Farmers and environmental activists are trying to fight a proposed pipeline that would bring Bakken crude through Iowa. But with little information from the company or the government, they’re left in the dark – and are struggling to organize across ideological divides.

Apparently – supposedly – it caught everyone by surprise. Without any previous announcement or public consultation, Iowa media reported in July that a Texas company, Energy Transfer Partners (ETP) plans to build a $5 billion, 1,100-mile pipeline to go through 17 Iowa counties.

It would bring at least 320,000 barrels of crude per day from the Bakken oil fields in North Dakota through South Dakota and Iowa and to refineries in Illinois before it’s finally shipped to the Gulf Coast, primarily for export.

The state’s governor, uber-conservative Terry Branstad, said he hadn’t heard of the proposed project before the news broke. (The office of his gubernatorial opponent, Jack Hatch, tells Truthout that Branstad had met with ETP before the pipeline was publicly announced. Upon seeking comment, Branstad’s office flatly denied this). The governor is supportive of the Keystone XL, but hasn’t yet made up his mind on the Iowa project. Hatch himself has noted that Bakken oil is “notoriously volatile,” but hasn’t come out with a specific stance on the project, saying he needs more information before doing so.

Senate candidates Democrat Bruce Braley and Republican Joni Ernst also haven’t directly said yay or nay, although Braley waxes on about energy independence and the pipeline’s potential impact to the local environment, while Ernst, a strong proponent of the Keystone XL, says she was “eager to learn” about the project.

Most of Iowa’s landowners were just as in the dark as their politicians claimed to be when the news broke. For many, the first they heard of the project was when ETP asked to survey their land. Concerned about the impact of the pipeline on Iowa’s already over-stretched water sources, crop yields and the threat of oil spills, many are saying no to the requests.

Arlene Bates is a landowner in Ankeny, Iowa who’s against the pipeline because she’s “concerned about the contamination risk both to the water and the aqueducts in the area, plus also to the valuable farm ground being contaminated by the volatile fluids they would be pumping through the pipeline,” Bates told Truthout. She’s written letters to her local engineer and board of supervisors, as well as to the governor and Iowa Utility Board, or IUB, the state agency charged with making the final decision on the project, and is also putting together a legal petition officially voicing her opposition.

Bates and other landowners are supported by some local politicians and a handful of environmental and community groups that organized community meetings and rallies over the summer and most recently delivered a petition with 2,300 signatures to Governor Branstad, asking him to reject the project. Critics point out that there have been 100 pipeline spills in the state, home to over 50 pipeline operators, since 2004, accounting for $20 million in property damage.

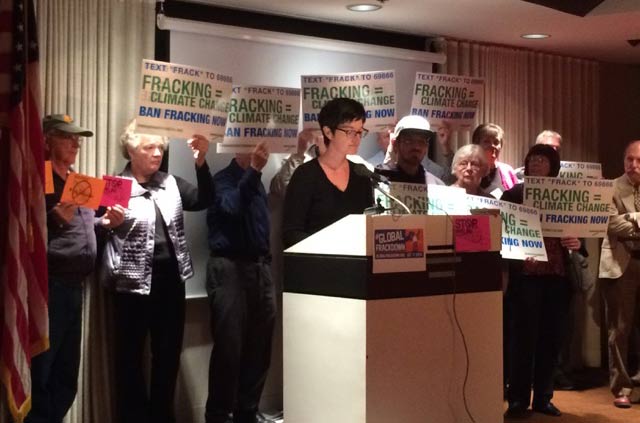

Wally Taylor, Iowa Sierra Club, at Global Frack Down, October 14 2014, Branstad’s office, Des Moines. (Photo: Matt Ohloff, Food and Water Watch)

Wally Taylor, Iowa Sierra Club, at Global Frack Down, October 14 2014, Branstad’s office, Des Moines. (Photo: Matt Ohloff, Food and Water Watch)

In the Dark

But those against the pipeline have little information to go on, stymieing organizing efforts. Save for what’s been reported in the media, they don’t know where the pipeline would go – all that has been offered by ETP is an unspecific map – or which landowners have been contacted for surveying. Despite similar meetings already having been held in other states that would form part of the Dakota Access Pipeline, informational meetings on the Iowa leg of the project will be held in December only – after which ETP can officially file an application for the project with the IUB. Once an application is filed, ETP no longer has to ask permission to survey land.

