In the fall of 1994, I was selected as a Smithsonian fellow by the Anacostia Museum to curate an exhibition on post-Harlem Renaissance artist Georgette Seabrooke Powell. By then, Powell was one of the last surviving artists of the era. My job as guest curator was to find out all I could about the artist, and create an exhibition to open in approximately six months’ time. This account of my time with Powell is one part art history paper; one part biography – Georgette’s; and one part memoir – mine. It is a holistic approach to the discussion of the artist, her community activism, and art that reflects the holistic nature of her approach to her artistry and her life.

I called Ms. Powell to schedule an appointment to see her works. Immediately she said “call me Georgette.” I’d been informed that some of her signature pieces were in her home. What an understatement. With the exception of a few works in the collections of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, several arts and education institutions, and a handful of private collectors, Georgette retained the vast majority of her paintings and mixed media works.

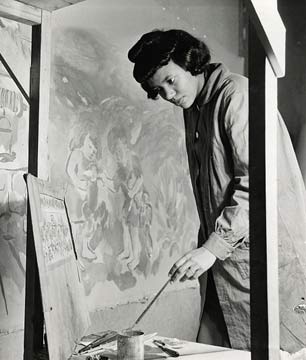

Upon entering her home in NW D.C., I saw stacks of paintings, studies, posters, articles, and artist’s materials. It was overwhelming in the best way. While examining her painting Tired Feet, an oil on canvas dated 1936, Georgette began to tell me the story of her life. Georgette Ernestine Seabrooke was born on August 2, 1916 in Charleston, South Carolina. Georgette’s father was a business owner; he came from a family whose father insisted upon financial independence from the white economic structure of South Carolina. Mr. George Seabrooke owned a hotel, and Mrs. Anna Seabrooke owned property in Charleston that Georgette inherited many years later upon her mother’s death. Mr. and Mrs. Seabrooke were late in life parents; they doted on their only child who began to read and write at age 3. Georgette’s father believed that she required educational opportunities not available in Charleston. The Seabrookes became part of the Great Migration story early on when they left South Carolina for New York City when Georgette was 4 years old.

It was a hardship for the Seabrookes, independent and financially stable in the South, to arrive in New York, the “land of opportunity,” only to become dependent upon the work demands of others and subject to wages corresponding with those demands. Mr. Seabrooke died while Georgette was in elementary school. Her mother, never having to work outside the home, became a domestic – and one who used her proximity to find out about the best schools and extra-curricular activities for her bright and talented daughter. Georgette attended the prestigious Yorkville School, where her academic excellence shone, and her artistic talent began to emerge. Georgette enrolled in the Harlem Art Workshop, and the Harlem Community Art Center where, as a teenager, she and her contemporaries including Jacob Lawrence and Romare Bearden were instructed by Charles Alston, Augusta Savage and Gwendolyn Bennett.

Georgette mastered the art of painting and printmaking. The critical yet sympathetic gaze that would become hallmark in her style of portraiture, as well as the lush colors and voluptuous forms of her signature style matured in her studies at Cooper Union where she attended at the age of 17 from 1933 to 1937. Her painting, Church Scene, an oil on canvas dated 1935, celebrates, in Georgette’s words, the joy and expression of worship. Church Scene was awarded the distinguished Silver Medal, Cooper Union’s highest honor in 1935, yet two years later the school refused to grant her degree.

Georgette Seabrooke, under the supervision of Charles Alston, began to work for the WPA (Works Progress Administration) Federal Arts Project while enrolled at Cooper Union. What should have been a mutually beneficial partnership between a group of artists creating public works and the City of New York and its hospital administration turned into a firestorm when complaints were lodged over the “depiction of Negro subject matter” in murals painted at Harlem Hospital. Charles Alston, Georgette Seabrooke, Vertis Hayes and others waged a campaign of protest, documented in correspondence between the artists who refused to give in to the demands of the city and its hospital administration, and the city of New York who wished to “whitewash” the mural project.

The Harlem Hospital muralists won. Georgette’s mural, Recreation In Harlem, completed in 1937 was situated in the Children’s Pavilion. Her intent was to create scenes that would bring happiness and a sense of familiar surroundings to children who were ill. She felt strongly that the people in those murals should represent the black community that the hospital served. The marriage between art and activism in the person of Georgette Seabrooke Powell was sealed in the hard won victory of the Harlem Hospital mural project.

Georgette, who by 1936 (and underage for hire by the WPA) had achieved Master Artist classification in the Federal Arts Project, was denied her diploma by Cooper Union the following year for – in their terms – incomplete work. Neither the award winning painting that medaled two years before nor her work with the WPA were accepted for credit. In 1997, sixty years after refusing to grant Georgette her diploma, Cooper Union invited her to campus to honor her achievements – a second effort at correcting the wrong that began with issuing her diploma several years before.

Georgette, in her New York period from 1937 to 1959, married Dr. George Wesley Powell, had three beautiful children, Wesley, Phyllis and Ric, and buried the beloved mother who so shaped her education and artistic career. She also studied Set Design at Fordham University and Art Therapy at the Turtle Bay Music School. When the Powells moved to Washington, D.C. in 1959 they bought a home from a physician that came with a medical office. George Wesley, a trained physician who became a firefighter and was one of the founders of the Vulcan Society, the organization of Black firefighters in New York, practiced medicine in the office of their home. Georgette lived in and worked out of their home after her husband’s death for many years before a brief stay in an assisted living community in Maryland, then her final move in the early 2000s to the Palm Coast, Florida home she and her husband had purchased for retirement.

