The New Orleans skyline is fading in the distance as we fly over the Mississippi River in a small, four-seat airplane on a sunny spring day in early March. It’s been nearly four years since oil from BP’s massive Deepwater Horizon disaster began gushing into the Gulf of Mexico and seeping into the vast system of wetlands and waterways below us. Cleanup and restoration efforts are still ongoing, but the oily legacy of the BP spill is not the only challenge facing southern Louisiana. Two oil refineries pass below us before we see the giant black piles of coal and petroleum coke along the river. Coastal protection organizer Jonathan Henderson asks the pilot to circle the coal terminal, where conveyer belts haul coal through the open air towards barges waiting on the river. Henderson sticks his camera out the window to photograph the black wisps of coal dust swirling in the river waters.

“That’s why we’re suing them,” Henderson says. As we fly southwest toward the Gulf of Mexico, Henderson’s colleagues at the Gulf Restoration Network, along with the Sierra Club and other groups, are busy filing a lawsuit alleging that United Bulk, which operates the coal terminal, has allowed hazardous coal and petroleum coke runoff to contaminate the Mississippi River every day since it began operating five years ago. The company claims it has spent $40 million of a planned $80 million upgrading environmental protections at the facility since state regulators slapped the firm with a compliance order last year, but every photo that Henderson takes tells a different story. He first noticed the coal leaking in 2012, and has photographed contamination in the river ever since. Each shot helps build a case against United Bulk.

The New Orleans customs district, where the United Bulk terminal operates near another terminal and the site of a proposed terminal, ranks second in the nation for coal exports. Residents living near the United Bulk terminal in Plaquemines Parish, just south of New Orleans, complain that wind and rain drive coal and petroleum coke dust laced with toxic heavy metals into neighboring wetlands.

We continue flying over the bayous and wetlands melting into the Gulf of Mexico. The landscape would have looked much different just a few decades ago. Slivers of green marsh protrude like tiny islands from the encroaching waters where the roots of wetland plants once held sediment in place to create a lush ecosystem. Louisiana has lost an estimated 2,000 square miles of coastal land since the 1930s due to expanding levee systems, oil and gas development and rising sea levels. Several communities, including Native American communities that have harvested seafood in the area for generations, are facing relocation due to coastal land erosion.

Stretching into the distance are the vast systems of canals, islands and wetlands that are the subject of a lawsuit filed by the Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority – East against the nearly 100 oil and gas companies producing in the area. The suit alleges the companies owe billions in damages for dredging canals that contributed to coastal land loss, wiping out natural hurricane buffer zones. The lawsuit is now at the center of its own political hurricane as Louisiana’s Republican Gov. Bobby Jindal continues his attempts to politically squash the litigation while environmentalists and Democratic lawmakers rally in support.

Hunting for Oil Spills

Oil leaks from tanks in the southern Louisiana coastal area. Photo: Jonathan Henderson / Gulf Restoration Network and SouthWings.

Oil leaks from tanks in the southern Louisiana coastal area. Photo: Jonathan Henderson / Gulf Restoration Network and SouthWings.

Coal shipping, oil refining, constant coastal erosion – there’s plenty to keep environmentalists like Henderson busy in southern Louisiana. The state is one of the most heavily polluted in the country, and more than 143 million pounds of toxic materials were released by Louisiana’s heavy industries in 2012 alone. But today Henderson’s main target is oil. From the air, he scans the waters below for that familiar rainbow sheen that would indicate a polluting oil platform or a leaky well. Clusters of oil and gas wells, some in operation and others permanently plugged, stand between grids of white PVC pipes that mark areas leased by oyster harvesters.

More than 220,000 oil and gas wells have been drilled in Louisiana over the past century, and more than 64,000 are currently active. Others have been removed, capped or abandoned by operators. Abandoned, or “orphaned” wells, can deteriorate over time due to neglect and leak oil, gas and saltwater into the surrounding area, according to the Louisiana Department of Conservation’s task force, which is charged with cleaning them up.

Oil and gas pipelines crisscross between wells, offshore platforms and onshore refining facilities along the Gulf. An interactive map by the oil and gas watchdog website FracTracker.org displays a thick cluster of purple and yellow dots that mark recent pipeline spills, leaks and accidents stretching along the Gulf region from southern Texas and across Louisiana and Mississippi.

