In 2006, the Brazilian government announced the discovery of oil and gas reserves in extremely deep ocean waters, beneath a layer of salt 2,000 meters thick, which they called “pre-salt” petroleum. These reserves will position Brazil to be the sixth-largest producer of petroleum in the world by 2035. The Fourth Fleet of the US Navy, inactive since after World War II, was re-established in 2008 and currently patrols the coasts of Latin America and the Caribbean, including the Brazilian coast. During his time in office, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva expressed his concern: “We are very worried. We don’t need the Fourth Fleet; what we need is for our own navy to protect our platforms and our pre-salt deposits.”

Since the end of 2014, the publicly owned Brazilian oil company Petrobras has experienced heavy criticism, beginning with an operation called Lava Jato. Lava Jato was an investigation carried out by the federal police that identified a corruption network involving certain public officials and politicians with money laundering and organized crime. Meanwhile, in the halls of power and the media, as well as in academic spaces, a fierce debate has been unleashed regarding the topic. The discourse has become polarized between those in favor of nationalization and those who defend privatization as one of the solutions to the problem. As Luiz Ferreira, an economist and professor at the University of Sao Paolo, told Truthout, “one of the efficient ways of returning the company of Petrobras back to Brazilian society is through its privatization.”

“There are powerful opposing interests at play regarding the growth of Petrobras. They are eager to take over the company, its market, its advanced technology, and its immense oil and gas reserves in Brazil.”

On the other hand, there are those who defend the company, even after the Lava Jato investigation, such as former president Lula da Silva. On February 24, 2015, a campaign was launched called “To defend Petrobras is to defend Brazil,” where a statement was presented, part of which read, “We do not have the right to be naïve at this time: There are powerful opposing interests at play regarding the growth of Petrobras. They are eager to take over the company, its market, its advanced technology, and its immense oil and gas reserves in Brazil.”

Fishermen in the community of Barra de Riacho, Espirito Santo, Brazil. December 16, 2014. (Photo: Santiago Navarro F.)

Fishermen in the community of Barra de Riacho, Espirito Santo, Brazil. December 16, 2014. (Photo: Santiago Navarro F.)

On March 13, more than 70,000 workers belonging to various unions, social organizations and supporters of the Workers Party, who voted for President Dilma Rousseff, marched through Paulista Avenue, the financial capital of Brazil. They marched in defense of petroleum and above all for pre-salt petroleum. They are defending the mandate of the president, whose reputation has been damaged by revelations of corruption in Petrobras.

Among the diverse accusations being leveled, much is spoken about people who have been corrupted, but very little has been said about the companies that also fell into corruption in order to be able to implement their projects. “We have to be tough on corruption, but also on those who do the corrupting. This is a privatization strategy,” José María Rangel told Truthout. He is the president of the Single Federation of Oil Companies, which is also part of the campaign.

“We talk about petroleum being ours. Ours? Whose? Does it belong to the Capixabas, the indigenous people of Espirito Santo, to Rio de Janeiro, to Brazil, or to the companies?”

The two discourses, however, have little resonance with ordinary people, who have received no benefit from the so-called patrimony of the Brazilian people. Beyond the two positions, there are people who think that there is a credibility crisis that extends across different political parties, from progressive ones to those on the right and even within the current government. “Now they are discussing who the thieves are in Petrobras. What sort of country is this? All those in government steal; this is left over from the dictatorship,” Pedro Costa, of the Linhares municipality in the state of Espirito Santo, told Truthout.

“So we talk about petroleum being ours. Ours? Whose? Does it belong to the Capixabas, the indigenous people of Espirito Santo, to Rio de Janeiro, to Brazil, or to the companies? It is a discourse that they are selling us, and the oil is going to be passed into the hands of multinational companies anyway and of all the companies that make up the petroleum chain of production,” said Marcelo Calazans of the Federation of Authorities for Social and Educational Assistance.