Jimmy Centers, communications director for Governor Branstad, promises “the public is going to have an abundance of opportunity to voice their opinion on the pipeline” with the upcoming December meetings and another final public hearing before the IUB makes its final decision.

But many are saying this isn’t enough. “Over and over again people say that they’re waiting . . . for those hearings, but the information will likely only come from the company, so these meetings won’t be very helpful,” Angie Carter told Truthout. Carter is a PhD candidate studying Sociology and Sustainable Agriculture at Iowa State University in Ames, Iowa and a board member of the Woman, Food and Agriculture Network (WFAN), a nationwide organization based in the Midwest.

Carter is pushing the government to conduct an independent social and environmental impact assessment of the project to offer more comprehensive information, and says the lack of information offered thus far is deliberate.

“The ‘wait and see’ sentiment is something that the company and those who are in support of this pipeline are putting out there to try to quell dissent,” she says. “It’s negligence that we haven’t seen more leadership from public officials, who just say they’re waiting.”

Community and environmental organizations central to the anti-pipeline fight, such as Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement and Food and Water Watch, note that Governor Branstad’s administration has a history of secrecy, sometimes making decisions behind closed doors. Wally Taylor, legal chair of the Iowa chapter of the Sierra Club, is also worried that the utility board will follow Branstad’s conservative approach, given that all of its members were appointed by the governor.

Petition against pipeline given to Branstad’s office October 14 2014. (Photo: Joseph Lekowski)

Petition against pipeline given to Branstad’s office October 14 2014. (Photo: Joseph Lekowski)

Fighting Back Anyway

But even without information, Bates and others are still doing what they can. “We’re trying to make contact with other people who have received letters [from ETP],” she told Truthout, but without these names being publicly disclosed and with scant information on where the pipeline is proposed to go, Bates says it’s hard to know where to start.

“Right now we’re just relying on word of mouth,” she says. “Farmers will talk at the grain elevators, and we’ll start to learn about other people that way.” Given that farmers are busy with this year’s harvest, there’s little time for organizing.

Limited information is also stalling comprehensive organizing efforts to connect environmental activists with landowners. Adam Mason, State Policy Organizing Director for CCI, told Truthout the organization is trying to reach out to landowners to “build a base, so that when the time comes and we have to mobilize, we have the numbers.” But many environmental organizations are primarily concentrated in cities and haven’t been able to contact potentially impacted landowners because ETP has not disclosed who they have contacted. Therefore, activists are primarily waiting for the December meetings to do so.

Substance, not just process, may also throw a spanner in the works of broad-spectrum organizing. While many farm owners may be concerned about the potential impacts on their own land, they may not want to join a group concerned with bigger environmental issues.

For example, the Iowa Farm Bureau, the largest farmers’ organization in the state, is widely considered to be conservative and pro-big business. It has endorsed Branstad and Ernst in the upcoming election and has questioned anthropogenic climate change (as of last year, only 16 percent of Iowa’s farmers surveyed believed that climate change is occurring and is human-made).

The bureau’s president, Craig Hall, has said he understands farmers’ concerns about the pipeline, but also sees the need for greater supply of domestic oil and notes a pipeline may be a better option than rail, as trains are increasingly overwhelmed with oil, delaying grain shipments from the Midwest. Without taking a public stance on the project, the Farm Bureau is encouraging its members to contact lawyers so they know their rights when they’re approached by ETP.

Other landowners’ organizations voice similar arguments. Jana Linderman, president of the Iowa Farmers’ Union, told Truthout that the pipeline, while far from ideal, would provide short-term relief from overcrowded rail tracks carrying Bakken oil, which pose the threat of crashes and spills. But the union, bureau and most farm and landowners’ organizations simply say they need more information before being able to take sides. They’re primarily consulting with members behind closed doors.

Given farm organizations’ middle-of-the-road stance, WFAN’s Carter says landowners’ involvement shouldn’t be contingent upon building a progressive campaign. “I think it would really be short-sighted if people focused only on the farmers and only focused on Iowa,” she told Truthout, noting that learning about what is happening in North Dakota has spurred her activism against the Iowa pipeline.

