Part of the Series

The Road to Abolition

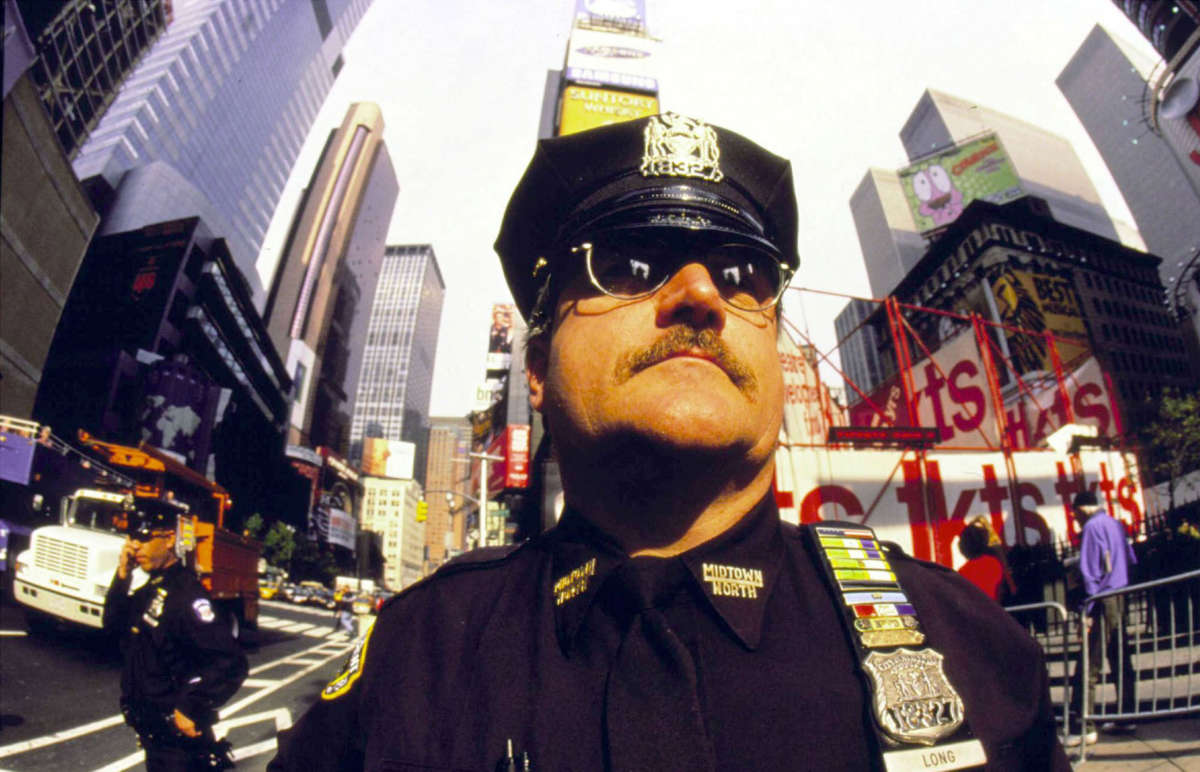

Across the United States, Democratic politicians are renewing their commitments to 1990s-era crime policies. From New York City Mayor Eric Adams instructing the NYPD to increase misdemeanor arrests, to the Detroit police cracking down on noise and “urban blight,” to Los Angeles’s City Council intensifying the criminalization of homeless people, the hallmarks of broken windows policing are heralded as solutions to the supposedly unprecedented national crime surge. At the national level, President Biden’s “Safer America Plan” promises to increase federal funding for local law enforcement and put 100,000 more cops on the streets in community policing programs — a direct repeat of President Bill Clinton’s notorious C.O.P.S program, which distributed millions of federal funds to law enforcement, escalating policing and arrests nationwide.

While proponents pretend that such practices do not constitute broken windows policing tactics but “quality of life” or “community policing,” in fact, there has never been a division between these policing practices, logics or outcomes. While technocratic criminal justice practitioners advocate for these policies as simply following “evidence-based practices,” this is simply not the case. We are witnessing a liberal law-and-order backlash to anti-racist activism against policing. Through scapegoating abolitionist movements to defund the police and more moderate criminal justice reforms as the source of violent crime, Democrats are returning to the very playbooks that propelled mass incarceration.

One place we can clearly see this dynamic occurring is in New Orleans. After years of grassroots success in pushing city leaders to enact criminal justice reforms, the mayor and city council of New Orleans have implemented a series of tough-on-crime policies throughout 2022. Predicated on the false assertion that the current murder rate in New Orleans has reached heights not witnessed since the 1990s, Mayor LaToya Cantrell has championed the relaunch of a gang unit, the repeal of the city’s ban on facial recognition surveillance and the attempt to end the federal consent decree over the New Orleans Police Department (NOPD). Such moves coincide with incarcerated people protesting inhumane conditions at the jail under New Orleans’s new “progressive” sheriff, and District Attorney Jason Williams going back on his campaign promise not to try juveniles as adults.

