Did you know that Truthout is a nonprofit and independently funded by readers like you? If you value what we do, please support our work with a donation.

Natural hair braider Ashley N’Dakpri knows her knots. She practiced as a child on friends and family, attended beauty school in the Ivory Coast, and has 20 years of professional experience in the United States. Yet that’s not enough in Louisiana.

The Louisiana Board of Cosmetology requires braiders to spend a year or more in a state-licensed school, whether they need the training or not. This works well for industry insiders on the board, composed of beauty school owners and licensed cosmetologists. They have financial interests in forced schooling and high barriers to market entry.

Meanwhile, people like N’Dakpri are stuck on the outside looking in. She has received multiple citations for operating Afro Touch Hair Braiding, a state-licensed salon in Gretna, Louisiana, without also having state-issued credentials for herself and her employees. Braiders who want to avoid fines must either earn a cosmetology license or an alternative hair design permit, which requires at least 500 hours of formal training, mostly covering conventional cosmetology techniques that braiders do not use.

Besides being largely irrelevant, alternative hair design programs are expensive and hard to find. They are also remedial for experts like N’Dakpri. If anything, she should be teaching classes, not paying to sit behind a desk or work for free in a student salon, owned by the very people who want to put her there.

Louisiana braiders can get around the requirement by moving to any bordering state. Arkansas, Mississippi and Texas allow braiders to work without government permission, which makes sense considering the occupation involves no cutting, dyeing or heat — or anything realistically dangerous.

N’Dakpri could also switch careers, sacrificing an essential part of her cultural identity.