There is not a lot of available artwork to show during the period between 1937 and 1959. Georgette concentrated on family. She made it first priority to focus on her home and the upbringing of her children with as much education and creative stimulus as possible. It was a decision that she did not regret, but acknowledged it might have cost her recognition on par with her friends and contemporaries such as Lois Maillou Jones and Elizabeth Catlett.

While Georgette might not have been creating works that would become latter career signature pieces during the 50s and 60s, she was very busy creating artistic opportunities for others in the development of exhibitions, workshops, arts events in public spaces, and finally the opening of the Powell Art Studio. It was a center for creativity in the visual and musical arts. Her son Ric was one of the musicians who frequented the studio; one day he brought along his friend and fellow musician Donny Hathaway, who could be seen at the Powell Studio in the early days of his career while a student at Howard University.

Georgette, always a student as well as a teacher, enrolled in Howard University and received a Bachelor in Fine Arts in 1973. Her education at Howard and related trips to Nigeria and Senegal, including her address at FESTAC (Festival of African Culture), birthed a new artistic phase in Georgette. Her mixed media works represent a sharp departure, marked by the use of fabric fragments, found materials and African textiles. These works attest to the Georgette’s refusal to stagnate as an artist, continually experimenting with new materials and new forms. Georgette also started Art in the Park in 1966, and continued to host it annually at Malcolm X Park for more than 30 years. In 1970, she founded Tomorrow’s World Art Center, the non-profit arts and education organization that reflected the artist’s philosophy of art in relation to activism. Tomorrow’s World was active for approximately 30 years.

Georgette also continued her art therapy training in D.C. at the Metropolitan Mental Health Center and the Washington School of Psychiatry. Georgette, a registered art therapist with publications in the field, became a clinical instructor then supervisor at George Washington University. In 2008, the American Art Therapy Association, the professional organization in the field, honored Georgette with its first Pioneer Award for Lifetime Achievement in Art Therapy. Evident in her painting Sister Lucy, a 1976 oil on wood, the aspects of humanity that touch us in our most vulnerable places – sadness, worry, fear, longing, despair – are brought to light in the eyes and expression of the woman who looks out at or beyond us, who fades into or emerges out of the woodwork on which she is painted.

Georgette’s compassionate critique continues in a series of mixed media portraits of the homeless. Troubled by the increasing homelessness seen on the streets of D.C. in the 70s and 80s due to shrinking mental health resources, and growing populations of war veterans and the unemployed, Georgette turned to her artwork to express her sympathy and outrage.

But for the Grace of God, the most well-known in the series on homelessness, is a superior example of the artist’s deft application of textures, graphic images, and other select materials to illustrate a powerful narrative. The homeless woman’s effort to make beauty in a world of lack is evident in her leopard print coat, the bangles on her wrists and the flower on her hat. Look closely and you might recognize the subject as Georgette Seabrooke Powell – a self-portrait she named in recognition of her understanding God’s grace as being the only thing that made her different from the women she saw on the street every day.

When I saw my friend in the summer of 2008, I was a little apprehensive. There was a large celebration for her 92nd birthday and she had invited me to stay in her home just as I had hosted her when she returned to New York and Cooper Union almost ten years before. I, now in my mid-forties, had married for the first time and separated from my then husband in three years’ time. Georgette was a woman who married early, raised three children, remained married to her husband until his death, and never married again. I never knew Georgette to be judgmental, but I worried what she would think of my brief attempt at marriage. She looked at me across the table. She was in a wheelchair now. Her speech was impeded but understandable. Her hands no longer allowed her to paint, but she continued to clip informative articles out of newspapers and cut interesting images out of magazines. The same compassionate critical gaze that she turned out onto the world for more than 70 years now rested on me. She said “You’ll be fine. We’re tough birds.” After a pause we then went on to talk about all the “woman stuff” that friends can have on their list when it’s been too long since they’ve been together.

My last call to Georgette was difficult. Her illness made our phone conversation almost impossible. Her caretaker became the interpreter through which I understood what my friend was attempting to say. Now, in the three years since her passing, I look at all the great and valuable things she taught me – some by word and some by deed. She started out for me as the subject of an exhibition; in turn, she became a teacher, role model, mentor and, most importantly, a dear and trusted friend. Her life – up to and including her death – teaches me still. I learned that the keeping is key. Keep living. Keep loving. Keep working. Keep praying. Keep praising. And always keep creating. Keep creating till the work is done. Ashe and Amen, Georgette. Your work is done.

To see more of Georgette Seabrooke Powell’s art, visit her official online exhibition.

5 Days Left: All gifts to Truthout now matched!

From now until the end of the year, all donations to Truthout will be matched dollar for dollar up to $50,000! Thanks to a generous supporter, your one-time gift today will be matched immediately. As well, your monthly donation will be matched for the whole first year, doubling your impact.

We have just 5 days left to raise $50,000 and receive the full match.

This matching gift comes at a critical time. As Trump attempts to silence dissenting voices and oppositional nonprofits, reader support is our best defense against the right-wing agenda.

Help Truthout confront Trump’s fascism in 2026, and have your donation matched now!