The above quote greets readers on the home page of a new Zinn Education Project report on state education standards on Reconstruction — and how this crucial history is taught, and mistaught, across the country.

Reconstruction refers to the period following the Civil War until around 1877 when a radical movement for Black power and wealth redistribution swept the country. The consequences of Reconstruction’s unfinished revolution surround us, permeate our experience of daily life, provide crucial lessons for understanding our world today and suggest important methods for uprooting systemic racism. And for that very reason, guardians of the status quo have long sought to hide Reconstruction’s unprecedented advancements for Black people from students in a concerted effort to deny them the anti-racist lessons this history affords.

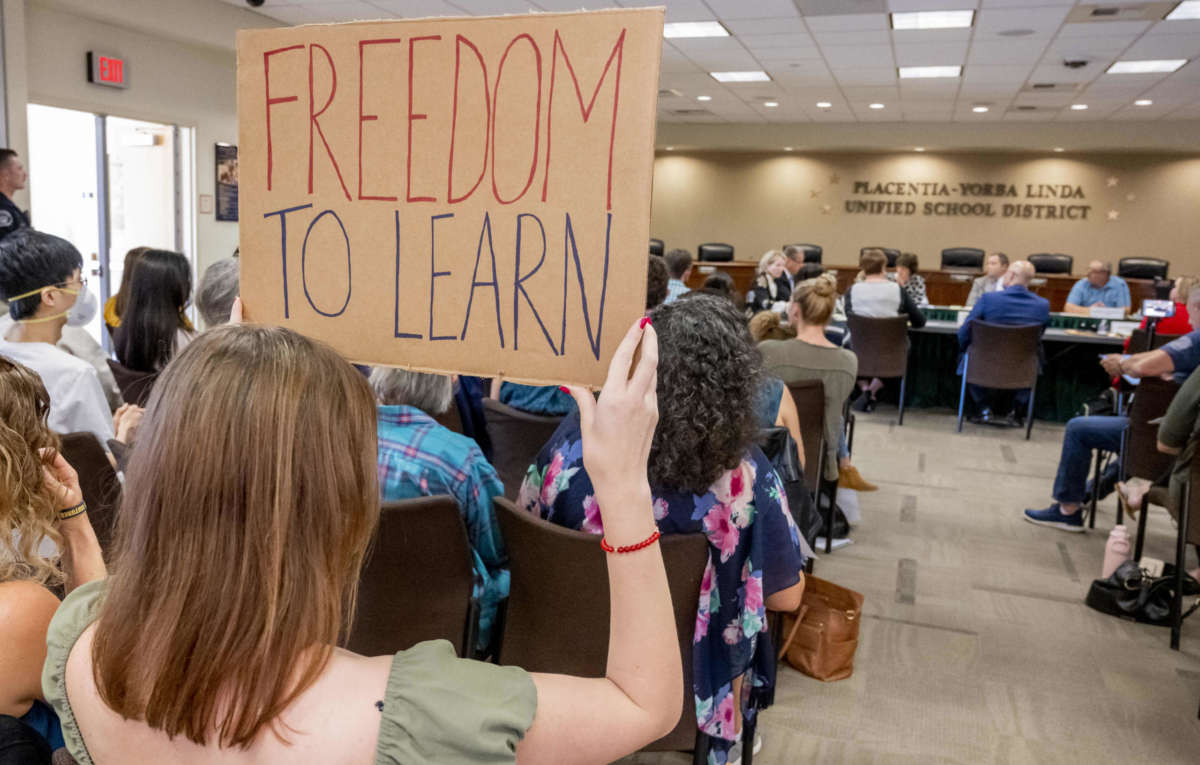

With the current assault on education, the attack on truthful teaching about Reconstruction has dramatically intensified. Some 41 states have introduced legislation or pursued other measures that inhibit conversations about race and seek to mandate that educators conceal the history of structural racism in the U.S. Fifteen states have actually imposed these restrictions.

“Systematic racism should not be taught to our children,” State Sen. Michael McLendon argued during the Mississippi legislature debate on the anti-critical race theory bill, which he introduced. Quite evidently, he doesn’t mind perpetuating systemic racism by sponsoring racist bills, he just has a problem with students learning about it. Upon signing this bill into law, Gov. Tate Reeves claimed that teaching about systemic racism serves only to “humiliate” students. Historian Stephen West pointed out the irony and familiarity of this language, which was used during Reconstruction by congressional Klan supporters “causelessly humiliated” by strides toward racial justice.

From Alabama to Arizona, from Missouri to North Carolina, educators around the country have told the Zinn Education Project they fear these laws will further restrict Reconstruction education, which was already woefully neglected and distorted. Lee R. White is a high school social studies teacher in Winthrop, Iowa, one of the states that ban teaching about racism, sexism, and other so-called “divisive concepts.” White says that “the political climate of the conservatives pushing back against teaching anything negative about our history” threatens to seriously interfere with the teaching of Reconstruction. Denny McCabe, a retired Iowa educator, noted that these efforts could create a “chilling effect on current teachers who need to teach about white supremacy and racism in order to do justice to the topic.”

