About an hour and a half east of Ghana’s capital city, Gladys Adgy stood outside a stand in Kpone waiting for an order of grilled Tilapia.

Adgy watched the screen of her cracked smartphone. A Telegram chat with a man named Raymond pulsed with messages from the New York City area, where the largest number of Ghanaians live in the U.S.

Raymond had a green card, he kept reminding her over the last 10 months, but since President Donald Trump took office, everything changed.

In America, Raymond, who is from Accra and who left in hopes of supporting his family, has started moving like someone being hunted: afraid to go outside, avoiding any knock on the door after dark. Immigration data shows that the vast majority of Ghanaians in the U.S. have a legal right to be in the country, whether with a green card like Raymond or a “stay of removal,” which is a temporary halt to a removal order by a judge.

Adgy has never left Ghana — has never even flown in a plane — but migration sits under every decision she makes. In Kpone, Adgy sleeps in a one-room apartment with her 11-year-old son; by day she picks up sporadic work as a land surveyor for a construction company or in the local market. These days, she estimates she is called into work less than 10 days a month. She has been working toward a U.S. visa since at least 2019.

“There is a lot of peace here, but there is no money,” she said, but these days she is just as scared of being deported from the U.S. as compared to how difficult of a journey it might be to get there.

On WhatsApp and Telegram in Ghana and the U.S., stories of people vanishing between immigration checks and deportation flights are rampant.

Across market stalls, law offices, and dim one-room apartments, people keep circling back to the thought of strangers — or themselves — sent off on unmarked flights, then locked away in barracks, and dragged across the floor by military personnel.

Everywhere, lives are being reordered around it — lawyers racing to military camps, an influx of deportees “lying low” in Accra, parents calculating drowning in rent and school fees in Ghana against the risk of a knock on the door in the Bronx.

