Part of the Series

The Road to Abolition

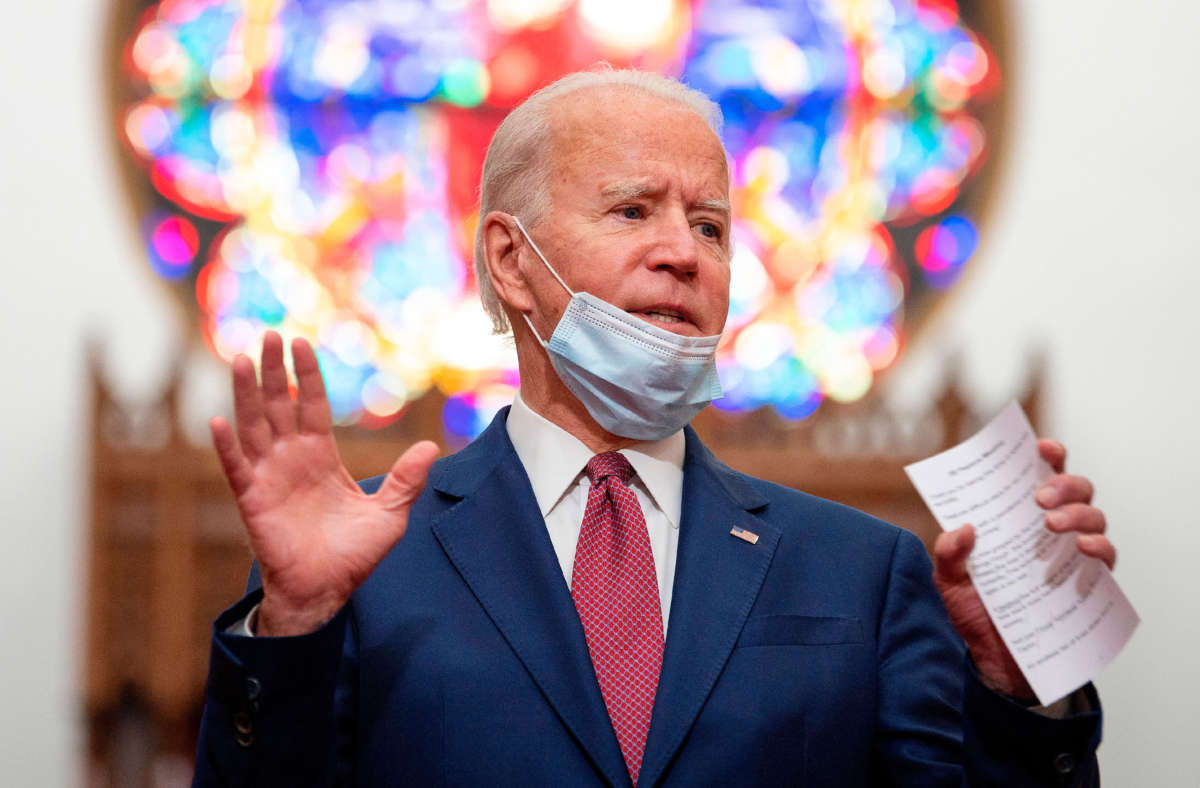

Facing attacks from President Trump, Joe Biden’s campaign said on Monday that the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee would not answer the call from hundreds of thousands of people who have taken to the streets to defund local police departments. However, most local police departments are run by city governments, and momentum toward abolishing policing as we know it today is building at the local level.

Instead of slashing federal funding for local cops, Biden and Democrats in Congress have proposed a slate of federal policing reforms that activists and civil rights groups say are modest but necessary in some cases, although certain measures could potentially provide cops with more federal funding, not less. Democratic leadership appears wary of a Trump-fueled culture war over policing erupting ahead of the 2020 elections, leaving the job of reimaging public safety up to activists and city governments that have grappled with the issue of racist and violent policing for years.

Calls to abolish and defund the police departments so resources can be redirected toward public services aimed at addressing the underlying causes of violence and harm in society are central to the protests sparked by the killing of George Floyd by a white police officer in Minneapolis. In the two weeks since Floyd’s death, uprisings and mass demonstrations erupted across the United States and beyond, lifting long-standing calls to abolish the police into the mainstream political conversation.

Backed by the Trump administration, police in several cities responded to protesters with anger and attempted to squash a popular rebellion by sowing chaos and violence. Demonstrations are expected to continue nationwide.

On Sunday, a veto-proof majority of Minneapolis City Council pledged to “dismantle” the local police department at the center of a brutal, military-style crackdown on the youth-driven uprising that shook the city after Floyd’s brutal killing. Incremental reforms have failed, the council members said, and police funding should be funneled into nonviolent public safety programs. Other cities are also currently considering cuts to police budgets.

While it will likely require a city-wide vote to abolish the police in Minneapolis, proposals for the public safety programs that would replace them will likely take shape in the coming months with input from the abolitionist activists and community groups that have taken the lead in the wake of the uprising. The shift in tone from “reform” to “dismantle” among city leaders in Minneapolis is a reminder that the movement to defund and abolish the police can make significant gains at the local level, where policymakers are closest to their constituents and the political debate can be shaped by the actual needs of individual communities.

“It shouldn’t have taken so much death to get us here,” said Kandace Montgomery, director of the Minneapolis police abolition group Black Visions Collective, in a statement on Sunday. “George Floyd should not have been murdered for so many people to wake up. It shouldn’t have taken young Black folks risking their lives in these streets, over and over.”