Promises of Progress in Traditional Communities

José Costa is a fisherman, beekeeper and former employee of the company Geokinetics. Degredo, Linhares, Brazil. December 18, 2014. (Photo: Santiago Navarro F.)

José Costa is a fisherman, beekeeper and former employee of the company Geokinetics. Degredo, Linhares, Brazil. December 18, 2014. (Photo: Santiago Navarro F.)

While the debate over the privatization of petroleum resources intensifies, the consequences of the rate of exploration and exploitation of new deposits fall on traditional communities, who have seen none of the benefits from oil profits.

In the Degredo community, in the municipality of Linhares, on the coast of Espirito Santo, Brazil, the intense yellow of the oil and gas pipes contrasts with the vegetation, which is made up of coconut palms, and the soft colors of the rustic houses built with sheets of metal and wood; others are made of concrete. Like arteries, the pipelines are dispersed throughout the community. In this place, once again a discourse of development and progress brought about by mining and petroleum extraction is being trotted out.

“Development never arrived; the only thing we do understand about this discourse is its tragedy.”

The majority of people in the community work cultivating coconut palms, producing honey and, above all, in small-scale fishing. They weave their own fishing nets and much of the time they build their own boats. It is not the first time they’ve heard the progress argument. Pedro Costa, a fisherman and beekeeper, tells Truthout that since he was 14 years old, in 1952, when the exploration and exploitation of petroleum first began, companies came promising development and the improvement of communities. Pedro is silent for a moment, and then in a soft voice says, “That development never arrived; the only thing we do understand about this discourse is its tragedy.”

José Costa, also a fisherman and beekeeper, wears a yellow shirt and well-worn orange pants. The shirt is from the company where he used to work, with a logo that reads Geokinetics, a multinational company with its headquarters in Houston, Texas. It offers specialized services to oil and mining industries. On its website, it boasts that it offers its services across the world, principally in the Middle East, Alaska and in the mountains and rainforests of South America, where there are petroleum and mineral resources.

A slurry pipeline belonging to the Samarco company that runs to the ocean, in the community of Anchiete, Espirito Santo, Brazil. December 20, 2014. (Photo: Santiago Navarro F.)

A slurry pipeline belonging to the Samarco company that runs to the ocean, in the community of Anchiete, Espirito Santo, Brazil. December 20, 2014. (Photo: Santiago Navarro F.)

One of the services that Geokinetics offers is the acquisition and interpretation of seismic data on land and in water. It uses geophysical technology, specifically reflection seismic exploration, which uses electric currents in compressed air or detonations of explosives. Seismic waves are shot toward the depths of the sea, which travel at speeds that allow geologists to determine which layers they have to drill through and at what depth so that they can extract the petroleum. In Brazil, Geokinetics is one of the companies that is investigating unconventional petroleum, known as pre-salt.

Pre-salt comprises an enormous area of petroleum reserves, 7,000 meters below sea level in Brazil. The deposits are located between the states of Santa Catarina and Espirito Santo.

According to data from Petrobras from 2010 to 2014, the daily average production of pre-salt grew almost 12-fold, increasing from an average of 42,000 barrels per day in 2010 to 739,500 barrels per day in 2014. According to a US Energy Information Administration report from 2013, Brazil is destined to become the sixth-largest producer of petroleum and one of the world leaders in energy production, reaching almost 6 million barrels per day by 2035, supposing a 30 percent net increase in global oil production.

This exploration method is killing fish and diverse marine species that depend on sonar for communication.

“Although pre-salt oil exploration began in 2010 here in the state of Espirito Santo, the impacts have been felt since the 1990s. The exploitation of petroleum already existed here, but it wasn’t as intense as it is today with pre-salt. The impacts started before the installation of the platforms; they used explosives with a ‘seismic’ method,” said José dos Santos, the president of the Federation of Fishermen and Fish Farmers’ Associations of Espirito Santo.