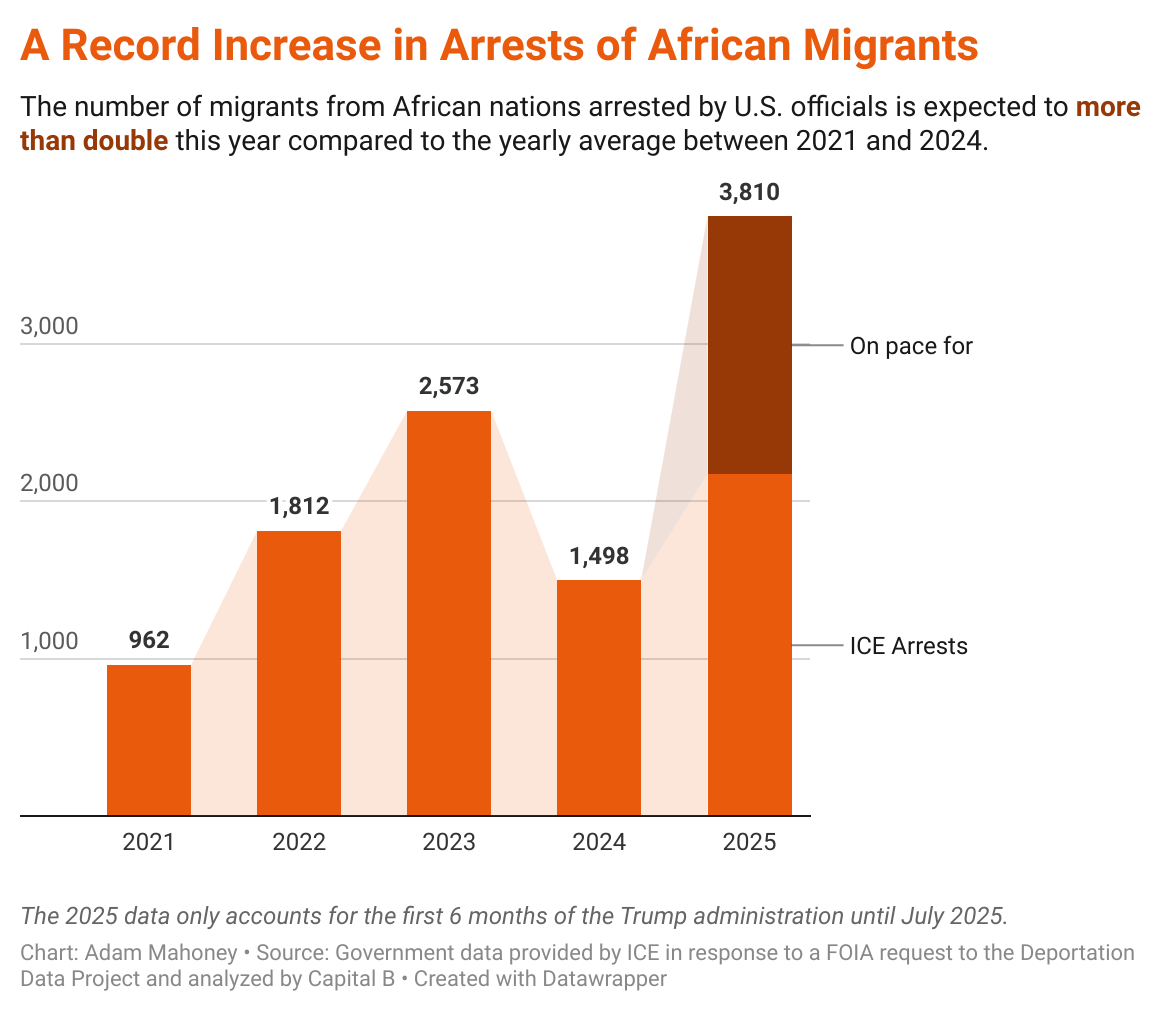

While much attention has focused on deportations of Latin American migrants, a new Capital B analysis found deportations of people from African nations are on pace to nearly triple compared to the Biden years, and the number of arrests and people held in detention centers have more than doubled this year.

That surge is colliding with a little-known deportation pact between the U.S. and Ghana that allows Washington to route West African deportees through the country — even in cases where migrants have already won legal protection — reshaping daily life from Accra to New York.

This is not due to an increase in convicted migrants: Less than 40% of African deportees this year have been convicted of a crime, our analysis of data provided by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement found.

Instead, lawyers and human rights advocates claim, the bravado behind Trump’s deportation policies is as much about removing migrants from the U.S. as it is to convince potential migrants like Adgy that it is not worth it and to convince those living in the U.S. like Raymond that they should self-deport.

During this administration, Ghanaian lawyer and activist Oliver Barker-Vormawor said African nations are supporting the disparities.

“Ghana has effectively become a conveyor belt for U.S. deportations, acting as an instrument of the U.S. government in this regard,” Barker-Vormawor said.

In November, Capital B spent time in three regions of Ghana speaking with residents, people recently deported from the U.S., and lawyers representing deportees. What we found is evidence that Ghana’s relationship with the U.S. and support for American deportation policies is reshaping the country, where two-thirds of people report wanting to migrate.

“Sometimes I feel my life is at risk here because of the lack of opportunity,” said William Yirenkyi, who migrated to the U.S. a decade ago before self-deporting because he could not legally work. He spends his days refreshing a U.S. immigration portal website, checking whether the country that once held him in a detention camp at the U.S.-Mexico border might now let him back in “legally.” His options are becoming increasingly limited after he said a group of Ghanaian police officers attacked him last year. He recently petitioned the country’s human rights office to investigate the nation’s police force.

“I think there are a lot of opportunities in America, but it is dehumanizing that these are my only options,” he said from a coffee shop in Accra while wearing an American flag T-shirt.

Camps, Courts, and Quiet Transfers

At one military camp outside the capital, deportees described being herded into a dusty, unclean hall with bare mattresses, no bedding, and no nearby toilets or running water. In another case, when lawyers from Barker-Vormawor’s firm arrived to challenge the removals, they watched as officers spent nearly an hour trying to wrench one woman out of the lobby; at one point she clung to his leg while they dragged her across the tile toward a waiting van, gasping for air as he dug through her bag for an inhaler during an asthma attack.

Sometime around then, another deported woman attempted to take her own life, according to attorney Ana Dionne-Lanier. Dionne-Lanier’s own client, who was held in the same camp, reported that the incident occurred while detainees were being interviewed by officials attempting to remove them to their countries of origin.

