Support justice-driven, accurate and transparent news — make a quick donation to Truthout today!

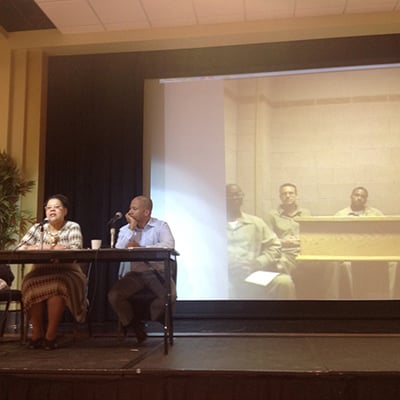

Formerly incarcerated advocates Vivian Nixon and Glenn Martin speak at the National Conference on Higher Education in Prison in Pittsburgh, November 6. (Photo: Jean Trounstine)This story could not have been published without the support of readers like you. Click here to make a tax-deductible donation to Truthout and fund more stories like it!

Formerly incarcerated advocates Vivian Nixon and Glenn Martin speak at the National Conference on Higher Education in Prison in Pittsburgh, November 6. (Photo: Jean Trounstine)This story could not have been published without the support of readers like you. Click here to make a tax-deductible donation to Truthout and fund more stories like it!

The US Department of Education announced on July 31 that as part of President Obama’s initiative to reduce mass incarceration, the country would reinvest in higher education in prison. It announced the Second Chance Pell Pilot Program to allow a select number of incarcerated Americans to pursue higher education with the expressed goals of “helping them get jobs, support their families, and turn their lives around.” According to John Linton, former director of the Office of Correctional Education at the Department of Education, who spoke at the recent National Conference on Higher Education in Prison, he’d heard from colleagues that more than 200 institutions of higher education had responded with letters of application. Once college programs are approved, their students will be funded by Pell grants – a form of federal financial aid for postsecondary education programs.

The cry to get rid of prisoner Pell grants came mostly from the old Confederacy.

While this is extremely good news, prisoners and formerly incarcerated people have been speaking out for years about wanting education for all. Prisoners and those formerly incarcerated have historically been at the forefront of advocating for prisoner education. They renounced the demise of funding and the elimination of college programs in 1994, and have continued to fight to get college classes returned to those inside. They have publicized the difficulties that formerly incarcerated people face in obtaining higher education. They have been key voices in vocalizing how education strengthens students to lead in the fight to decarcerate our prisons and jails.

Now that there is finally national momentum to expand college education for prisoners, these pioneers should again be held as the beacon to help light our way. We need to listen to their voices if we are to make sound policy. The message coming through loud and clear is that we need to support the Second Chance Pell Pilots but also to go much further: We need to both help students continue their education when they leave prison and to pass the Restoring Education and Learning (REAL) Act, returning education to all.

Christopher Zoukis, an incarcerated writer and advocate, said in an email, “The research on prison education is clear: With each additional level of education obtained, the rate of recidivism drops correspondingly. But … the real story here is that education opens doors and minds.”

The REAL Act was introduced in May 2015 by Rep. Donna F. Edwards (D-Maryland) to ensure state and federal prisoners will be once again eligible for Pell grants. Forty-four congressional co-sponsors had signed on as of July 31. It also is backed by numerous organizations such as the American Civil Liberties Union, Correctional Education Association, Drug Policy Alliance and the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund.

History of Pell Grants Behind Bars

Between 1972 and 1994, there was a strong college prison program across the United States. The grant program was originally a retooling of President Lyndon Johnson’s Higher Education Act, and it was initiated by Sen. Claiborne Pell in order to make college education accessible for all who were eligible.

Historically, 99 percent of Pells went to students outside prison and under 1 percent went to prisoners who had earned a GED or graduated from high school; student prisoners could apply for Pell grants as long as they were not sentenced to death or to life without parole; politics is always in play when money is involved. Still, more than 60 percent of medium- and maximum-security prisons had such funded college programs in the 1980s. Many programs flourished with little money.

One of the first incarcerated students to analyze why Pells were taken away from prisoners was Jon Marc Taylor, who earned his Ph.D. behind bars in Missouri. Taylor received the Robert F. Kennedy and The Nation/I.F. Stone Journalism Awards for his reporting on “Pell Grants for Prisoners: Why Should We Care.” In that article, Taylor pointed out that the cry to get rid of prisoner Pells came mostly from the old Confederacy, and that it was altogether false that prisoners were depriving other low-income, free-world students from receiving Pells.

“Education on the inside builds leaders who have a sophisticated understanding of the network of incarceration.”

However, in spite of advocacy, including Taylor’s op-ed in The New York Times, in which he pointed out that college significantly reduced prisoners reincarceration, President Bill Clinton signed into law the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 – an act he has since acknowledged made mass incarceration worse. Taylor said it had a “plethora of draconian measures,” including amendments that resulted in the elimination of Pells for prisoners, hastening the decimation of more than 50 percent of college programs behind bars.

Taylor continued to advocate from a prison cell through his writing, educating those on the outside about the need to reinstate Pells. He pointed out that college-educated prisoners were more likely to get jobs, and prisoner education is in society’s best interest “criminologically, economically, penalogically and socially.” He inspired those on the inside to further their knowledge with his book, first published in 2002, and now in its third edition, Prisoner’s Guerrilla Handbook to Correspondence Programs in the United States and Canada.

