Did you know that Truthout is a nonprofit and independently funded by readers like you? If you value what we do, please support our work with a donation.

In 1964, at the height of the civil rights movement, the great organizer Ella Baker said, “Until the killing of black men, black mothers’ sons, becomes as important to the rest of the country as the killing of a white mother’s sons, we who believe in freedom cannot rest.”

Fifty years later, Baker’s words still resonate. The grieving mothers of Sean Bell, Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown – three young unarmed black men who were shot to death – came together in Ferguson, Missouri, last week to remind us that despite many years of racial progress, our criminal justice system remains a bastion of bias and bigotry.

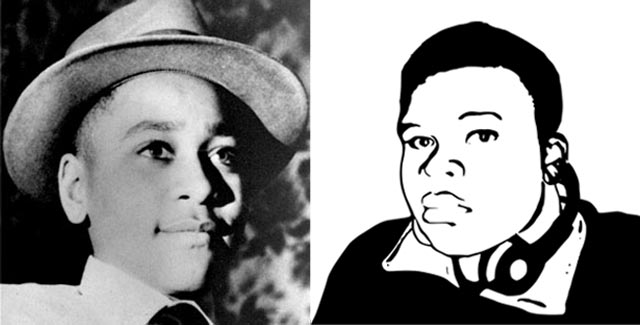

Their grief reverberates with the grief suffered by Mamie Till-Mobley, whose teenage son Emmett Till was murdered by white thugs in Mississippi on August 28, 1955.

Outrage about Till’s murder galvanized the nation and helped catalyze the civil rights movement. It is no accident that three months after Till’s brutalized body was pulled from the Tallahatchie River, African-Americans in Montgomery, Alabama, began their bus boycott.

Rosa Parks, who triggered the boycott movement when she refused to leave her seat on a segregated bus on December 1, 1955, recalled: “I thought about Emmett Till, and I could not go back. My legs and feet were not hurting, that is a stereotype. I paid the same fare as others, and I felt violated.”

In the wake of Michael Brown’s murder – and the many other tragic killings of young black men – even more energy is focusing in support of a movement for economic and racial justice that goes beyond sporadic protests, but instead mobilizes an inter-racial coalition to demand changes in policies and institutions to challenge American racism – from job discrimination to predatory lending to underfunded schools, to the pervasive racism of our criminal justice system.

Michael Brown’s murder by a Ferguson, Missouri, cop has, once again, provoked a national conversation about how far the United States has come in its quest for racial equality. Many people now acknowledge that African-Americans are treated differently than whites by police, judges, juries, prison officials and prospective employers once they are out of prison. Michelle Alexander documents this harsh reality in her recent book, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. Ken Burns reveals it in his recent documentary film, The Central Park Five, which tells the story of the five teenagers from Harlem (four of them black, one of them Latino) who were wrongly convicted of raping a white woman in New York City’s Central Park in 1989 and whose lives were upended by this miscarriage of justice. A recent Urban Institute study reports that when there is a homicide with one shooter and one victim who are strangers, a little less than 3 percent of black-on-white homicides are ruled to be justified. When the races are reversed, the percentage of cases that are ruled to be justified climbs to more than 36 percent in states with Stand Your Ground laws and 29 percent in states without such laws.

Of course, no one had to cite statistics to Mamie Till-Mobley to convince her that there was little justice in our criminal justice system. Emmett, a 14-year-old African-American boy from Chicago, was visiting relatives in Money, Mississippi. The eighth grader allegedly whistled at a white woman in a grocery store after buying some gum, unaware that he’d broken one of the unwritten rules of Jim Crow life in the South regarding relations between blacks and whites. The woman, Carolyn Bryant, was managing the store while her husband Roy was on the road, working as a truck driver. When Roy returned and heard his wife’s version of Till’s behavior, he recruited his half-brother, J.W. Milam, and at 2 am on August 28, they kidnapped the teenager from his great-uncle’s house.

After brutally beating Till, the pair shot him in the head. Three days later, Till’s body was discovered in the Tallahatchie River, with a 75-pound cotton gin fan fastened around his neck with barbed wire. His face was horribly battered; his head was swollen and bashed in, his eyes bulged out of their sockets and his mouth was broken and twisted.

Till’s body was sent back to Chicago. Huge crowds came to hisSeptember 6funeral. His mother insisted that the casket remain open so people could see how her son had been mutilated. In itsSeptember 15issue,Jet magazine published a photo of his face. His killing became a symbol of the many black victims of white “vigilante justice,” including the long history of lynching.