Continuing this pattern, Mayor Cantrell announced in August of 2022 that the city is hiring a team of New York City policing consultants — including John Linder, who served as a consultant for the NOPD in the 1990s. While Linder has long been credited by city leaders and mainstream media in helping root out police corruption and reduce crime, the actual history of the NOPD’s 1990s initiatives tells a different story. Instead of stemming a crime wave, Linder’s recommendations aided in producing New Orleans as an epicenter of mass criminalization.

The previous hiring of John Linder — then part of the Linder Maple Group — occurred during a period of high-profile reforms to the NOPD. In 1994 then-Mayor Marc Morial appointed Richard Pennington as the superintendent of the NOPD to modernize law enforcement and restore public confidence in policing to better fight on crime. At the time, concerns about rising crime were sensationalized by local news that positioned New Orleans as exceptionally violent.

Pennington enacted a series of reforms he termed the “Pennington Plan”: the creation of a Public Integrity Bureau aimed at weeding out corrupt cops; the implementation of community policing — the increased saturation of police in Black working class and poor communities; the expansion of police training on topics from interrogation techniques to customer service; and the appropriation of pay raises to all police officers.

While the named purpose of the Pennington Plan was to restore public safety in response to out-of-control crime, these reforms went hand-in-hand with Morial’s urban redevelopment aims; policing public space was deemed essential for gentrification projects. As documented in the “City of New Orleans 1995 Annual Report,” Morial sought to expand the city’s tourism economy through building a new convention center and expanding the footprint of the downtown tourism areas. In addition, Morial advocated for the privatization of public housing in the name of “revitalizing” neighborhoods through the displacement of long-term Black working-class and poor residents.

In 1996, Morial hired the Linder Maple Group to develop a five-year plan for the NOPD. The Linder Maple Group, well known as architects of the NYPD’s adoption of broken windows policing, was a strategic choice as Morial sought to remake New Orleans along the lines of Giuliani’s New York. While the NOPD had integrated aspects of broken windows policing in the first phase of the Pennington Plan, the Linder Maple Group proposed more. Following the recommendations of Linder Maple, the NOPD increased patrols in the French Quarter and the adjacent Downtown Development District along with the adoption of zero tolerance for “quality of life” offenses to visibly mark that the city was clamping down on disorder.

In addition, the NOPD adopted CompStat, which used statistics to track complaints and arrests by geographic policing districts to identify concentrated “hot spots” to hold district commanders to quantitative policing goals — incentivizing higher arrest rates. CompStat’s adoption was coupled with the NOPD de-prioritizing response to 911 calls. Finally, in a 1996 press conference Pennington announced his plan to implement a recruitment campaign to increase the NOPD from 1,285 to 1,700 cops.

Following these initiatives, Morial and Pennington were widely heralded by writers in the Chicago Tribune, the Washington Post, and beyond for the professionalization of the NOPD and the city’s triumph over crime. Yet against the claims made by city boosters, these policing policies impacts on crime rates were more than uneven.

Like elsewhere in the U.S., New Orleans was already experiencing a general crime decline prior to the election of Morial. While homicides did experience a notable decline after 1995 (before the hiring of Linder Maple), overall offenses labeled “violent crime” and those labeled “property crime” by the NOPD were on a significant downward trend as early as 1990, according to data provided by the City of New Orleans. Furthermore, there was little to no significant correlation between implementing broken windows and community policing tactics on the city’s drop in crime. Indeed, as political science scholar Kevin A. Unter has documented, it was more likely violence would go up rather than drop following the increase in officers and the implementation of CompStat. And against the liberal notion that professionalizing police could end the endemic racial violence of policing, New Orleanians continued to experience police corruption and abuse, as evidenced by dozens of letters to elected officials in the late 1990s and early 2000s that I reviewed while doing archival research.

Under these policies, New Orleans’s arrest rates skyrocketed. Municipal arrests jumped from 20,000 to almost 35,000, traffic arrests jumped from 4,500 to 11,00, and drug arrests jumped from just under 4,000 to over 7,000 between 1994 and 1998, according to Unter’s doctoral research. Juvenile arrests climbed from just under 3,000 in 1993 to almost 10,000 in 1998. With this continual surge of people into the criminal legal system, 1998 marked the year that Louisiana became the state with the highest per capita rate of incarceration in the United States.

Counter to the assumptions made by Democratic leaders swept up in the current wave of law-and-order nostalgia, the return of 1990s-era policing practices will not make our cities safer but it will heighten arrests and incarceration. Investing in state violence will not end interpersonal violence. It will sow disorder and instability for countless people.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. We have hours left to raise the $12,0000 still needed to ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.