Santos assures that this exploration method is killing fish and diverse marine species that depend on sonar for communication. “The researchers never gave us an answer of whether or not it kills fish, but we are certain that it does, and that it will affect communities,” Santos told Truthout.

According to the “Report on the Principal Impacts of Ocean Oil Exploration,” published in 2012 by the Institute of Workers’ Unions, the Environment and Health, the most common methods used by seismic acquisition operations usually generate sound levels of between 215 and 230 decibels, with frequencies between 10 and 300 hertz. The scientific community has adopted 180 decibels as the level beyond which irreversible physiological damage is seen in cetacean marine mammals, which include species of dolphins and whales that use sonar for communication. In terms of the capacity of the human auditory system, exposure of 120 decibels can cause total hearing loss.

The Tip of the Iceberg

A protest in defense of the company Petrobras, with a sign that reads: “Stop using Petrobras – corruption – to justify the coup.” March 13, 2014. (Photo: Santiago Navarro F.)

A protest in defense of the company Petrobras, with a sign that reads: “Stop using Petrobras – corruption – to justify the coup.” March 13, 2014. (Photo: Santiago Navarro F.)

Seismic exploration is just the tip of the iceberg in terms of the implications of the extraction of pre-salt petroleum. In the coastal zone of Espirito Santo alone, three dozen megaprojects have been planned. This exploitation requires the involvement of a number of public or private enterprises, ranging from those who do environmental impact studies to radioactive waste control, electrical infrastructure, highways, drainage systems, storage, and above all, land and sea transport.

“Imagine that the coast of Espirito Santo, which is relatively short, only 400 kilometers long, ends up receiving many different venture projects. There are 30 megaprojects. There is an impact from each of those, but there is also a global impact,” said researcher Cristiana Losekann, author of Environmentalists in Movement in Brazil.

“The traffic alone from the ships is already generating a surprising amount of pollution in the ports and for the marine environment.”

The flow of ships in the 30 ports could be more than 3,000 vessels per month. “Can you imagine the movement of 100 to 200 boats – in each port – depending on the cargo, coming and going? Then you multiply that by 30, according to the envisioned growth in cargo and volume that has been presented. What will that growth be like?” said Ernani Pereira, the president of the Port Workers Union. “The hypocrisy must stop, and it has to be said – the traffic alone from the ships is already generating a surprising amount of pollution in the ports and for the marine environment.”

Community of Barra de Riacho, municipality of Aracruz, Brazil, which has been impacted by the pulp industry and now by pre-salt petroleum. December 16, 2014. (Photo: Santiago Navarro F.)

Community of Barra de Riacho, municipality of Aracruz, Brazil, which has been impacted by the pulp industry and now by pre-salt petroleum. December 16, 2014. (Photo: Santiago Navarro F.)

Daniela Mirelles from the NGO FASE tells Truthout that a wide range of companies are arriving in the state and apparently are working with projects not directly connected to pre-salt petroleum. “What’s happening is that the oil and gas resources are so large that they are activating a chain of production that revolves around the pre-salt,” Mirelles said. “Some examples of this are the steel industry, land and maritime transportation, and companies that produce specialized equipment.”

Another Port: Manabi

A fisherman who is over 70 years old in the community of Barra de Riacho, Aracruz, Brazil. December 16, 2014. (Photo: Santiago Navarro F.)

A fisherman who is over 70 years old in the community of Barra de Riacho, Aracruz, Brazil. December 16, 2014. (Photo: Santiago Navarro F.)