Louisiana Oil Spill Coordinator’s Office estimates that one out of every five gallons of oil that spills in the United States spills in Louisiana. The coordinator’s office says it receives about 1,500 oil spill reports annually. But leaks and spills are a bit like trees falling in the forest. If no one is there to see them – or if oil producers fail to voluntarily report them as required by federal law – then they may never be reported at all.

Henderson’s job is unique; there is no government office that regularly monitors the Gulf and its coastal areas for oil spills. Henderson says that he can’t guarantee that he’ll find an oil leak or spill every time he goes on a flight, but he typically does. “It’s kind of like hunting,” Henderson shouts over the roar of the plane’s engine.

BP and Big Oil’s Dirty Legacy

Coal dust is spotted in the Mississippi River at the United Bulk terminal south of New Orleans. Photo: Jonathan Henderson / Gulf Restoration Network and SouthWings.

Coal dust is spotted in the Mississippi River at the United Bulk terminal south of New Orleans. Photo: Jonathan Henderson / Gulf Restoration Network and SouthWings.

Henderson began his oil hunts during the Deepwater Horizon disaster in April 2010, when BP’s now infamous oil platform and Macondo well suffered a fatal blowout that killed 11 workers and spilled up to 4.3 million barrels of oil into the Gulf of Mexico. The spill remains the largest in US history.

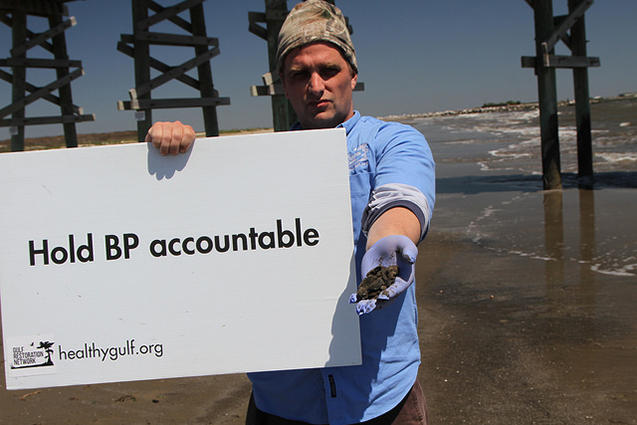

Four years after the spill, Henderson and other independent observers still find tar balls washed up on Louisiana’s southern beaches. When large storms whip up and strip off layers of beach sand, huge mats of fresh oil can be found.

More than 200 miles of Louisiana shoreline continues to display some degree of oiling, according to a February 2014 report by Louisiana’s Coastal Protection and Restoration authority. Nearly 15.2 million pounds of oily material has been removed from Louisiana since state responders began collecting data in June 2011, more than a year after the spill.

Scientists are still uncovering the extent of the ecological damage caused by the Deepwater Horizon disaster. A recent study found that tuna embryos exposed to crude oil from the 2010 spill developed heart problems and other deformities that could eventually kill the fish or at least shorten their lives. Researchers in Florida recently found that 28 to 43 percent of the carbon found in tiny floating particles in the Gulf could be traced back to methane released during the BP spill. Bacteria in the Gulf digested the methane, suggesting that pollution from the spill is now a ubiquitous element of the Gulf’s ecological food chain.

“This whole area back here got filled with oil from BP,” Henderson says as he points out the window of the plane to a bay behind a coastal barrier island. “You’d go through it and have oil three inches thick on the bottom of your boat.”

Shortly after the Deepwater Horizon’s initial blowout on April 20, 2010, Henderson attempted to fly over the growing spill in the Gulf. Henderson and his pilot had to get permission to fly over the spill from the Coast Guard and the Unified Command, a collection of state agencies that teamed up with BP and Transocean to respond to the disaster. BP, Henderson says, “was calling the shots.” Henderson says that someone from the company initially wanted to deny them permission, but his crew “raised hell” and eventually got permission to fly over the spill.

Henderson says he took 20 or 30 flights and “a lot of boat trips” during the BP disaster, tracking the oil as it spread into marshes and bays and monitoring the extensive cleanup effort. Observations made during the trips helped independent experts challenge the lowball estimates of the size of the spill that BP and government officials were releasing to the media.

SkyTruth, a small nonprofit that uses remote sensing and digital mapping to track pollution, was the first independent group to challenge BP’s spill rate estimates. During the initial days of the spill, SkyTruth used satellite imagery of the oil on the surface to estimate that oil was gushing from the Macondo at a rate five to 24 times higher than BP estimated.