Dionne-Lanier’s client — who had previously won a legal right to stay in the U.S. due to a credible fear of torture — was recently removed from the Ghanaian camp and flown back to his home country, where he is now hiding at a friend’s house to escape the persecution he originally fled.

Under the deportation agreement between Ghana and the U.S., Ghana is aiding America in deporting West Africans after their home countries, like Nigeria and Togo, have refused to take them.

People — many of whom have lived in the U.S. for decades and have already won asylum or other protection — are flown to Ghana, held in military camps and guarded hotels, and in many cases pushed onward to countries they fled years ago, despite court orders meant to shield them from torture or persecution. As of late November, over 40 West African deportees had moved throughout Ghana.

Capital B reached out to Ghana’s Immigration Service and the office of the Ministry for Foreign Affairs, but did not receive a response.

For Nana Kwesi Osei Bonsu, a land and environmental defender now seeking asylum in Ohio, Ghana is not the “safe” country U.S. officials describe. A seventh-generation descendant of the Indigenous peoples of Ghana — the Ashanti Empire — he built a nonprofit to protect his community’s ancestral lands from powerful encroachers, including American and Chinese foreign investment companies, he said. In return, he said, he was criminalized, tortured in police custody, and forced to flee.

“The Ghanaian government has actually failed to protect some of its own citizens,” he said. “So what credibility will they have to protect other countries’ nationals through these agreements?”

Ghanaian leaders have defended the deal in the language of Pan-Africanism — a global movement to build unity, solidarity, and liberation for people of African descent everywhere — saying they’re taking the migrants to protect them from the U.S. detention system. At the same time, the government has quietly celebrated the agreement because it will lower visa restrictions for Ghanaians traveling to the U.S. and relax U.S. tariffs on the country.

“These agreements make African governments partners in the Trump administration’s horrifying violations of immigrants’ human rights,” said Allan Ngari, Africa advocacy director at Human Rights Watch. The African governments, he said, were potentially “violating international law.” U.S. and international law prohibits the government from returning individuals to places where their life or freedom would be threatened.

That contradiction is obvious to people like Osei Bonsu. From the front seat of his car in Cleveland, where he drives Uber and Lyft up to 15 hours a day and often sleeps between shifts, he juggles calls with lawyers in Ghana and prepares filings for U.S. immigration court. He is caught between two governments: one that once tortured him and another that could still send him back.

“What brought me to the United States is the rise of authoritarianism and persecution,” he said. “And the price that came with [immigrating to the U.S.] has been the same.”

On social media and in Ghana’s streets and markets, meanwhile, public sentiment about the agreement is largely negative. Not due to concerns of human rights violations like advocates have argued, but because of Trump’s talk of only “criminals” and “bad people” being removed. The assumption is that these deportees, including the record-number of Ghanaians deported this year, must be violent and will bring crime to the nation.

However, the majority of deportees convicted of crimes were arrested for financial crimes such as check forgery or selling stolen or counterfeit goods, according to Capital B’s analysis.

“You would think that [our own economic struggles] would create some sort of empathy for persons who are caught up in this situation,” said Barker-Vormawor. “But there is no sense of solidarity.”

Barker-Vormawor’s organization, Democracy Hub, has sued the Ghanaian government, challenging the agreement for violating Ghana’s constitution. The case is being heard before the Ghanaian Supreme Court.

This is not the first such deportation deal: Ghana previously signed at least two controversial removal arrangements with Washington. Under the Obama administration in 2016, Ghana agreed to receive two Yemeni men released from Guantánamo Bay and then deported, and two years later it entered another deal to take a backlog of thousands of Ghanaians facing deportation in exchange for lifting U.S. visa sanctions.

Despite the uptick during this second Trump administration, U.S. policies show clear racial disparities: During the Biden administration, Black migrants were deported at a rate four times more often than their numbers would suggest.

Ghanaian officials “are so blinded by this need to be in the good books of the U.S. that we haven’t even reckoned with the toxic, racialized undertones of these removals,” Barker-Vormawor said.

