In January, I am ordinarily making lemon curd, lemonade, lemon bars, lemon salad dressing and every citrus-infused dish I can think of. It is the time of year when my decades-old dwarf lemon tree is overflowing with intoxicating Meyer lemons, hanging on spiky branches like yellow baubles on a Christmas tree, heavy and sweet with juice and zest.

But this year my lemons are covered in a layer of soot and ash from the Eaton fires that began a few miles from my North Pasadena home, in neighboring Altadena, on January 7. The fire decimated thousands of acres of land and homes, 17 souls and counting, and the worldly possessions of ordinary people.

I obsessively check the survey map of destruction that city authorities have drawn up, searching for addresses of old friends and new, to determine if their homes survived. Most did not. I check on these friends constantly, afraid I’m bothering them and also worried I’m not reaching out enough, turning to texting as a form of solidarity and love, sending them resources of free clothing, donating to their GoFundMes.

I’m one of the lucky ones. This is a mantra I recite over and over. Survivor’s guilt set in as soon as I returned from being evacuated and realized my home was spared even as homes within two blocks of me burned to the ground. My living room, the only relic of the original 100-year-old home I expanded upon, smells of smoke in spite of the incessant air purifiers humming day and night. But I have a living room to clean. My lemons are covered in soot — but I have lemons and I have a kitchen to cook in. These are problems I am grateful for.

My children wear masks outdoors — a perverse inverse of the COVID-19 pandemic when indoor spaces invoked fear of deadly infections. This visual symbol of the dystopian future Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower predicted hits far too close to home — literally. Butler is buried at Mountain View Cemetery, one mile from my barely spared home. In her 1993 novel, Butler explores a grim world spoiled by climate change and capitalism, set in summer 2024. My neighborhood book club read it last summer, wholly unaware of how close her prediction lurked in our futures.

You never expect your home and community to be the epicenter of a global disaster, where those on the outside reference your local landmarks — the ones you pass by every day — and get the pronunciation wrong as any nonlocal would.

Where the president designates a national emergency and armed National Guard forces block the entrances to streets you drive on all the time.

Where flatbed trucks extracting charred vehicles from the inner reaches of Altadena are a commonplace sight.

Where you make a mental note to pick up coffee from the low-cost grocery store near your home rather than the over-priced Whole Foods only to suddenly remember that the family-run store is now gone.

Where you mourn the loss of the new café you had just started to love, after losing your previous favorite to the economic ravages of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Where you interview people who have lost everything and it turns out those people are your actual friends and you remember their home where you attended their birthday party last year.

You never expect it. As a journalist covering climate disasters and other news, I have always been on the outside, reporting on such disasters for decades. Now I am on the inside and I am terrified — but also, I am grateful, for I have soot-covered lemons and a kitchen to cook in, and a living room smelling of smoke.

I am also scared for the future. You don’t expect disaster to strike you. And you certainly don’t expect it to strike twice in the same place. But it can and it will, because that is the reality of the climate crisis we are living through.

And I am worried about the rebuilding process as real estate developers are circling like predators, offering to pay cash for Black- and Brown-owned properties before the embers have even turned cold.

Altadena was consumed by a voracious firestorm, destroying a racially diverse community with varying incomes, a large enclave of more than 41,000 people, where nonwhite people outnumbered whites and where the median household income was $129,000 — low by Los Angeles standards.

At the same time, the Pacific Palisades also burned to ashes, a wealthy community of nearly 18,000, a population that was 82 percent white, with a median household income of $195,000.

The climate crisis doesn’t care if you have a beloved family estate in need of repairs passed from generation to generation, or a fancy McMansion. It doesn’t care if you make lemon curd from your fruit tree, or if you have a live-in chef who cooks for you with lemons from Erewhon.

We live in fear of fire, drought, flooding and heat waves. But the real culprits are the fossil fuel industry and the forces boosting them. They are disconcertingly invisible enemies whose crimes are a collective punishment borne by all of us.