As SkyTruth and the Gulf Restoration Network continued to monitor the cleanup efforts in the Gulf, the groups began to notice oil spills and other pollution events that were unrelated to the BP spill. SkyTruth discovered an ongoing leak 12 miles off the tip of the Mississippi River delta where an oil platform operated by Taylor Energy had been damaged by Hurricane Ivan in 2004. A pilot flew over the site and saw an oil slick trailing off into the distance, but no platform. Instead, a submersible rig was working to plug 26 undersea wells, which had been presumably leaking since 2004.

Whenever oil, hazardous materials and other pollutants are released into a body of water, the Clean Water Act requires polluters to file a report with The National Response Center (NRC), a federal communications center staffed by the Coast Guard. The NRC receives thousands of pollution reports from across the US every month, many from polluters themselves, who could face federal fines if they fail to report spills.

SkyTruth has identified more than 1,200 NRC reports from 2004 to 2011 that the group believes to be related to leaks at the Taylor Energy site. In many of the reports, estimates of the amount of oil spilled into the Gulf are dwarfed by SkyTruth’s estimates based on satellite image tracking. Fresh off of publically confronting BP on its Macondo estimates, the analysts at SkyTruth were starting to see a disturbing pattern.

Henderson and the Gulf Restoration Network were seeing a pattern as well. “I began very actively finding more leaks and spills and reporting them to the federal government,” Henderson says. Over and over again, the amount of oil and other pollution reported by the industry to the NRC did not seem to match up with independent observations. It was becoming increasingly clear that oil spills and other pollution events in the Gulf region were much more routine than environmentalists – and the general public – could have expected, and the industries responsible were often underestimating their size and impact in an atmosphere of little oversight.

Thousands of Leaks and Spills

Coastal protection organizer Jonathan Henderson frequently finds tar balls on Louisiana beaches. Photo: Gulf Restoration Network.

Coastal protection organizer Jonathan Henderson frequently finds tar balls on Louisiana beaches. Photo: Gulf Restoration Network.

“I got oil! I got oil!” Henderson shouts as he grabs his camera. “Right over there by the tank battery, there’s a rainbow sheen in the canal.”

Below the airplane, the dark waters of a navigation canal cut through a green marsh. The plane begins circling the white oil tanks in the water, which look like little cylindrical buttons from the air. The telltale rainbow sheen surrounds the tanks, indicating that oil is leaking into the waters. Henderson sticks his camera out the airplane window and begins snapping pictures.

The leak is not anywhere near the size of spills that make headlines, such as the 170,000-gallon crude oil spill in Galveston Bay south of Houston in late March, or the large spill upriver from New Orleans that temporarily halted boat traffic on 65 miles of the Mississippi River in late February. While a small leak is not such a big deal, Henderson says they are all part of a much larger problem.

“It’s a big deal that there are thousands of [leaks and spills] a year, and nobody is getting fined for it,” Henderson says.

In 2013, about 1,900 reports involving some kind of oil released into Louisiana waterways came into the NRC, according to a Truthout review of federal data. About 1,040 releases involved crude oil, and 738 crude oil spills were located in Gulf of Mexico waters.

The polluters themselves filed many of these reports, and that’s a problem, according to Henderson. “There has been this absurd honor system whereby the responsible party, it’s up to them to report a leak or a release of toxic substances, it’s on them to report it and the amount that is reported,” Henderson says. The Coast Guard only responds to spills of a certain size, he says, and oil companies are not always interested in attracting attention.

In a one-year period stretching from October 2010 to September 2011, a total of 2,903 oil release reports were filed with the NRC from the Gulf region, but 77 percent of those reports did not include an estimate of the amount of oil spilled, according to a 2012 report by the Gulf Monitoring Consortium, a coalition formed by the Gulf Restoration Network, SkyTruth and other groups in the wake of the BP spill.

The NRC reports that did include a spill estimate account for a combined 250,000 gallons of crude released into the Gulf during the one-year period.

Using SkyTruth and other analysis tools, however, the consortium estimates the actual total amount spilled during the tie period to be between 1.5 million and 2.2 million gallons.

These massive reporting gaps make it impossible to determine how much oil pollution is actually released in the Gulf of Mexico, let alone Louisiana’s sensitive coastal areas. The Louisiana Department of Natural Resources, which regulates oil and gas drilling, has an average of 12 inspectors who check wells in coastal areas for compliance, but the area is so large that the department’s goal is to inspect one facility every three years.