Our report, “Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle: How State Standards Fail to Teach the Truth About Reconstruction” — the first comprehensive study of all state standards on Reconstruction — found that states’ established education standards overwhelmingly ignore the role of white supremacy in ending Reconstruction, reproduce a racist and false framing of Reconstruction, and obscure the contributions of Black people to Reconstruction’s achievements. Only Massachusetts’ standards mention white supremacy and its direct link to the rise of the Ku Klux Klan, the passage of Black Codes and Jim Crow laws, and the defeat of Reconstruction. Georgia’s “Standards of Excellence” instruct teachers to “Compare and contrast the goals and outcomes of the Freedmen’s Bureau and the Ku Klux Klan [KKK].” (The Freedmen’s Bureau was a government agency founded to help provide freed people with the shelter, clothing, supplies and education they needed after the civil war; the KKK is a terrorist organization. Asking students to compare the two creates a dangerous false moral equivalence.) Zinn Education Project curriculum writer Ursula Wolfe-Rocca describes some of the other problems with state Reconstruction standards:

In many states, Reconstruction only appears on a list of topics or themes teachers should address for a particular time span; in Maine, Reconstruction doesn’t even merit that much space. Maine’s standards define the period 1844–1877 as “Regional tensions and the Civil War.” Connecticut too leaves out Reconstruction in its list of themes like Westward Expansion, Industrialization, and the Rise of Organized Labor.

Why are the lessons of Reconstruction under attack or hidden from students? Because the right-wing attack on voting rights, the attack on critical race theory and the escalation of open white supremacy are all aided by what Professor Henry A. Giroux calls the “violence of organized forgetting.” Giroux describes the violence of organized forgetting as an effort by elites to hide vital lessons of the past that could empower social movements such as “the historical legacies of resistance to racism, militarism, privatization and panoptical surveillance [which] have long been forgotten and made invisible in the current assumption that Americans now live in a democratic, post-racial society.”

Given the severity of this intellectual violence, we must defend ourselves with what I will call the “healing of organized remembering” — collective efforts, in schools, but also in social movements, to recover vital historical lessons about challenges to injustice that have been concealed. Retrieving the legacy of Reconstruction is one of the most important undertakings towards this healing.

Reconstruction was an era of mass social movements and unprecedented advancement for racial justice. With the system of slavery just recently abolished, more than 1,500 Black Americans were elected to office, many in majority-Black districts whose people could vote for the first time. In the 1860s and 1870s, 16 Black Americans served in Congress, about half of whom were formerly enslaved. The 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments — known as the Reconstruction Amendments — were added to the Constitution, and, respectively, abolished slavery (with the shameful exception to those who are imprisoned for a crime), extended citizenship rights to Black people and granted Black men the right to vote. The exhilarating foment during this original era of Black Power are captured by the report’s description of Reconstruction:

Black people organized to fulfill freedom’s promise. They struggled to set the terms of their own labor, advocated for state-funded public education, access to land, the right to vote, and the right to serve on juries. They participated in state constitutional and political conventions, built churches and mutual aid organizations, and ran for and held political office at every possible level of government.

Yet the forces of white supremacy led a brutal counterrevolution that ultimately defeated Reconstruction. One of the primary strategies to dismantle Reconstruction was the war on Black education — just as today’s GOP attack on what it calls critical race theory is a centerpiece of its strategy for reelection and reversing the gains of the uprising for Black lives. Black people understood that there was no true emancipation without education, and after the Civil War, they set about building the first public school system in the South. Consequently, white supremacists were threatened by the hundreds of schools built by Black people. Historian Adam Fairclough explains, “The root of the issue was the same as ever: white control over Black labor. Planters and landlords worried that education diminished their supply of cheap labor by drawing Blacks from the country to the city, away from tenancy, sharecropping, and day labor.” Fairclough quotes one white resident of North Carolina saying, “To give him any education at all takes him out of the field and he is not worth anything to the farmer.” This sentiment was behind the Klan and other terrorists burning down well over 600 Black schools between 1864 and 1876.

The attack on truthful education today must be understood in this historical context. Black education and anti-racist instruction have always posed a threat to an American social order built on a foundation of structural racism. The irony is the attack on critical race theory in education confirms one of the central claims of the theory: that any advancements for racial justice will be met with a white supremacist backlash. This was the case when Black people started the Reconstruction revolution, and it’s the case today in the wake of the 2020 uprising for Black lives, described by The Washington Post as the broadest protest in U.S. history.

A concerted effort has been made throughout history to distort, sequester and deny the strides toward a multiracial democracy that Black people made during this incredible period. And yet, racial justice organizers, Black scholars and social movements have always kept alive the true legacy of Reconstruction. In his 1935 masterpiece, Black Reconstruction, W.E.B. Du Bois debunked the white supremacist “Lost Cause” narrative that advanced the pseudohistory of a noble Confederacy defending itself from northern aggression. Black leaders often referred to the civil rights movement as the Second Reconstruction and Martin Luther King Jr. very much understood the importance of the first one, saying,

White historians had for a century crudely distorted the Negro’s role in the Reconstruction years. It was a conscious and deliberate manipulation of history and the stakes were high. The Reconstruction [era] was a period in which Black men had a small measure of freedom of action … far from being the tragic era white historians described, it was the only period in which democracy existed in the South.”

Today, educators, students and parents are building a movement to teach truthfully about structural racism and raising their voices against the violence perpetrated on students’ intellectual development when Reconstruction is erased in school. Over 8,000 educators have signed the Zinn Education Project’s pledge to teach the truth about structural racism and oppression. In an open letter aimed at school administrations around the country, over 200 scholars of U.S. history urge “school districts to devote more time and resources to the teaching of the Reconstruction era in upper elementary, middle, and high school U.S. history and civics courses.”

The task that remains for those of us interested in making Black lives matter to the institutions and political structures of our society is to complete — and extend — the efforts that were undertaken during Reconstruction. As Ann Arbor middle school teacher Rachel Toon said, “Reconstruction is the single most important era for students to understand. Everything that is happening in their world today can be traced back to the way Reconstruction happened — and how it was thwarted.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $27,000 in the next 24 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.