“Those boom towns are just horribly destructive [in the Bakken oil field]. They raise cost of living; they’re lawless towns – and violence against indigenous people and indigenous women has been extreme. We’re seeing the ecological destruction and exploitation of people, especially women.

“This pipeline is bad for Iowa; it’s bad for those who live in the North Dakota oil field region; it’s bad for our climate,” says Carter.

Carter says that building an anti-pipeline movement that hinges on environmental movements isn’t so far-fetched an idea. “Most farmers will say they don’t believe in climate change,” she says. “But most people in Iowa do believe in climate change: they live in urban areas, and we need to talk to those people as well.”

Iowa is a state proud of its push for renewable energy. Nearly 28 percent of its electricity comes from wind, compared to just under 5 percent nationally. Iowa’s drivers’ license even sports a picture of wind turbines. NextGen Climate Action, billionaire Tom Steyer’s super PAC, which aims to put climate change at the forefront of politics, has focused on Iowa’s upcoming Senate race, funding ads attacking Ernst and supporting Braley.

Activists storm Branstad’s office Global Frackdown October 14 2014. (Photo: Matt Ohloff, Food and Water Watch)

Activists storm Branstad’s office Global Frackdown October 14 2014. (Photo: Matt Ohloff, Food and Water Watch)

Room for Compromise

Carter hopes that women, who, she notes, own or co-own approximately half of all of Iowa’s land, might help to bridge the environmental and landowning contingents of the anti-pipeline movement.

“Women are more likely to care about community health and public health, and the legacy and sustainability of their land,” she says. “While a lot of landowners are talking about what it means for land, women are saying we don’t want this in Iowa, and we don’t want this anywhere.”

Food and Water Watch Iowa organizer Matt Ohloff told Truthout that learning from other cross-sectional movements can inform efforts broad-based in Iowa. “[The fight against the pipeline] has the potential to cross politics and politician boundaries for a number of issues, whether it’s environmental concerns or property rights, which played out in Nebraska and could play out here,” he says.

Local activists are trying to learn from the fight against Keystone XL, with Iowa representatives from the nationwide Climate March Skyping in organizers from the anti-KXL group Bold Nebraska at public meetings this summer. Iowa organizers have also reached out to groups in Minnesota and Appalachia.

The threat of eminent domain may also be key to radicalizing otherwise apathetic communities and spurring a collective fight. Eminent domain is a legal mechanism that allows the state to require that private land be used in a project deemed to be in the public interest. In the case of the pipeline, it could be used if the IUB gives the project the thumbs up, with landowners who don’t enter a voluntary agreement with the company being forced to allow the company to use their land in exchange for compensation. Carter notes that small-scale farmers, like those running CSAs or a small fruit and vegetable farm, would be most sorely impacted by eminent domain.

Support of eminent domain is a political third rail for public figures of all stripes in Iowa. Individuals, organizations and politicians who are otherwise mum on the project have been outspoken against its use, noting that even if the pipeline goes ahead, ETP should voluntarily obtain consent. Ohloff says a key organizing effort will be to demonstrate to the IUB that the pipeline is “not necessary for the state of Iowa,” given the requirement that any project given eminent domain be considered in the public interest.

This healthy mix of Iowans’ pride over their state’s renewable energy push, focus on individual land rights and protection of farmland, and fledgling environmental movement provoked former state legislator Ed Fallon to tell the Des Moines Register, “a sleeping dragon will be awakened to build a coalition to prevent [the pipeline] from happening.”

The Sierra Club’s Taylor told Truthout. “This pipeline has garnered more opposition and more concern than other environmental issues. Even the fact that the governor has been noncommittal on this project tells me that this is not a project that has a lot of support. I think it’s really just about organizing for now, I think people are against it.”

For her part, landowner Bates is ready for a fight.

“I don’t care about how much money [ETP] offers me, I just do not want them to go through our land,” she says. “We’ve already had to deal with an interstate, a highway, and two electrical lines. We’ve had damage, and we don’t want anything more.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.