NRC data indicates the oil leaks and spills are routine in Louisiana, but its unclear if oil and gas well operators are being held accountable. Truthout formally requested data from DNR on the number inspections performed on oil and gas production facilities in 2013 as well as the number of violations and fines issued to operators during that same time period, but DNR officials said an internal records review did not uncover any records matching Truthout’s request. The DNR indicated that there “may” be relevant files in a database of 113 enforcement records related to “coastal use permits.” Truthout reviewed the records and found that some do cite violations of permits held by oil and gas operators, as well as orders to bring operations into compliance with permits, but many do not include fines.

Spokespeople for the department did not respond to repeated inquiries from Truthout seeking details on its enforcement programs and the number of violations issued by oil and gas regulators.

With the help of the North Carolina-based nonprofit SouthWings, Henderson and his colleagues remain the only independent observers who fly over Louisiana’s coastal lowlands and the Gulf of Mexico looking for pollution and oil spills. On our way back from the airport, Henderson explains that he is heading back to his office to upload his photos and file NRC reports on the leaking coal dust and oil we saw during the flight. The reports will show up in an NRC database and on pollution tracking maps produced by Skytruth and the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, another member of the consortium.

Henderson expects to work late into the evening at his office in New Orleans, uploading photographs, entering data and filing reports. He says that a team of three or four people would so the same amount of work at a large nonprofit. As he works, representatives from the largest oil companies in the world will be preparing to meet the very next day in the nearby Superdome, where the Department of Energy be offering to sell 40 million acres of the Gulf of Mexico for oil and gas development. Henderson doesn’t know it yet, but the Obama administration will successfully sell 1.7 million acres for a cool $872 million in revenues. Henderson and the Gulf Monitoring Consortium have their work cut out for them. “Every report, no matter how small, is helping us make an argument for reform,” Henderson says.

Truthout Is Preparing to Meet Trump’s Agenda With Resistance at Every Turn

Dear Truthout Community,

If you feel rage, despondency, confusion and deep fear today, you are not alone. We’re feeling it too. We are heartsick. Facing down Trump’s fascist agenda, we are desperately worried about the most vulnerable people among us, including our loved ones and everyone in the Truthout community, and our minds are racing a million miles a minute to try to map out all that needs to be done.

We must give ourselves space to grieve and feel our fear, feel our rage, and keep in the forefront of our mind the stark truth that millions of real human lives are on the line. And simultaneously, we’ve got to get to work, take stock of our resources, and prepare to throw ourselves full force into the movement.

Journalism is a linchpin of that movement. Even as we are reeling, we’re summoning up all the energy we can to face down what’s coming, because we know that one of the sharpest weapons against fascism is publishing the truth.

There are many terrifying planks to the Trump agenda, and we plan to devote ourselves to reporting thoroughly on each one and, crucially, covering the movements resisting them. We also recognize that Trump is a dire threat to journalism itself, and that we must take this seriously from the outset.

Last week, the four of us sat down to have some hard but necessary conversations about Truthout under a Trump presidency. How would we defend our publication from an avalanche of far right lawsuits that seek to bankrupt us? How would we keep our reporters safe if they need to cover outbreaks of political violence, or if they are targeted by authorities? How will we urgently produce the practical analysis, tools and movement coverage that you need right now — breaking through our normal routines to meet a terrifying moment in ways that best serve you?

It will be a tough, scary four years to produce social justice-driven journalism. We need to deliver news, strategy, liberatory ideas, tools and movement-sparking solutions with a force that we never have had to before. And at the same time, we desperately need to protect our ability to do so.

We know this is such a painful moment and donations may understandably be the last thing on your mind. But we must ask for your support, which is needed in a new and urgent way.

We promise we will kick into an even higher gear to give you truthful news that cuts against the disinformation and vitriol and hate and violence. We promise to publish analyses that will serve the needs of the movements we all rely on to survive the next four years, and even build for the future. We promise to be responsive, to recognize you as members of our community with a vital stake and voice in this work.

Please dig deep if you can, but a donation of any amount will be a truly meaningful and tangible action in this cataclysmic historical moment.

We’re with you. Let’s do all we can to move forward together.

With love, rage, and solidarity,

Maya, Negin, Saima, and Ziggy