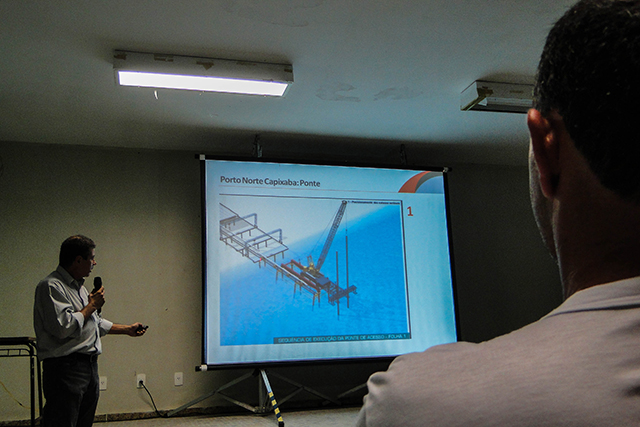

To give another example of the scope of these projects, in the municipality of Linhares, in the community of Degredo, the construction of a port called the Northern Port of Capixaba has been projected. It will be for offshore operations and would cover an area of 597 hectares along six kilometers of the community’s coastline.

According to information obtained by Truthout in a presentation given in December 2014 by the Manabi company, which is responsible for the port project, a support structure will be built around the port. It will include an industrial area, electricity transmission lines, highways and railways, which will attract new investments in other projects.

“And afterward when all the petroleum and minerals run out, what will be left for us?”

Manabi, which considers itself one of the biggest mining companies in the world, was just created in 2011, with an investment of $850 million. Of this, 11.5 percent comes from the US corporation EIG Global Energy Partners, 17.8 percent from the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan, 17.3 percent from the Korea Investment Corporation, 14.7 percent from Fabrica Holding S.A., 9.7 percent from Southeastern Asset Management, and 29 percent from other companies. The principal objective of this company, apart from construction of the port, is the construction of a mining pipeline, where 25 million tons of high-quality iron ore would be transported annually, destined for export to different parts of the world.

In order for the iron ore to reach the Northern Port of Capixaba in Linhares, the mining pipeline system will have to cover 511 kilometers, crossing 23 municipalities. It will leave from the municipality of Morro del Pilar, where iron reserves are already being mined in the state of Minas Gerais, and will end up in Linhares, in Espirito Santo.

The production capacity of this mine is projected to be a little over two decades of exploitation, according to the technical report by SRK Consulting, an independent international consulting group and leader in the world market of certifying mineral and petroleum reserves.

According to the SRK Consulting report, the certified reserves in Morro del Pilar have been found to be 1.3 billion tons of measured resources and 312 million additional estimated tons.

The Manabi company covers the three parts of the megaproject under three different names: Manabi Logistics S.A. for the Northern Port of Capixaba, Dutovias of Brazil S.A. for the construction of the mining pipelines, and Morro do Pilar Minerals S.A. for the exploitation of iron ore.

“Fishing is an autonomous way of life in these communities, which respect the natural world. If these projects continue to advance, the fishermen will disappear and there will be no going back.”

“And afterward when all the petroleum and minerals run out, what will be left for us?” asked one of the fishermen who attended the presentation of the project given by Manabi. The answer from the port pre-operations manager, Romeu Rodriguez, who was visibly annoyed at the number of questions being asked, was the following: “The project will be developed in a way that is favorable to coastal communities. They will have jobs so they will be able to buy more fish. There are also workshops offered by the company, or projects, such as an ice factory and professional training for fishermen,” Rodriguez said.

In response to this same question, Alexandre Pasolini, a project manager for the company Econservation, who is responsible for the development of the environmental impact studies for the project (in Brazil these studies are paid for by the company who will be undertaking the project), said, “the compensation may come in the teaching of other fishing techniques; the port might even be attractive to the fish.” Both answers were met with jeers from the audience.

City of Victoria, Espirito Santo, Brazil – the epicenter of ships carrying raw materials destined for export. December 23, 2014. (Photo: Santiago Navarro F.)

City of Victoria, Espirito Santo, Brazil – the epicenter of ships carrying raw materials destined for export. December 23, 2014. (Photo: Santiago Navarro F.)