Bryant and Milam were arrested and charged with murder. Neither man could afford a lawyer, but five local attorneys volunteered to represent them for free. At the trial, Moses Wright, Till’s great uncle, bravely stood up on the witness stand and identified the two white men who kidnapped Emmett at his home. It didn’t matter. OnSeptember 23, an all-white, all-male jury took only an hour to acquit both men of Till’s murder, despite their admission that they had kidnapped him.

Shortly after the trial, a white southern reporter, William Bradford Huie, interviewed Bryant and Milam and paid them $4,000 to tell their story, which was published in Look magazine. The two men boasted about killing Till. “As long as I live and can do anything about it, niggers are gonna stay in their place,” Milam said. They killed Till, they explained, to make an example out of him, to warn others “of his kind” not to visit the South.

The black community was helpless to convict Bryant and Milam in court, but they exacted another form of nonviolent retaliation. The Bryant and Milam families operated a chain of small stores in the Mississippi Delta that depended on black customers. After Till was slayed, blacks boycotted these stores and they soon were closed or sold.

Filmmaker Keith Beauchamp was 10 years old, living in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, when he discovered a copy ofJet magazine in his parents’ study and saw a photograph of Till’s face. “It just shocked me,” Beauchamp told The Progressive magazine a few years ago. “Emmett was 14 years old, and it was like a mirror image of myself – this young boy who was murdered for whistling. I’ve always had that vision of Emmett Till’s corpse etched in my head.”

Beauchamp’s remarkable 2005 documentary, The Untold Story of Emmett Louis Till, weaves together archival photos, newsreel footage and interviews to recount the gruesome story of the murder and its aftermath, including some information that the filmmaker uncovered suggesting that more than two people had participated in Till’s killing.

The murder and the trial, and then the confessions in theLook story, horrified the country. For many white Americans, it was shocking. For most black Americans, it confirmed what they already knew. For young African-Americans growing up in the postwar decade it was an awakening. Till’s murder became lodged in the nation’s psychic memory as a font of anger and outrage that galvanized a protest movement that would eventually change the country.

A key milestone was the Montgomery bus boycott, which succeeded in dismantling Montgomery’s bus segregation laws. Equally important, it propelled the civil rights movement into national consciousness. Martin Luther King, then a 26-year-old minister in his first job, became a public figure. The boycott’s success led King and other black ministers to form the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which became a major instigator of civil rights protest. The movement picked up steam after February 1, 1960, when four black college students in Greensboro, North Carolina, organized the first sit-in at a Woolworth’s lunch counter. The sit-in strategy spread quickly throughout the South, led primarily by black college students who formed the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

The boycotts, sit-ins, Freedom Rides, voter registration campaigns, and other protest activities gained momentum. One of the civil rights movement’s major milestones occurred on August 28, 1963 – 51 years ago – when 250,000 people participated in the March on Washington. It was the largest mass protest in US history at that time. It was made possible because there was a powerful grassroots movement engaged in local organizing around the country. It was called a march “for jobs and freedom” in order to link the demand for full employment with the demand for civil rights. It had both a broad vision and a specific set of legislative goals.

A year later, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act. The following year, it passed the Voting Rights Act. In 1967, the Supreme Court, in Loving v. Virginia, ruled that state laws that banned interracial marriage violated the US Constitution. The civil rights movement dismantled the nation’s racial apartheid system in many ways. It was a movement led by African-Americans, but they had many white allies. It was a truly interracial movement. But more remains to be done.

Will the memory of the killing of 18-year-old Michael Brown play a role that is similarly catalytic to that of Emmett Till’s murder and the acquittal of his killers?

Brown’s murder has sparked protests throughout the country. It is a remarkable outpouring of anger and frustration. Powerful sentiments are being expressed; the question is, how do they translate into specific changes that will alter social conditions and laws that exploit and oppress people? As the great abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass once said, “Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.”

The demands that are getting the most attention deal with police abuses. In Ferguson as in many communities, people are demanding more African-American police officers. Many protesters are calling for local police to end racial profiling that leads cops to stop, harass and arrest black men at a much higher rate than they do whites. Many are challenging the hyper-militarization of local police departments – including the use of military-style vehicles and guns.

