Many people are pointing to the German economy’s recent upturn as solid proof that austerity measures work.

But this is a foolish argument.

The austerity policies will not come into effect until 2011 — at the moment, economic policy is actually quite Keynesian.

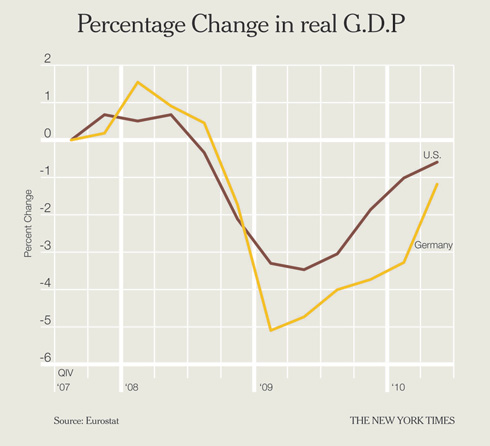

Let’s look at the German economy’s actual performance to date. The graphic on this page charts the country’s real gross domestic product over time.

Many commentators and economists have focused on the uptick at the end.

Since the economy has yet to recover to its pre-crisis G.D.P. level, I’m not willing to declare that an economic miracle has occurred.

Here’s a simplified version of the story: Germany did not experience a housing bubble, so it was not directly affected by the bust. But its economy is very export-oriented, with a focus on durable manufactured goods.

Demand for these goods plunged in the early stages of the crisis — so much that, remarkably, Germany experienced a bigger decline in G.D.P. than most of the bubble economies — but has bounced back since summer 2009.

This has pulled the German economy back up, mainly because exports to China have done especially well.

Simply put, growth has not been great for the past two years, one quarter notwithstanding. But that is not the whole story.

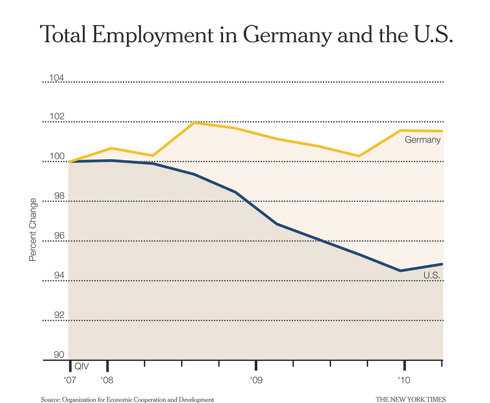

Even when the economy was slumping badly, Germany avoided the mass layoffs seen in the United States, as shown by the employment-comparison graphic at right. This is partly due to the kurzarbeit program of work-sharing — a system in which the government subsidizes most of a worker’s salary if his hours are cut.

Also, German labor laws and strong unions protect workers from being treated as variable costs, as they are in the United States.

So conservatives in the United States who are holding up Germany as a role model in the argument for immediate spending cuts are actually disparaging American-style capitalism and praising the virtues of eurosclerosis — that sickness whose symptoms include high unemployment and slow job creation in an otherwise growing economy.

Truthout is supported by our readers. Help keep us independent with a tax-deductible donation.

I’m certainly not the first to point this out. Wolfgang Munchau, a columnist for the Financial Times, noted in an Aug. 29 piece that, so far at least, Germany’s growth simply reflects recovery from an unusually deep slump: “So far, this looks like classic dead-cat bounce.”

“Germany’s economic strength is likely to be persistent, toxic and quite possibly self-defeating in the long-run,” he writes.

If there’s a slam-dunk argument for austerity here, it’s remarkably well hidden.

—————-

BACKSTORY: Looking Beyond Market Successes

Germany announced in August that its economy grew an unexpected 2.2 percent during the second quarter of 2010. This was seen by analysts as a dramatic resurgence for the euro zone’s largest economy.

Some analysts argue that this high rate of expansion cannot be sustained, pointing out that after Germany’s gross domestic product declined by 5 percent last year, the economy had more potential to grow than the economies of other euro-zone countries. When the euro’s value fell, Germany — the world’s second-largest exporter nation, behind China — benefitted from an enormous competitive advantage in the global marketplace. This was true especially in comparison to Japan, its main rival in the voracious China market, as the yen strengthened and Japanese goods became more expensive.

But the same things that helped Germany in the short term might prove to be its undoing in the long term. Prices for German goods are well below those of its euro-zone neighbors because of the government’s initiatives to moderate wages. If the global recovery takes longer than expected and external demand for German goods falters, prices could stay low for a long time.

Despite the uncertain economic outlook, consumer confidence in Germany is high and household spending is up. The markets seem less convinced, however: corporate borrowing in Germany fell 1.3 percent this past July, according to the European Central Bank, suggesting that a rebound is not yet assured. Nevertheless, Joerg Kraemer, chief economist at Commerzbank AG in Frankfurt, told Bloomberg Businessweek in August, “the German economy will reach its pre-crisis level much earlier than thought.”

Truthout has licensed this content. It may not be reproduced by any other source and is not covered by our Creative Commons license.

Paul Krugman joined The New York Times in 1999 as a columnist on the Op-Ed page and continues as a professor of economics and international affairs at Princeton University. He was awarded the Nobel in economic science in 2008.

Mr Krugman is the author or editor of 20 books and more than 200 papers in professional journals and edited volumes, including “The Return of Depression Economics” (2008) and “The Conscience of a Liberal” (2007).

Copyright 2010 The New York Times.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.