The impact is not just on marine ecosystems; the communities that live by and depend on the sea are directly affected as well. According to the Second Statistical Bulletin of Fishing and Aquaculture in Brazil, published in 2010, there are 16,455 registered fishermen and women who work in the state of Espirito Santo. Of that number, 9,226 are men and 7,229 are women, a population which could not be absorbed by the companies, who do not accept workers older than 30. Of that number, only a small percentage would be women, and only those with required levels of academic study would be hired, according to the Manabi sustainability report from 2013. “The positions are designated for youth between 18 and 30 years old. The companies will give courses for professional fishermen and carpentry classes so they can work on the ships and in the manufacture of motors for ships as well,” said the presenters from Manabi.

Researcher Simome Raquel Batista, from the Federal University of Espirito Santo, who has opposed with other researchers the implementation of these projects, told Truthout, “Fishing is an autonomous way of life in these communities, which respect the natural world. This is where the danger lies. It is a land dispute. I was just in communities that were devastated by the Super Port of Acu, in Rio de Janeiro. The materials being shipped from the port are iron and steel, petroleum, coal, granite, metal wastes, iron ore and general cargo. If these projects continue to advance, the fishermen will disappear and there will be no going back.”

Maximum Exploitation of Petroleum

Paulista Avenue, in the financial center of Sao Paulo, was filled for miles with workers from different unions, such as the Main Workers Headquarters and the Workers Party, who marched in defense of President Dilma Rousseff. March 13, 2015. (Photo: Santiago Navarro F.)

Paulista Avenue, in the financial center of Sao Paulo, was filled for miles with workers from different unions, such as the Main Workers Headquarters and the Workers Party, who marched in defense of President Dilma Rousseff. March 13, 2015. (Photo: Santiago Navarro F.)

“Petroleum is not just any merchandise in the capitalist system. It is the backbone of the capitalist system,” said Marcelo Calazans, who together with other organizations has promoted activities and initiatives such as the so-called “petroleum-free areas.”

“The question is not to look for an alternative to oil; the question is to search for an alternative to an oil society.”

“Petroleum is present in our everyday life, in our food, our clothes, in our cell phones. In a way, it represents the lifeblood of the market and, above all, in the longed-for dream of half the world to acquire products such as cars.”

“What exactly do we need petroleum for? Why such high levels of consumption? These questions are not asked. Everything starts with the assumption that production must expand, and even beyond this, that it must grow at an incredible rate, until it reaches its capacity,” Calazans told Truthout.

“Reducing the rate of expansion or diminishing the scope of that expansion is an important strategic aspect of the current struggles – for the struggle of people for their territories. Because these are fights for survival,” Calazans added. “Those territories are going to disappear.”

Territories of Utopia

Oil well between the communities of Degredo and Regencia, Linhares, Espirito Santo, Brazil. December 18, 2014. (Santiago Navarro F.)

Oil well between the communities of Degredo and Regencia, Linhares, Espirito Santo, Brazil. December 18, 2014. (Santiago Navarro F.)

Marcelo Calazans does not put much stock in economic growth, in development, in modernity. He even talks about a reduction in economic activity. “We have seen that the GDP of countries does not necessarily reflect the happiness levels of people. I am in agreement with the people who propose a slowing of economic growth,” he said.

If we continue at this rate of what is known as economic growth, it will be impossible to go back, according to Calazans. “It is said: We have to look for alternatives to oil. Nuclear energy, wind, solar, whatever. The question is not to look for an alternative to oil; the question is to search for an alternative to an oil society. It is not about substituting for the oil itself; it’s about changing the patterns of society, this consumerist dream.”

A manager from Manabi gives a presentation to local fishermen about the mining pipeline project and the North Capixaba port. (Photo:Santiago Navarro F.)

A manager from Manabi gives a presentation to local fishermen about the mining pipeline project and the North Capixaba port. (Photo:Santiago Navarro F.)

Calazans speaks about the importance of preserving memory. “What is going to remain of the land for future societies? We have to prepare ourselves because this industrial consumer society will reach its limit. We have to prepare ourselves and protect these utopian territories because it is through them that we will be able to recover new values.”