I don’t look forward to anniversaries, in large part, because I’m part of a 40-year story of extreme violence. That story in and of itself is part of a larger 500-year story that I want nothing to do with: the arrival in 1519 of Hernán Cortés to this continent; an arrival that ushered in violence that continues to this day. That 500-year anniversary is akin to the 1492 arrival of Christopher Columbus; for Native peoples, both of those years represent the introduction of physical and cultural genocide, land theft and slavery. It also has nearly the same significance for peoples of African descent.

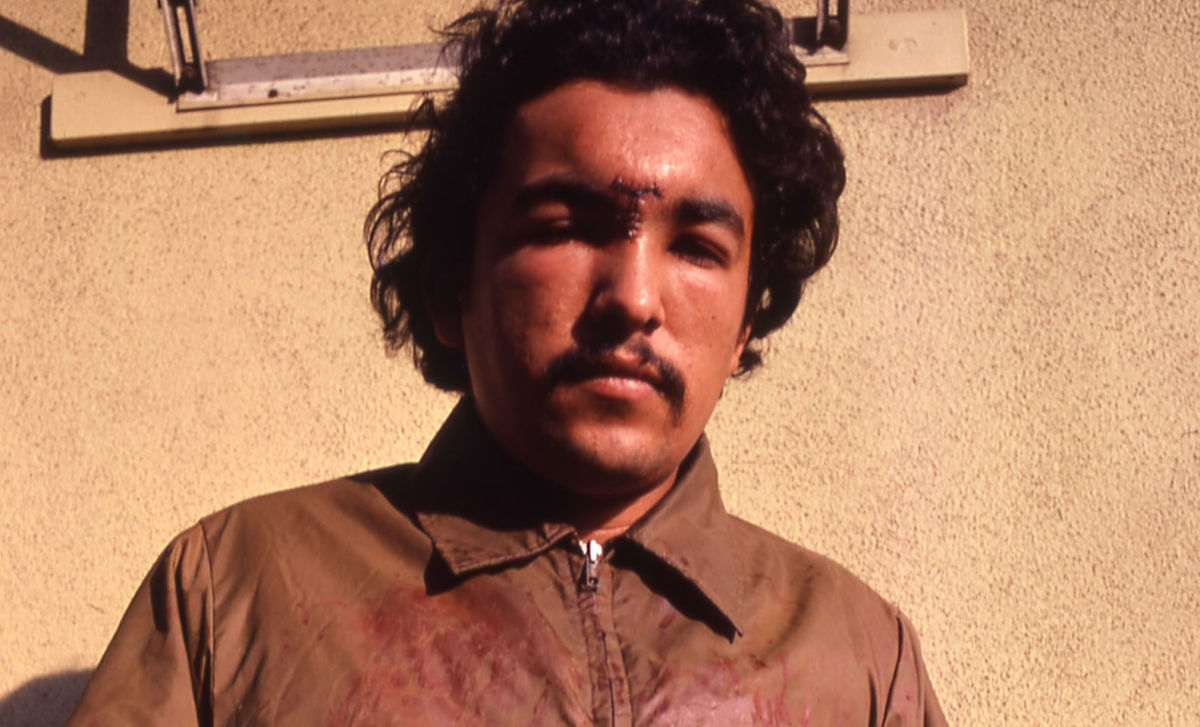

My part in this story involves surviving a near-fatal assault by four Los Angeles Sheriff’s deputies on March 23, 1979. That is the year in which my skull was fractured before I was jailed and hospitalized, threatened and charged with attempting to kill those same deputies for photographing a vicious beating in East Los Angeles by another set of 10-12 deputies. Most people of color know that law enforcement and the judicial system are part of a system of control. What made my case unique is simply that I won my trials; even to this day, victories in criminal cases of police brutality are extremely rare. The only victories are won in civil cases — not by victims, but by their families — and even those victories are extremely rare.

Anniversaries normally celebrate beautiful moments in life, but not when they involve violent trauma. About 10 years ago, I stopped commemorating March 23 because it would always trigger memories of police-perpetrated death threats, harassment and arrests — about 60 police interactions total — as well as my lengthy court battles (lasting about nine months in terms of my criminal trial), and another seven years for my ultimately successful lawsuit against the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department, respectively. I never consciously commemorated those days on purpose; they simply became ominous as the days approached, filled with traumatic memories.

Instead of commemorating those days, I began to celebrate when I won my criminal trial in November of that year. This year, however, 40 years is weighing heavily on me, and I’m not sure why. What’s the difference between seven or 40 years when it’s all in the past? The difference, as someone I’m close to says, is that it represents a lifetime. Adding to the burden of this memory is today’s ongoing and unjustified violence by law enforcement officials against migrant, Indigenous and African American women.

Because of the continual harassment, mostly by Sheriff’s deputies, I lived with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and traumatic brain injury for many years. But one adapts, even to this violent society. After being pronounced “healed” by a therapist, I have never actually been able to shake off the trauma from 40 years ago, because I have never believed that it was just me that was damaged. To this day, I know that it was the cops, their enablers and society itself that remains seriously damaged in a state of rampant impunity. And the killings and brutality continue unabated.

I have continued to monitor police abuse since those days, and precisely because I have, and because the brutality never ends, the trauma never goes away. I briefly stopped that monitoring in 2009, vowing to leave that underworld of police brutality behind, until 2014, when Michael Brown was killed in Ferguson, Missouri.

Ever since then, I have again been systematically documenting killings and brutality by law enforcement. Since then, law enforcement officers have killed more than 5,000 people, and many of these killings have been videotaped. Several sources have documented between 1,000-1,100 deaths at the hands of police per year since 2014. Yet, contrary to what many people believe, these sources show there has not been a dramatic increase in prosecutions.

During all these years, I have met many family members, spouses and siblings of people who have had a loved one killed and continue to suffer mainly from the lack of justice of the U.S. judicial system. This system of control ensures law enforcement officers live in that state of impunity in a country where the unfulfilled promise of justice for all lives within the pledge of allegiance, but seemingly nowhere else.

What I have learned through the years is that when it comes to people of color — whose skyrocketing rates of killings are vastly undercounted — our bodies and communities are racially patrolled, something that sets us apart from white people that are unjustifiably killed. This patrolling is not new, and in large part, that is why the U.S. also has the largest prison system in the world.

Do I believe in the U.S. judicial system? Absolutely not. Even if justice for all was ever achieved, the trauma to the families would not end; only when the violence, killings and the dehumanization ends, does the trauma end.

This violence and dehumanization have always been with us since the arrival of Columbus and Cortés.

One of the main reasons the Black Panthers were formed was to combat police brutality on the streets. Similar citizen patrols were formed by the Black and Brown Berets. While those movements faded away, the violence they sought to end did not. Fortunately, since Michael Brown was killed, powerful movements across the U.S. have formed to combat this illegal and out-of-control violence. In my view, only when the police and the larger criminal legal system are brought before the International Criminal Court at The Hague will that violence have any chance of ending; that is also when those traumas may begin to subside for many. Nothing short of that is a cause to celebrate, much less commemorate.

Press freedom is under attack

As Trump cracks down on political speech, independent media is increasingly necessary.

Truthout produces reporting you won’t see in the mainstream: journalism from the frontlines of global conflict, interviews with grassroots movement leaders, high-quality legal analysis and more.

Our work is possible thanks to reader support. Help Truthout catalyze change and social justice — make a tax-deductible monthly or one-time donation today.