When Pan-Africanism Meets US Deportation Policy

As a child, Richard Tetteh Martey said he would watch planes trace paths across the sky and imagine a “better future out there,” somewhere the system worked in ways he had only heard about from relatives abroad. But today, for the 27-year-old Ghanaian and recent college graduate in mechanical engineering, these dreams and the deportation deal sit alongside another set of choices that have reshaped Ghana’s place in the Black imagination.

Launched in 2019, Ghana’s “Year of Return” campaign invited people of African descent, especially Black Americans, to visit and settle in the country as a way to reconnect with the continent and boost tourism and investment. Officials have celebrated its success: Hundreds of thousands of visitors arrived that year and thousands of Black Americans are estimated to have relocated permanently, many of them concentrating in Accra and nearby coastal areas.

But the influx of relatively wealthier diaspora residents has collided with long-standing housing shortages and speculative real estate development, sharply raising prices and displacing lower-income Ghanaians from central Accra.

In Osu, a popular neighborhood in Accra for Americans, monthly rental prices have jumped to $1,100 — almost five times the regional average monthly income of $245.

In the vegan café where Tetteh Martey works, he said most customers can now afford things he cannot: the smoothies he blends and the new condos across the street. For Tetteh Martey, it feels like a one-way arrangement: Ghana opened its doors, rolled out the red carpet, and rebranded neighborhoods for diaspora investors, while the U.S. is tightening its borders and expelling other Black migrants back the same route.

“It is quite concerning that we are welcoming people from the U.S. into our home, and they don’t want to reciprocate,” he said. “Someone with my qualifications from America can live here comfortably; I cannot.

From Accra to the Bronx, Ghanaians Are Searching for Safety

In early October, Martin Berchie boarded a plane in Minnesota, shackled. He had lived in the U.S. for years and purchased a home with his wife just the year before, but during a routine immigration check, ICE arrested him. A federal judge recommended his release. But ICE obtained travel documents from the Ghanaian government anyway.

In a court filing, Berchie alleged that ICE agents put his name on a travel document that was already used for a different detainee who had already been deported. Once back in Ghana, ICE officials “abandoned” him at the airport, he said, and then Ghanaian immigration officials “rejected” his return to the country because of the paperwork issue.

It was “akin to pushing Berchie out of a helicopter with a parachute,” his lawyer Nico Ratkowski wrote in the legal filing. Eventually, Ghana officials “had no other choice” but to process Berchie into Ghana, where he is now “lying low,” he said during a phone call with Capital B.

Yirenkyi knows the math differently. He crossed the U.S.-Mexico border in 2013, spent a month in immigration detention, got paroled, married an American woman, then returned to Ghana voluntarily when the marriage fell apart. Now 36 and enrolled in his first year of university, he is waiting on a new visa application that feels increasingly futile.

“I would say 90% of the people want to leave,” Yirenkyi said flatly. “Not because of anything but because of socioeconomic conditions. No jobs, health care system, our roads, housing deficit.” Yet when asked about Trump’s deportation policies, he surprisingly responded with measured agreement for someone who once illegally immigrated: “I believe in people being given a fair hearing. If you get your fair hearing and you don’t pass, then you’re supposed to leave.”

What he cannot accept is deportation to places where people fear harm.

“Everybody has the right to safety,” he said.

But these days, safety is hard to find for Ghanaians, no matter where they are.

In New Jersey, Raymond is still stuck in his apartment.

In Ohio, Osei Bonsu is spending his nights in a parked car drafting legal briefs to defend the burial grounds of his ancestors back in Ghana.

In Kpone, Adgy is still dreaming of America while living on a few dollars a day.

And somewhere in Accra, Berchie is suspended between two countries that have both claimed they cannot keep him.

In the split-screen between welcome and removal, Ghana stands as both haven and holding pen, said the lawyer, Barker-Vormawor — “a mirror for the world’s uneven humanity.”

Media that fights fascism

Truthout is funded almost entirely by readers — that’s why we can speak truth to power and cut against the mainstream narrative. But independent journalists at Truthout face mounting political repression under Trump.

We rely on your support to survive McCarthyist censorship. Please make a tax-deductible one-time or monthly donation.