Since then, one prisoner who has taken up the mantle is Christopher Zoukis. Zoukis wrote College for Convicts: The Case for Higher Education in American Prisons in 2014. His book followed on the heels of a 2013 report from the RAND Corporation, which spelled out how incarcerated individuals who participated in correctional education were 43 percent less likely to return to prison within three years than prisoners who didn’t participate in any correctional education programs. Zoukis still advocates for college programs, which currently aren’t offered in the federal system in which he is incarcerated. Besides three other books, he has also written numerous articles, including one in 2015 urging the return of Pell grants. He wrote, “Prison education is on the federal legislative agenda in a way not seen since the mid-1990s, and for prisoners and their supporters that provides renewed hope.”

In an email, Zoukis told Truthout, “As [prisoners] succeed, or merely attempt to succeed (whether by taking courses in prison or applying for jobs), even their children and those around them seem to become inclined to buy into their path and the possibility that perhaps they too could live a better life. In this regard, prison education, regardless of the level, serves as a mechanism for stopping repeat crime and the intergenerational cycle of crime that is so prevalent today.”

Continuing the Fight

Since the ban on Pells, some in-prison higher education programs have sprung up. Programs such as the Bard Prison Initiative (which beat Harvard this year in that famous debate), the Education Justice Project in Illinois, the Goucher Prison Education Partnership and the Cornell University Prison Education Program are a few well-known ones connected with competitive colleges. A map of these programs shows that there are more than 80 across the United States. While these programs are great, they are privately funded, some by the universities, and therefore few and far between, compared to the 350 programs that existed in prisons and jails years ago. Formerly incarcerated people want education to help them build a movement.

When Glenn E. Martin went to prison in 1994, Pells had just been eliminated in most of New York’s prisons. In an interview, he said that he was at the lowest point in his life when a correctional counselor suggested he go to college. He thought it was a joke, at the time. However, he had ended up in the Wyoming Correctional Facility in Attica, a prison that had one of the last existing college programs in the state. There were far fewer students enrolled, around 35, in contrast to a few hundred who had taken classes at that prison during the heyday of Pells. Martin began taking classes that helped him better understand his own trajectory and its context in the world.

“When I watched a film of the Holocaust, I had a moment,” he said. “I realized that other people have their own atrocities.”

He earned a two-year liberal arts degree behind bars. When he got out, he found out about Pell grants and began doing advocacy work with Dallas Pell, Sen. Claiborne Pell’s daughter, in 2003, in order to try to get Pells reinstated behind bars. He is currently enrolled in graduate studies.

The REAL Act is important, says Martin, because “many of the strongest leaders outside benefited from education inside. Education on the inside builds leaders who have a sophisticated understanding of the network of incarceration. With education, they also have a historical perspective and context, which allow them to approach decarceration campaigns and gives them a broader analysis of mass incarceration and systematic racism.”

Prisoners who have the benefit of college education also decrease reliance on public assistance, increase their employment rates, improve their physical and mental health, and elevate the quality of life for their children.

Building a Coalition

A few years later, Martin and another formerly incarcerated advocate, Vivian Nixon, created the Education from the Inside Out Coalition, which is committed to removing barriers to higher education for formerly incarcerated people (such as questions about criminal background on college and employment applications).

Nixon is also the executive director of College and Community Fellowship, an organization committed to women with criminal record histories and their families. College and Community Fellowship advocates to return Pell grants to college programs, and Nixon believes strongly in the REAL Act as a way to empower people behind bars. In a listserv on higher education in prison, she wrote: “My response is to work with the system that we have and try to change it by educating those most marginalized by the system to be involved in the political process. This requires making sure they are in a position to be involved. People who are struggling for basic survival have less capacity to organize and fight oppressive systems.”

Martin concurred: “Any level of access is important because education is a huge self-esteem builder and it reminds people they do have value. People on their way out create a seamless bridge for others and a community to land in.”

In an interview, Nixon said that, ideally, we must think about significantly decreasing the number of people behind bars. Instead of incarcerating 2.2 million people, she said, “We need to provide many of them with trauma counseling, and help them with job resources and family involvement.” Nixon pointed out that decarceration goes hand and hand with education.

“If we focus on correcting problems in our public schools, where people are living in communities, focus on education and keep people out of the school-to-prison pipeline, we can attend to under-resourced schools in neighborhoods where the majority of people who go to prison come from,” Nixon said. “Education is a core pillar that works both on the front and back end.”

Holding Trump accountable for his illegal war on Iran

The devastating American and Israeli attacks have killed hundreds of Iranians, and the death toll continues to rise.

As independent media, what we do next matters a lot. It’s up to us to report the truth, demand accountability, and reckon with the consequences of U.S. militarism at this cataclysmic historical moment.

Trump may be an authoritarian, but he is not entirely invulnerable, nor are the elected officials who have given him pass after pass. We cannot let him believe for a second longer that he can get away with something this wildly illegal or recklessly dangerous without accountability.

We ask for your support as we carry out our media resistance to unchecked militarism. Please make a tax-deductible one-time or monthly donation to Truthout.