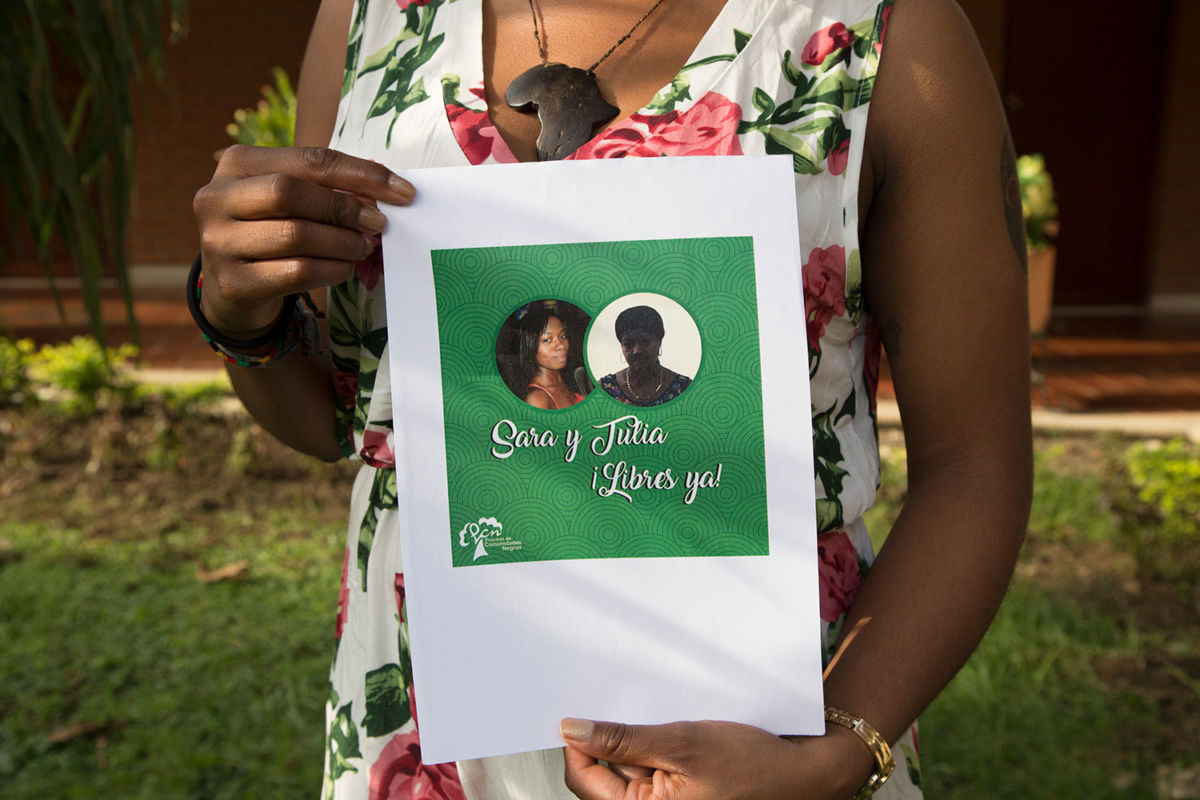

“Sara y Tulia Libres!” (“Free Sara and Tulia!”) declared a colorful butcher-paper sign. It was taped to the floor next to a ceremonial centerpiece composed of flowers, leaves, seeds and other natural elements surrounded by candles that burned throughout the day.

It was late February, and around 30 Afro-Colombian human rights defenders from around the country had gathered in the western Colombian city of Cali for a conference. They were taking stock of their efforts toward meaningful peace and security, and toward racial and gender justice in a country still experiencing violence despite being in a post-peace accord context.

The conference was organized by the Black Communities’ Process (PCN), a national network that has advocated for protections and rights for Afro-descendant Colombians for more than 20 years, and my organization, MADRE, an international women’s rights organization.

At the conference, the human rights defenders strategized how to move forward under the right-wing administration of Iván Duque Márquez, which rose to power last year on promises of undoing key provisions of the government’s 2016 peace deal with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). Afro-descendant regions of Colombia, heavily impacted by conflict, overwhelmingly supported the peace deal. Advocates, including women leaders from those communities, helped secure inclusion of a chapter protecting and promoting Afro-descendant and Indigenous rights, including gender rights.

Given the unceasing threats against and killings of Colombia’s human rights defenders over the last couple years, these activists’ continued advocacy is cause to celebrate. Nevertheless, the fates of Sara Quiñonez and Tulia Maris Valencia weigh heavily in their minds.

Criminalization of Colombia’s Human Rights Defenders

April will mark a year that Quiñonez and her mother Maris Valencia have spent in what amounts to administrative detention in Jamundí, a swamp area about an hour from Cali. The prison in Jamundí, one of the largest in Latin America, was constructed with assistance from the United States Bureau of Prisons. Dedicated members of PCN, both Quiñonez and Maris Valencia are from Tumaco on the southwest coast of Colombia, an area that continues to be heavily impacted by Colombia’s ongoing armed violence.

When arrested, Quiñonez was under protective measures by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and Colombia’s own National Protection Unit. The measures are quite necessary: Quiñonez has faced threats and forced displacement due to her advocacy on behalf of the collective and territorial rights of Afro-descendant peoples and her push for fair implementation of the government’s coca crop substitution program. She was forcibly displaced twice because of her leadership position in the Afro-descendant Community Council of Alto Mira and Frontera. Also a well-known local leader, Maris Valencia was part of the women’s group and local committees of the Community Council. The leadership of the Community Council, one of the recognized units of Black autonomous governance in Colombia, has received repeated death threats. Three of its members have been assassinated since 2015.

