks that [BSEE regulators] never studied and were apparently not aware of, and now they turn around and are rubber-stamping approvals,” Segee said.

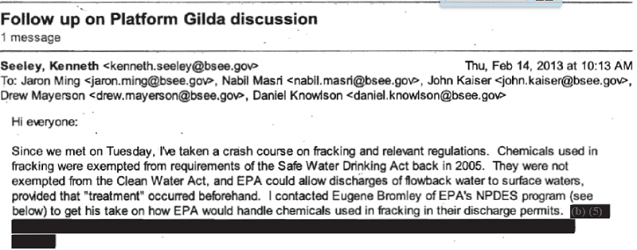

Internal emails released to the EDC and Truthout show that Kenneth Seeley, the BSEE official who would later perform Categorical Exclusion Reviews for DCOR’s drilling permits and fracking modifications, said in February that he took a “crash course” in fracking and disposal of fracking wastewater, which ranks high among the concerns of environmentalists:

At the time, inquiries from activists and news outlets such as Truthout had sent regulators scrambling to understand offshore fracking technology and the scope of fracking in the Pacific region, according to reviews of internal emails. In earlier communications, officials claimed that offshore fracking had occurred only twice in federal waters of the Pacific since the 1990s, but a “fact sheet” later released to Truthout claimed that fracking had occurred 11 times in Pacific federal waters. That number was later revised to 12 in media reports.

Seeley had a reason to be concerned. Fracking wastewater can contain dangerous chemicals that are added to fracking fluids and other pollutants, but fracking fluids and wastewater are exempt from federal hazardous-waste requirements and some clean water laws. Environmentalists worry that the wastewater could harm marine environments.

DCOR plans to pump wastewater from its fracking operations to an onshore treatment facility then send the fluids back to the drilling platform to be reinjected into underground formations or dumped overboard, according to BSEE documents. Seeley confirmed with Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) officials that this plan was consistent with a general discharge permit issued by the EPA for operators in the region.

In his correspondence with Seeley, EPA permit official Eugene Bromley said the language in the general wastewater discharge permit “would seem broad enough to include fracking fluids.” He also said, however, that the regulations of discharged chemicals pertaining to that the permit were written up in 1993, before fracking technology was introduced.

The chemical contents of fracking fluids often are kept secret by the industry, which considers the formulas to be proprietary information.

Seeley later asked Bromley if drilling firms would need special permission from the EPA to discharge fracking chemicals or if special permission would be needed only if the fracking chemicals were not commonly used before 1993. In his response, Bromley said pollutants that “may be present” in offshore fracking waste were considered in EPA guidelines, so “no special requirements” beyond those in the existing permit were needed to discharge the waste into the ocean.

The emails raised some red flags for Segee, who reviewed them as part of a Freedom of Information Act request by the EDC.

“It’s a pretty suspect conclusion, given the age of the language [Bromley] is relying on and given the fact that we don’t know what’s in the fracking fluids,” Segee said. “The fact is that the chemicals and the well stimulation that’s used today is pretty different in character than what was being done 20 years ago.”

Geohazard Reviews and Seismic Faults

Environmentalists are demanding further reviews of offshore fracking, but there is one type of review the BSEE officials completed before approving the DCOR projects – a “geohazard review.”

There are several active seismic faults under the Santa Barbara Channel, and BSEE officials reviewed DCOR’s fracking plans for potential geologic hazards.

Truthout obtained copies of the four reviews and confirmed that the fracking operations would not intersect any “interpreted fault splays.” One well, however, is 1,500 feet away from the World’s End Fault. In their review, which was partially redacted, the regulators determined that there was no pathway for drilling fluids or oil to reach the fault, which appears to be at a safe distance.

Truthout gave US Geological Survey officials in California a copy of the geohazard review and asked for a second opinion, but the government geologists said that they were unable to arrive at a conclusion. The main problem, they said, was that the reviews provided too little geological information, especially because key segments were heavily redacted.

Holding Trump accountable for his illegal war on Iran

The devastating American and Israeli attacks have killed hundreds of Iranians, and the death toll continues to rise.

As independent media, what we do next matters a lot. It’s up to us to report the truth, demand accountability, and reckon with the consequences of U.S. militarism at this cataclysmic historical moment.

Trump may be an authoritarian, but he is not entirely invulnerable, nor are the elected officials who have given him pass after pass. We cannot let him believe for a second longer that he can get away with something this wildly illegal or recklessly dangerous without accountability.

We ask for your support as we carry out our media resistance to unchecked militarism. Please make a tax-deductible one-time or monthly donation to Truthout.