Part of the Series

Despair and Disparity: The Uneven Burdens of COVID-19

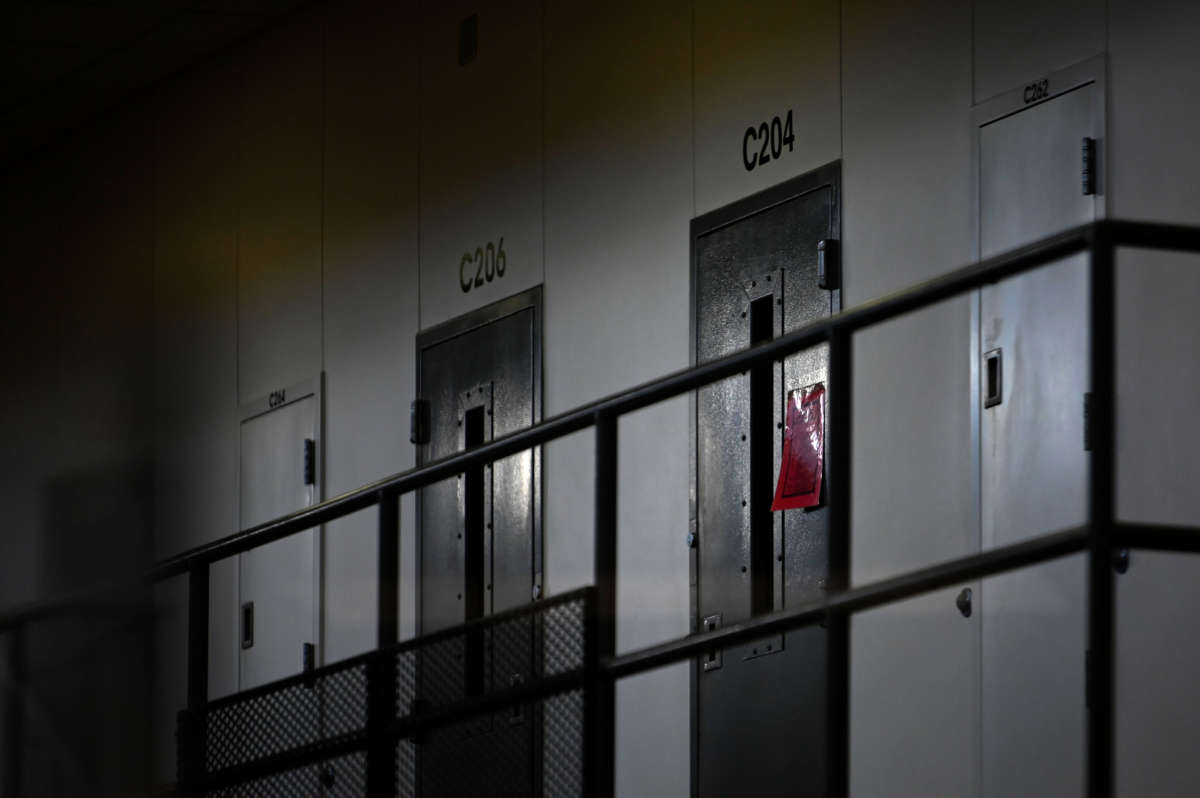

Across the globe, mask mandates are gone; airplanes, bars and sports stadiums are teeming; and governments, corporations, and bosses increasingly exhort and extort people to return to cubicles and office buildings, classrooms, and shopping malls. Yet, despite this push to return to “business as usual,” we must act to ensure that the pandemic-generated focus on prisons and jails — their deplorable conditions, the high rates of deaths, and the status quo of medical neglect — does not waver.

During the initial panic of the pandemic many nations, including the United States, were forced to recognize that prisons and jails were among the spaces hardest hit by COVID-19, the infectious disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. In April 2020, Cook County Jail in Chicago was the nation’s top COVID-19 hot spot. Federal prison populations had a rate of COVID-19 three times higher than neighboring communities.

The inherently harmful nature of incarceration made the COVID-19 pandemic even more deadly. Devon Terrell, held in Illinois’s Stateville Correctional Center and a contributor to Illinois Deaths in Custody Project’s short film about COVID-19 in prison, Letters to Lost Loved Ones, described the lethal neglect: “Months came and went before soap, bleach, disinfectant were distributed,” he said.