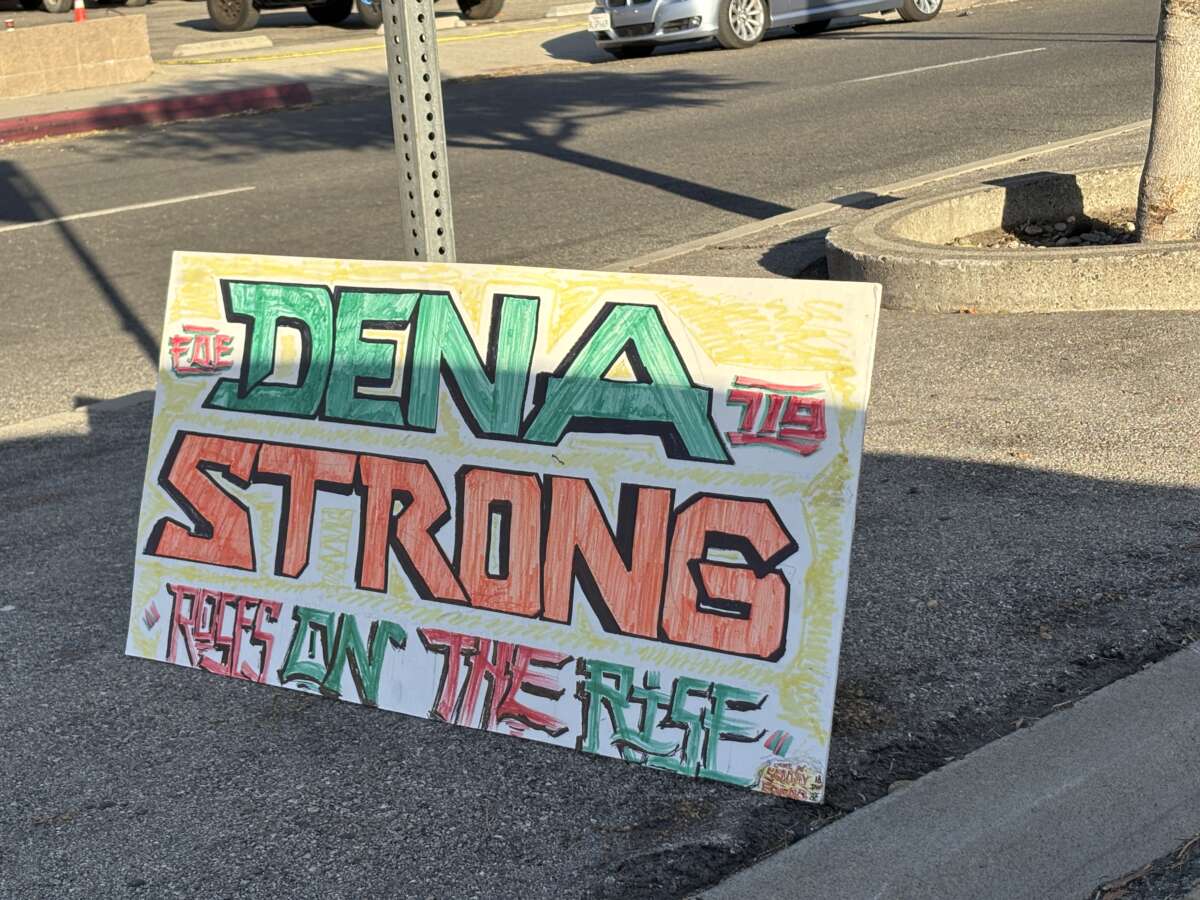

We are putting on a brave face. We are carrying signs saying, “Altadena, Not for Sale,” in an effort to retain the hallmarks of our beautifully unique community. We are organizing mutual aid hubs to care for one another. And we are proclaiming “#DenaStrong” to stave off the despair. We don’t know if insurance companies will pay out, if city authorities will be able to clean the debris in good time, if FEMA assistance will ever come through.

There is only one certainty in our future: Climate disasters will continue unless we reverse the climate crisis now.

Speaking against the authoritarian crackdown

In the midst of a nationwide attack on civil liberties, Truthout urgently needs your help.

Journalism is a critical tool in the fight against Trump and his extremist agenda. The right wing knows this — that’s why they’ve taken over many legacy media publications.

But we won’t let truth be replaced by propaganda. As the Trump administration works to silence dissent, please support nonprofit independent journalism. Truthout is almost entirely funded by individual giving, so a one-time or monthly donation goes a long way. Click below to sustain our work.