Meanwhile, Trump and the right have gone on the attack, attempting to tie the movement to abolish police to Biden and the Democratic Party, and stoking fears that defunding cops would put public safety at risk. Meanwhile, abolitionists argue the cops are a threat to public safety, as police harassment in communities of color and killings of unarmed Black people so clearly illustrate. Our current systems of policing and mass incarceration make society more violent, not less.

As Trump attempts to turn the slogan “defund the police” into an election-year wedge issue, Biden’s campaign said on Monday that the former vice president does not support defunding the police but does support certain criminal legal reforms and funding for “community policing,” the idea the police should build relationships with the people who live in areas they patrol.

Democrats in Congress also unveiled the Justice in Policing Act, legislation that would ban chokeholds and other violent police tactics at the federal level, and implement data collection and legal reforms aimed at making it easier to prosecute or otherwise hold police accountable for discrimination and violence. While the legislation would limit transfers of military-grade equipment to local police, it would also provide new funding for “law enforcement development and training programs” that could allow local departments access to additional federal funds.

National civil rights groups provided insights behind the Democratic bill and pledged to push for improvements as it moves forward “to ensure that real and meaningful change is achieved,” according to a statement from civil rights leaders. In recent years, some progressive Democrats have embraced additional criminal legal reforms such as abolishing cash bail and decriminalizing drugs in order to reduce police violence and incarceration.

Christy E. Lopez, the co-director of Georgetown Law School’s Innovative Policing Program, wrote in a Washington Post op-ed that there is an immediate need for some of the reforms offered by Democrats, such as outlawing no-knock warrants and training police to respond to mental health crises. However, Lopez said activists should work on “parallel tracks” and push for such reforms while working to defund and ultimately replace police departments with programs that promote public safety and restore communities that police have harmed. People are being harmed right now, and immediate reforms are needed to end the violence.

“More fundamentally, we must continue with reforms because abolition doesn’t go far enough,” Lopez writes. “Policing didn’t invent America’s institutionalized racism, social inequity or stereotyped masculinity: Policing harms are a product of these broader pathologies. If we were to get rid of policing tomorrow, those pathologies would remain.”

As we are seeing in Minneapolis and cities across the country, this work must be done at the local and movement level, particularly now that leading Democrats are clearly avoiding the abolitionist path. Abolitionists argue that attempts at reforming the police have already failed and create new opporuntities to surveil, police and incarcerate people living on the margins. Instead of reforming police, abolitionists say, we must pull their funding, repeal laws that criminalize people and give communities the resources they need to thrive.

“We believe in a world where there are zero police murders because there are zero police, not because police are better trained or better regulated — indeed, history has shown that ending police violence through more training or regulations is impossible,” the abolitionist group 8 To Abolition said in a statement this week.

Under pressure from activists, cities from New Orleans to San Francisco have adopted or considered some reforms aimed at reducing jail populations and improving relationships between residents and police. Under the Obama administration, federal consent decrees attempted to hold local cops accountable for civil rights violations and change their ways. Unfortunately, these efforts have not put an end to racist policing and violence, and now the anger and frustration is becoming sustained energy for transformation.

“Minneapolis, we are here to make history,” said Miski Noor of Black Visions Collective in a statement. “We are here to rebuild our city on a different foundation — a foundation of real safety, protection for Black people, for Native people, for immigrants, for queer and trans people, for poor people, for disabled people.”

This story has been updated with a statement from 8 To Abolition.

Truthout Is Preparing to Meet Trump’s Agenda With Resistance at Every Turn

Dear Truthout Community,

If you feel rage, despondency, confusion and deep fear today, you are not alone. We’re feeling it too. We are heartsick. Facing down Trump’s fascist agenda, we are desperately worried about the most vulnerable people among us, including our loved ones and everyone in the Truthout community, and our minds are racing a million miles a minute to try to map out all that needs to be done.

We must give ourselves space to grieve and feel our fear, feel our rage, and keep in the forefront of our mind the stark truth that millions of real human lives are on the line. And simultaneously, we’ve got to get to work, take stock of our resources, and prepare to throw ourselves full force into the movement.

Journalism is a linchpin of that movement. Even as we are reeling, we’re summoning up all the energy we can to face down what’s coming, because we know that one of the sharpest weapons against fascism is publishing the truth.

There are many terrifying planks to the Trump agenda, and we plan to devote ourselves to reporting thoroughly on each one and, crucially, covering the movements resisting them. We also recognize that Trump is a dire threat to journalism itself, and that we must take this seriously from the outset.

Last week, the four of us sat down to have some hard but necessary conversations about Truthout under a Trump presidency. How would we defend our publication from an avalanche of far right lawsuits that seek to bankrupt us? How would we keep our reporters safe if they need to cover outbreaks of political violence, or if they are targeted by authorities? How will we urgently produce the practical analysis, tools and movement coverage that you need right now — breaking through our normal routines to meet a terrifying moment in ways that best serve you?

It will be a tough, scary four years to produce social justice-driven journalism. We need to deliver news, strategy, liberatory ideas, tools and movement-sparking solutions with a force that we never have had to before. And at the same time, we desperately need to protect our ability to do so.

We know this is such a painful moment and donations may understandably be the last thing on your mind. But we must ask for your support, which is needed in a new and urgent way.

We promise we will kick into an even higher gear to give you truthful news that cuts against the disinformation and vitriol and hate and violence. We promise to publish analyses that will serve the needs of the movements we all rely on to survive the next four years, and even build for the future. We promise to be responsive, to recognize you as members of our community with a vital stake and voice in this work.

Please dig deep if you can, but a donation of any amount will be a truly meaningful and tangible action in this cataclysmic historical moment.

We’re with you. Let’s do all we can to move forward together.

With love, rage, and solidarity,

Maya, Negin, Saima, and Ziggy