I guess I don’t quite see how Argentina’s default, of all examples, can be viewed as a cautionary tale for Greece.

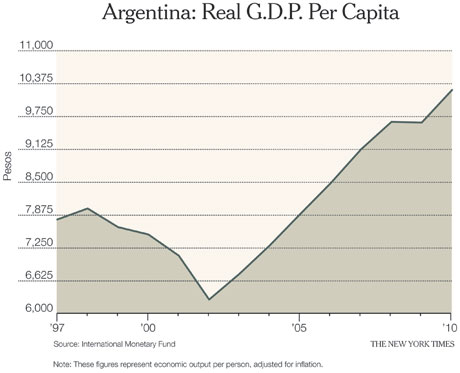

I explained in a previous column that Argentina suffered terribly from 1998 through 2001, as it tried to be orthodox and do the right thing. After it defaulted at the end of 2001, it went through a brief severe downturn, but soon began a rapid recovery that continued for a long time, as the chart on this page shows. Surely the Argentine example suggests that default is a great idea; the case against Greek default must be that this country is different (which, to be fair, is arguable).

I was really struck by a business consultant in a recent article in The Times who said that that Argentina is “no longer considered a serious country;” shouldn’t that be a Serious Country? And in Argentina, as elsewhere, being Serious was a disaster.

Not-A Does Not Imply B

Just a thought suggested by some economic discussions I’ve followed: many people seem to have a hard time accepting that there are intermediate positions — in particular that you can question free-market, hard-money dogma without being a wild man. To say that some inflation can sometimes be a good thing does not mean advocating hyperinflation; to call for deficit spending in slumps does not mean saying that debt and deficits never matter; and so on.

This inability to make distinctions has really been on display in response to my various comments about Argentina. My point is that you can’t use Argentina to make a case that default is always a disaster, since Argentina had a strong recovery after default. I would have thought that was a clear and simple point. But apparently many people believe I am claiming that:

- Everything in Argentina is wonderful to this day.

- Everything that presidents Nestor Kirchner and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner did was right.

- Default was the sole cause of good news in Argentina.

- Everyone should immediately default.

Um, no. None of those are claims that I made.

I really do worry about the state of reading comprehension. Or maybe it’s just that extremists can’t grasp the notion of non-extreme positions held by other people.

Truthout has licensed this content. It may not be reproduced by any other source and is not covered by our Creative Commons license.

Paul Krugman joined The New York Times in 1999 as a columnist on the Op-Ed page and continues as a professor of economics and international affairs at Princeton University. He was awarded the Nobel in economic science in 2008.

Mr Krugman is the author or editor of 20 books and more than 200 papers in professional journals and edited volumes, including “The Return of Depression Economics” (2008) and “The Conscience of a Liberal” (2007). Copyright 2011 The New York Times.

Truthout Is Preparing to Meet Trump’s Agenda With Resistance at Every Turn

Dear Truthout Community,

If you feel rage, despondency, confusion and deep fear today, you are not alone. We’re feeling it too. We are heartsick. Facing down Trump’s fascist agenda, we are desperately worried about the most vulnerable people among us, including our loved ones and everyone in the Truthout community, and our minds are racing a million miles a minute to try to map out all that needs to be done.

We must give ourselves space to grieve and feel our fear, feel our rage, and keep in the forefront of our mind the stark truth that millions of real human lives are on the line. And simultaneously, we’ve got to get to work, take stock of our resources, and prepare to throw ourselves full force into the movement.

Journalism is a linchpin of that movement. Even as we are reeling, we’re summoning up all the energy we can to face down what’s coming, because we know that one of the sharpest weapons against fascism is publishing the truth.

There are many terrifying planks to the Trump agenda, and we plan to devote ourselves to reporting thoroughly on each one and, crucially, covering the movements resisting them. We also recognize that Trump is a dire threat to journalism itself, and that we must take this seriously from the outset.

Last week, the four of us sat down to have some hard but necessary conversations about Truthout under a Trump presidency. How would we defend our publication from an avalanche of far right lawsuits that seek to bankrupt us? How would we keep our reporters safe if they need to cover outbreaks of political violence, or if they are targeted by authorities? How will we urgently produce the practical analysis, tools and movement coverage that you need right now — breaking through our normal routines to meet a terrifying moment in ways that best serve you?

It will be a tough, scary four years to produce social justice-driven journalism. We need to deliver news, strategy, liberatory ideas, tools and movement-sparking solutions with a force that we never have had to before. And at the same time, we desperately need to protect our ability to do so.

We know this is such a painful moment and donations may understandably be the last thing on your mind. But we must ask for your support, which is needed in a new and urgent way.

We promise we will kick into an even higher gear to give you truthful news that cuts against the disinformation and vitriol and hate and violence. We promise to publish analyses that will serve the needs of the movements we all rely on to survive the next four years, and even build for the future. We promise to be responsive, to recognize you as members of our community with a vital stake and voice in this work.

Please dig deep if you can, but a donation of any amount will be a truly meaningful and tangible action in this cataclysmic historical moment.

We’re with you. Let’s do all we can to move forward together.

With love, rage, and solidarity,

Maya, Negin, Saima, and Ziggy