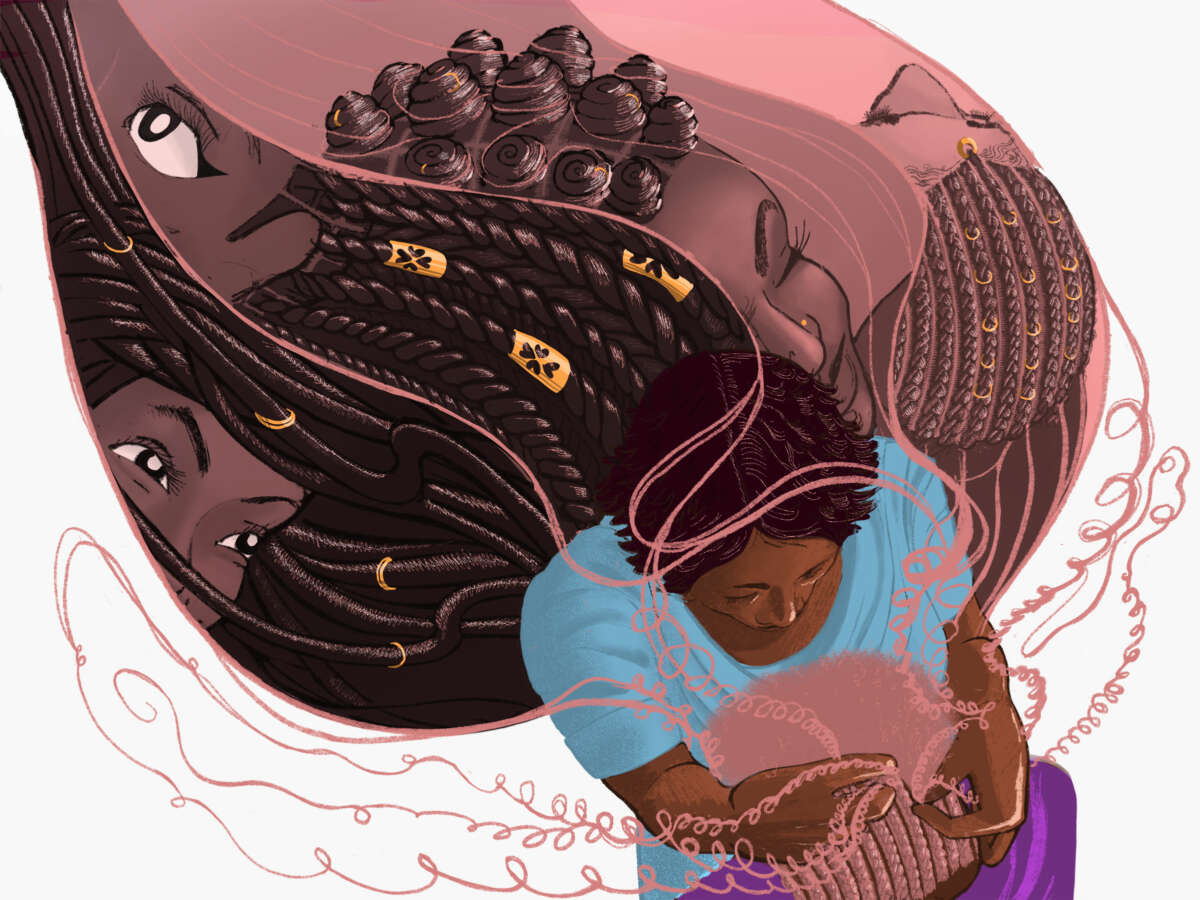

Natural hair braiding has distinct historical and racial roots, originating centuries ago in West Africa. People from the region, especially women, regularly learn the craft as children or teens. “I don’t understand why I need to get a license to braid hair, when I’ve been doing so for happy customers for years,” N’Dakpri says.

Policing Black hair is nothing new. As far back as 1786, Louisiana passed the Tignon Laws, which forced Black and biracial women to cover their hair in public. Other states adopted their own forms of hair discrimination. California and New York responded in 2019 with reforms that allow people to wear or treat their hair however they desire without reprisal. Yet people cannot hire whoever they want to braid hair in many places. Natural hair braiders still face regulatory hurdles in 17 states and Washington, D.C.

N’Dakpri decided to fight back. So in 2019, she filed a lawsuit in state court to invalidate Louisiana’s regulatory scheme. Our public interest law firm, the Institute for Justice, represents her and her aunt, Afro Touch founder Lynn Schofield.

The women make a simple argument: People have a right to earn an honest living in their chosen occupation without moving far away or paying thousands of dollars for skills they already possess. Most people would agree, but not the judge. On July 12, 2023, he dismissed their case, deferring to the board’s rulemaking authority.

The decision hinges on a judge-made doctrine called “rational basis review,” which courts have been using to excuse regulatory overreach since 1938. All the government has to do to survive rational basis review is articulate a legitimate state interest for meddling. No evidence is necessary that regulations achieve their intended purpose. Judges accept speculation, good intentions and after-the-fact rationalizations.

The idea is to protect separation of powers. Courts want to give the legislative and executive branches latitude, so judges become extremely deferential. Soon nobody in government is accountable to the constitution. Judges have used rational basis review to affirm “unjust,” “unfair,” “unwise” and “foolish” laws. The U.S. Supreme Court even allows “stupid laws.” This is a problem.

Almost anything goes as long as laws do not infringe on rights courts deem “fundamental.” These include things like free speech, voting and marriage, which get a higher degree of scrutiny. Providing for your family does not make the cut. Louisiana and other states acknowledge this right exists but put it in a lower tier and refuse to protect it with rigor.

Rather than give up, N’Dakpri and her aunt will appeal in the coming months and push forward to the Louisiana Supreme Court, if necessary. They can look to the brothers of Saint Joseph Abbey for inspiration. These monks, based at a monastery in Covington, Louisiana, took on rational basis review and won in 2013.

Their case started when they announced plans to sell handcrafted caskets without state permission. The Louisiana State Board of Embalmers and Funeral Directors threatened them with criminal fines if they did not first obtain a funeral director license. This made little sense, considering the monks had no interest in being funeral directors.

They sued in federal court to overturn the licensing requirement and prevailed at the Fifth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. “The great deference due state economic regulation does not demand judicial blindness,” a unanimous panel of judges held. Although rare, other victories have followed. Texas eyebrow threaders, Pennsylvania property managers and Georgia lactation consultants have all overcome rational basis reviews.

Louisiana braiders hope to be next. Their case matters, and not just for employees and customers. Anyone who works to pay rent or buy groceries should be concerned. If regulators can come after lower-income professionals at safe, responsible businesses like Afro Touch, they can turn anyone into a criminal.

A terrifying moment. We appeal for your support.

In the last weeks, we have witnessed an authoritarian assault on communities in Minnesota and across the nation.

The need for truthful, grassroots reporting is urgent at this cataclysmic historical moment. Yet, Trump-aligned billionaires and other allies have taken over many legacy media outlets — the culmination of a decades-long campaign to place control of the narrative into the hands of the political right.

We refuse to let Trump’s blatant propaganda machine go unchecked. Untethered to corporate ownership or advertisers, Truthout remains fearless in our reporting and our determination to use journalism as a tool for justice.

But we need your help just to fund our basic expenses. Over 80 percent of Truthout’s funding comes from small individual donations from our community of readers, and over a third of our total budget is supported by recurring monthly donors.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser to add 432 new monthly donors in the next 7 days. Whether you can make a small monthly donation or a larger one-time gift, Truthout only works with your support.