We are also hearing demands for states to rescind the Stand Your Ground laws that gave George Zimmerman his excuse to kill Trayvon Martin. In 2005, Florida was the first state to enact this law, which permits armed vigilantes to take the law into their own hands. Since then, 25 other states have followed suit. These “shoot first” laws are the result of lobbying efforts by the National Rifle Association and the American Legislative Exchange Council, a right-wing lobby group composed of big corporations and conservative state legislators. The NRA and ALEC are the modern equivalent of lynch mobs.

It was an incident of police abuse that triggered the current protests, but it is the ongoing frustration and anger over racial injustice that will sustain a movement for fundamental change. The original demands of the 1963 March on Washington for “jobs and freedom” – full employment, living wages, voting rights and a dismantling of segregation – remain unfulfilled.

Most obviously, the so-called economic “recovery” has not taken hold in most African-American communities, where unemployment and foreclosures are significantly higher than in other parts of the country.

-

Nearly half of poor black children live in neighborhoods with concentrated poverty; however, only a little more than a tenth of poor white children live in similar neighborhoods.

-

Three quarters (74.1 percent) of black children attend majority non-white schools. These segregated schools do not have the same resources as schools serving white children, violating the core American belief in equality of opportunity.

-

The black unemployment rate (14 percent) is currently 2.2 times higher than the white unemployment rate, a bigger discrepancy than at any point since 2007. This is higher than the average national unemployment rate of 13.1 percent during the Great Depression, from 1929 to 1939. Even among people with comparable levels of education, black unemployment rates are higher.

-

Black median household income ($33,764) is about 60 percent of whites ($56,565), down from 62 percent before the recession. 28.1 percent of blacks live in poverty versus 11 percent of whites.

-

After adjusting for inflation, the minimum wage today – $7.25 – is worth over $2.00 less than in 1968, and is nowhere close to a living wage. African-Americans comprise 14.8 percent of the country’s workforce, but 28.4 percent of the workers who would be affected by increasing the minimum wage to $10.10 an hour. That means 4.1 million African-American workers would get a raise.

-

The wealth gap between whites and blacks almost tripled from 1984 to 2009, increasing from $85,000 to $236,500. The median net worth of white households grew to $265,000 over the 25-year period compared with just $28,500 for the black households. Since then, the disparity has widened further because the value of black-owned homes has declined more than that of white-owned homes and the foreclosure rate of black homeowners, disproportionately victimized by predatory lending, is much higher than that of whites.

-

A report by the Violence Policy Center, found that black males are nine times more likely than white males to be the victims of homicide – 29.50 out of 100,000 black males compared with 3.85 out of 100,000 white males.

The crusade for racial justice is multifaceted and has a broad agenda, including a push for full employment, an increase in the minimum wage above the poverty level, adequate funding for education from kindergarten through college, a restoration of voting rights to challenge efforts by many states to suppress the black vote, and stronger gun control laws to address the epidemic of killings that destroy the lives of people across the racial divide, but that disproportionately victimize African-Americans.As many have noted, it is important to view the turmoil in Ferguson in a larger context. Consider the words of Rev. William Barber, president of the North Carolina NAACP and the inspirational leader of that state’s broad Moral Monday movement, at a rally in Durham, North Carolina.

“It’s about Michael Brown. But, it’s also about all the stuff that happened before Michael Brown,” Barber said. “And it’s about unarmed black men being killed by police, that’s the narrative. Secondly, we’ve got to call together broad allies, this can’t just be black people speaking to this. It’s got to be black, white, Latino, Republicans and Democrats saying, it’s just wrong.”

A terrifying moment. We appeal for your support.

In the last weeks, we have witnessed an authoritarian assault on communities in Minnesota and across the nation.

The need for truthful, grassroots reporting is urgent at this cataclysmic historical moment. Yet, Trump-aligned billionaires and other allies have taken over many legacy media outlets — the culmination of a decades-long campaign to place control of the narrative into the hands of the political right.

We refuse to let Trump’s blatant propaganda machine go unchecked. Untethered to corporate ownership or advertisers, Truthout remains fearless in our reporting and our determination to use journalism as a tool for justice.

But we need your help just to fund our basic expenses. Over 80 percent of Truthout’s funding comes from small individual donations from our community of readers, and over a third of our total budget is supported by recurring monthly donors.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser, and we have a goal to add 231 new monthly donors in the next 48 hours. Whether you can make a small monthly donation or a larger one-time gift, Truthout only works with your support.