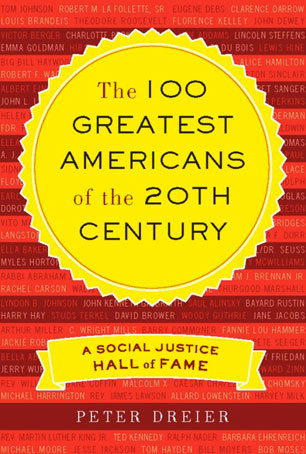

Peter Dreier’s “The 100 Greatest Americans of the 20th Century: A Social Justice Hall of Fame” forces reflection on greatness, the vast progress and reaction of 20th century history and who we will consider great when looking back on the present.

What makes a person a “great” American? The question lies at the heart of the book, The 100 Greatest Americans of the 20th Century. According to author Peter Dreier, a “great” individual displays a “commitment to social justice and a record of accomplishment, of using his or her talents to help achieve important progressive change.”

Dreier’s “greatest” include “organizers and activists who mobilized or led grassroots movements for democracy and equality.” Also included are “writers, musicians, artists, editors, scientists, lawyers, athletes and intellectuals who challenged prevailing ideas and inspired Americans to believe a better society was possible.” Finally, politicians who “gave voice to social justice movements in the corridors of power and translated their concerns into new laws that changed society” also merited inclusion.

Using those guidelines, and what seems to be his near-encyclopedic knowledge of the history of 20th-century political and social movements, Dreier lays out his choices in 100 short, provocative biographical essays ordered chronologically by their subject’s date of birth. Those essays are framed by his carefully crafted introduction, in which he explains his criteria and provides context for his survey. While the book examines individuals, it’s really also a history of political movements, or what Dreier calls a “mosaic of movements.” He never lets the reader forget that while his “greatest” Americans played notable roles, countless other nameless individuals provided the heart and soul for progressive movements for change.

Rather than government benevolence or initiative, those movements (and the outside pressures they created) have always been at the heart of new policies and social progress. Dreier’s “progressives” have been both outsiders and insiders. Many were instrumental to grassroots movements for peace, disarmament, civil liberties, labor rights, environmental protection, and racial, sexual and gender equality. Others worked inside government to lead the changes pushed upon authorities by outside forces.

Dreier’s book is a fascinating read. It can be read chronologically or just as easily by picking and choosing the individuals whose life and work he examines. Some names are familiar, yet with those Dreier seemingly always adds something new – things beyond the conventional wisdom. How many people know, for example, that before he died Martin Luther King Jr.’s despair about US capitalism led him to endorse democratic socialism? Who knew that Theodor Geisel (a k a Dr. Seuss) wasn’t merely a children’s book author but also a progressive crusader against racism, nuclear arms and environmental destruction?

Others among Dreier’s “greatest” are relatively, if not completely, unknown. In those cases, we learn even more. We discover, for example, physician Alice Hamilton’s pioneering work for occupational health and safety. Or we learn about Floyd Olson’s neglected contribution to the Farmer-Labor Party and its progressive alliance of rural farmers and urban workers, which provided the model for social legislation that later became the New Deal. Or we marvel at the courage of Harry Hay, who decades before Stonewall (much less, recent advances for gay marriage) founded the first American homosexual rights organization. Or we learn that rather than benevolent white officials, African-Americans were the primary driving force behind the civil rights movement, and yet some Southern whites risked condemnation and even death to combat racism: Virginia Durr was one such person.

As Dreier suggests, the greatest Americans might well be viewed as heroes, but they were not saints. Some had less than exemplary personal lives, to the detriment perhaps of friends, spouses and children. Others sometimes took stances that seemingly contradicted their otherwise progressive records: a surprisingly racist episode, an unexpected endorsement of eugenics, an apology for government repression and so forth.

More egregious, perhaps, were those whose records included significant failures, but who made it into Dreier’s Hall of Fame, nevertheless. To the extent that these cases are defensible, it seems a matter of whether the good sufficiently outweighs the bad. For example, can Theodore Roosevelt’s efforts for conservation and against monopolies offset his imperialistic and aggressive foreign policies? Or, can Earl Warren’s “due process revolution” compensate for his leading role in the World War II Japanese-American evacuations? Or, can Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society” prevail over his unconscionable escalation of the Vietnam War? The reader will have to decide. But while we might lament some of their shortcomings, these Americans come across as complex individuals, as fully human, with accolades and flaws, accomplishments and mistakes.

Rather than end the discussion, Dreier’s book provokes it, and this is one of its great values. We’re compelled not merely to learn about the individuals Dreier includes but to devise our own “Hall of Fame” criteria. We’re prompted not only to admire Dreier’s choices but also to second-guess them. And, in turn, to come up with our own “greatest” Americans.

Dreier indicates his own misgivings about having to narrow his own list down to 100 people, and thus he provides another 50 great Americans who arguably he could have included. On that list, it’s painful to see Margaret Mead, Benjamin Spock, John Steinbeck, Allen Ginsberg and James Baldwin among those mentioned. Who else should have been a candidate? My list of nominees would have included Oliver Stone, Jane Fonda, John Reed, Mother Jones, Isadora Duncan and Curt Flood or Marvin Miller. Who would have been on your list?

Many of Dreier’s “greatest” had their impact primarily on American society and history. It’s worth mentioning, however, those in the book whose impact went beyond US borders and addressed larger, global concerns. For example, Eugene Debs opposed US involvement in World War I, and made some of the most memorable observations in opposition to all wars and to their typically imperialistic impulses. A.J. Muste and Albert Einstein made memorable contributions to nonviolence and to the quest for nuclear disarmament. Eleanor Roosevelt was a pioneer in establishing international human rights law. Paul Robeson used his incomparable language, acting and musical talents to become an important crusader against cultural imperialism. Malcolm X stretched himself beyond the US to make some of the first connections of solidarity between Africans and African-Americans. Noam Chomsky and Howard Zinn have been the voice of America’s conscience on US foreign and military policies from Vietnam to current times. While much work remains, these Americans have helped make not merely a more progressive nation but a more just and peaceful world.

While the introduction and biographical essays alone would have made this into a fine book, Dreier’s conclusion, “The 21st Century So Far,” adds an important and valuable piece. It’s a comprehensive survey of the last decade’s political actions and movements. And yes, it identifies many Americans who might be candidates for a follow-up volume, 90 years from now: “The 100 Greatest Americans of the 21st Century.” Dreier also uses the conclusion to help make sense of the 20th century’s movements and leaders. That is, progress is an unending struggle. The work of 20th century agitators provides the foundation for political action in this century. Social advancement is never complete, and will sometimes suffer not merely losses but also retreats. Even so, we can and should be bolstered by an appreciation of what has already been accomplished. The “heroes” of America’s last hundred years can inspire us to be the heroes of the next century.

Peter Dreier’s The 100 Greatest Americans of the 20th Century: A Social Justice Hall of Fame should be required reading, and perhaps it will inspire a similar book that identifies the most progressive and accomplished individuals, from all nations and peoples, who have helped make a better world.

See also:

“A Totally Moral Man”: The Life of Nonviolent Organizer Rev. James Lawson

Eleanor – The Radical Roosevelt Deserves Her Own Worthy Film

Henry Wallace, America’s Forgotten Visionary

Betty Friedan’s “The Feminine Mystique”: 50 Years Later

Radical Reading: The Progressive Dr. Seuss

C. Wright Mills Would Have Loved Occupy Wall Street

The Invisible Poverty of “The Other America” of the 1960s Is Far More Visible Today