Along with about 30 people, the government arrested Quiñonez and Maris Valencia in 2018 on what advocates say are unfounded charges of connections to the guerilla group the National Liberation Army (ELN), as well as narco-trafficking. This tactic is emblematic of the Colombian government’s attempt to smear human rights defenders, particularly from Black and Indigenous communities, as members of armed groups. Both were denied bail, and remain in maximum-security detention awaiting trial. Quiñonez has only been able to see her young daughter once during this time.

The arrests and lengthy administrative imprisonment follow a pattern all too familiar to Afro-Colombians and other human rights defenders, who see this as a state strategy to halt effective human rights work. In March 2017, for example, police arrested Afro-Colombian human rights defender Milena Quiroz, who had denounced environmental destruction by palm oil and mining companies. The Colombian government accused Quiroz of being part of the ELN support network and charged her with conspiracy and rebellion. Four months later, the prosecutor who ordered the arrests was arrested herself for allegedly belonging to a corruption network within the prosecutor’s office that benefited drug traffickers and paramilitaries.

Quiroz, however, remained detained based on this prosecutor’s allegation that she posed a danger if released because the protest marches she helped organize were evidence of a purported connection to the ELN. In November 2017, the prosecutor’s order for preventative detention was revoked due to lack of adequate evidence. In the finding, the judge remarked that the prosecutor’s office was more focused on producing scandalous media headlines than on conducting a useful investigation.

Quiñonez and Maris Valencia’s detention comes as Afro-Colombian women have become more widely recognized as leaders in struggles to protect the environment from destructive mega-projects and illegal mining, to secure their constitutional right to collective territory, to end armed conflict and to confront gender-based violence. Francia Marquez, for example, won the 2018 Goldman Environmental Prize for Central and South America for her years-long work to end illegal gold mining in her community’s territory and to protect the environment. The Canadian Embassy, meanwhile, recently nominated PCN activist Charo Mina-Rojas for its feminist prize for her work on behalf of sexual and gender-based violence survivors, including shepherding a months-long effort to document and report cases of gender-based violence committed against Afro-descendants.

Often framed as a product of armed conflict, targeted killings and other violence against human rights defenders — particularly those whose advocacy impacted the interests of Colombia’s economic and political elites — has long plagued Colombia. While the armed conflict largely ceased following the 2016 peace accord, the killings of such activists continue unabated. More than 550 human rights defenders have been killed since the start of 2016, according to one estimate, and Black and Indigenous communities have been disproportionately impacted. On January 5, 2019, for example, longtime Afro-descendant and displaced victims’ rights advocate Maritza Quiroz Leiva was killed. Her murder came after multiple warnings from Colombia’s public advocate, a government body that promotes human rights adherence and produces early alerts on conflict risks, threats victims’ advocates and social leaders in her region face.

The Search for Meaningful Protections for Human Rights Defenders

In response to international pressure, the Duque government recently announced a “Timely Action Plan” to address the threats and murders of social leaders — a plan representatives of the European Union and other international actors have praised. Colombia’s human rights advocates, however, are concerned that it over-emphasizes military and police responses in communities that are already heavily militarized at the expense of initiatives that address root causes of violence and insecurity. They are also concerned that it fails to provide for implementation of social leader protection programs developed in consultation with impacted communities, as called for by the peace accord. Under the former presidential administration, several communities arrived at agreements with government officials on measures to address the insecurity, but these have yet to be implemented.

Initially appointed to lead the new initiative was Leonardo Alfonso Barrero Gordillo, a retired general who stigmatized social leaders and allegedly obstructed investigations into grave human rights abuses the Colombian military committed. Popular outrage led the interior minister to announce that instead of directing the initiative, Gordillo would serve as a link between the operation of the Timely Action Plan and Colombia’s armed forces and national police — a role that still worries human rights advocates. Notably, the plan comes at a time when the administration has disrupted operation of the body tasked with oversight of peace implementation. The government also is interminably delaying final regulation of a key transitional justice body.

At the February conference, Afro-descendant women leaders — among them women who themselves are under protection due to threats to their lives — raised concerns about gaps in the president’s plan.

“In Colombia, all human rights defenders are considered criminals,” said Danelly Estupiñan Valencia, a feminist activist who faces threats for her advocacy for Afro-descendant communities’ rights in the face of industrial port expansion in the city of Buenaventura.

Local advocates recently called for solidarity with both Estupiñan Valencia and a fellow woman advocate for Buenaventura’s Afro-descendant communities, Leyla Andrea Arroyo Muñoz, after the two noted an uptick in monitoring of their movements and communications. The threats haven’t stopped Estupiñan Valencia from organizing for social justice, nor from calling for meaningful protections for human rights defenders. In order to truly minimize the threat to their lives, Valencia said at the February conference, the Colombian government must take meaningful steps to uphold Afro-descendant and Indigenous ’ territorial rights, including their right to free, prior and informed consent regarding development impacting their communities. Death threats don’t just impact an individual, but “threaten the entire territory,” Estupiñan Valencia explained.

At the very least, advocates hope that the government will re-examine the use of its resources to criminalize threatened Afro-descendant women human rights defenders like Quiñonez and Maris Valencia.

Standing in a circle around the centerpiece and sign, Black women advocates called for Quiñonez’s and Maris Valencia’s freedom — that the prison doors will open for them and Quiñonez’s young daughter will finally be able to hug her mother.

Press freedom is under attack

As Trump cracks down on political speech, independent media is increasingly necessary.

Truthout produces reporting you won’t see in the mainstream: journalism from the frontlines of global conflict, interviews with grassroots movement leaders, high-quality legal analysis and more.

Our work is possible thanks to reader support. Help Truthout catalyze change and social justice — make a tax-deductible monthly or one-time donation today.