Horrifically, even the reported rates in these prison hot spots were undercounts. Getting accurate information about COVID-19 rates is difficult inside prisons and jails, and in fact, some prisons, jails and states refuse to even collect this data, and/or test people inside prison for the virus. This reality is reminiscent of the early days of the pandemic, when former President Donald Trump argued against letting ill passengers leave a cruise ship, saying, “I like the numbers being where they are…. I don’t need to have the [confirmed COVID-19] numbers double.” Many officials’ positions regarding infection rates in prisons and jails seems to be, if we don’t test it or count it, it didn’t happen.

As members of the Illinois Deaths in Custody Project we — a group of artists, educators and researchers — were motivated in 2016 to work collectively to gather information about all deaths in prison in our home state. Outraged by the conditions inside prison and encouraged by practices in other countries, such as mandatory independent inquests after any death in custody, we began to push for access to information.

Using public records obtained under Freedom of Information Act requests and mail, we gathered, digitized and posted online data about deaths in Illinois prisons from 2010 through 2021. At the same time, we began publishing our findings, including a comprehensive factsheet — the first public document using Illinois Department of Corrections data about deaths in custody. We aimed to increase public knowledge about deaths in prisons, but far more importantly, we worked to foster accountability from those responsible for prison conditions and grow decarceration initiatives.

Our research illustrated that illness and death in prison has always been business as usual. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, at least 80-100 people died in prison every year in Illinois, and nationally prisons are “increasingly deadly” places, according to Bureau of Justice data. Research by the Prison Policy Institute documents that incarceration arrests individual lives and “has shortened the overall US life expectancy by almost two years.”

In 2022 at least five prisons in Illinois had people with active cases of the deadly Legionnaires’ disease, yet the Illinois Department of Corrections made misleading statements about the presence of the bacteria causing the illness before finally acknowledging its spread.

It is not simply the conditions inside prisons that are deadly. People who work in prisons perpetuate harm: As documented by Chicago’s public radio podcast Motive, prison guards use violence against incarcerated people with impunity.

When the routine business of harm and death happens inside a prison, there is little transparency. Family and friends struggle to find out information about what has happened to their incarcerated loved one. When information is finally made available, usually through struggle and with pressure, it is often paltry, riddled with errors and confusing. Guards and other prison staff are rarely held accountable. There is no requirement for an independent inquest.

COVID-19 brought some mainstream media attention to death in prison. “The pandemic has only exacerbated the poor conditions that I’ve experienced for 35 years in prison” notes Henry Messenger, a writer incarcerated at Great Meadow Correctional Facility in New York. Documenting isolation, neglected health, refusal to provide needed care and violence instigated by guards, Messenger highlights the details of prisons’ business as usual that arrests lives, including during this pandemic. COVID-19 amplified that prisons have always facilitated premature death.

Organizing by loved ones, investigative journalism and the work of advocacy groups like ours has propelled some shifts. Some states have passed slightly more potent legislation that could incrementally force more transparency.

For example, in Illinois, Gov. J. B. Pritzker signed legislation in 2021 that requires prisons to notify immediate family members when an incarcerated person dies and to investigate those deaths. But why, families ask, can’t they be notified before children, parents and siblings die, such as when they become ill or are hospitalized? This legislation also has few mechanisms to enforce reporting requirements and does not mandate an independent inquest or investigation.

In this moment when a measure of public attention is still focused on COVID-19 and prison, we must also step back and keep our eyes on the wider landscape. Yes, it is important that there is transparency — all information related to our public institutions should be made fully available — but we know that transparency cannot be the end goal. In a nation with the world’s largest prison population, decarceration must be our goal.

The endless warehousing of people does not create public safety or build accountability if individuals harm one another. Instead, it fractures communities and ends lives.

In the early days of the pandemic, Indian author and political activist Arundhati Roy famously spoke about the pandemic as a “portal,” noting the pandemic created an opportunity to break with the past and imagine the world anew. How can we use the tiny portal that COVID-19 offered into a vision of a world without prisons, by laying bear the realities of death in prison? How do we keep the public’s attention on the business as usual of lethal prison conditions?

Even more importantly, how can we keep the nation’s attention on the lives, not just the deaths, of people in prison — who are always someone’s brother, mother, auntie, cousin?

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. We have hours left to raise the $12,0000 still needed to ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.