“What happens to a dream deferred?” asks Langston Hughes in “Harlem.”

As a poem of social consciousness, “Harlem” may often be reduced to literary analysis or an artifact of the Harlem Renaissance; as schools become more and more focused on the Common Core and raising scores on the related next-generation tests, the poem is likely to be (if at all) just one more text for close reading practice.

But on MLK Day in 2014, “Harlem” remains a powerful and necessary question—and a disturbing harbinger, as Hughes answers his opening question with more questions:

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore—

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over—

like a syrupy sweet?Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.Or does it explode?

In her “Diving into the Wreck,” Adrienne Rich explores a personal and social wreck, confronting “the wreck and not the story of the wreck/the thing itself and not the myth.” She concludes with a recognition that echoes a recurring theme found in Hughes, Ralph Ellison, and countless artists aware of otherness, invisibility:

We are, I am, you are

by cowardice or courage

the one who find our way

back to this scene

carrying a knife, a camera

a book of myths

in which

our names do not appear.

The history students have been and are currently taught remains a controlled, if not contrived, story; where once many “names [did] not appear”—names of African Americans, names of women, names of anyone from the “the deliberately silenced, or the preferably unheard”—now students are presented with a version of names that serves to keep Hughes’s question in “Harlem” relevant, not only as a dream deferred, but also as a dream ignored.

Students will certainly discuss King in these days around his birthday and holiday; and students will likely, as noted above, be lead through “I Have a Dream” as a text ripe for close reading, possibly also analyzing “Letter from Birmingham City Jail” for its technical precision but not its call for civil disobedience in the face of inequity.

Few students will be asked to look behind the official view of King as the passive radical, a masking narrative used to controlwhose name is allowed into the “book of myths” as well as how students are allowed to see those names—a pattern repeated in the life and death of Nelson Mandela:

Chris Harris captures the moment Nelson Mandela is released after serving 27 years in prison. Times photographer, Chris Harris

Education, in this era in which the dream is ignored, you see, is about rigor, “no excuses,” and (above all else) raising test scores—as our leaders chastise us about why the U.S. pales in comparison to the rest of the world: “We talk the talk, and they walk the walk.”

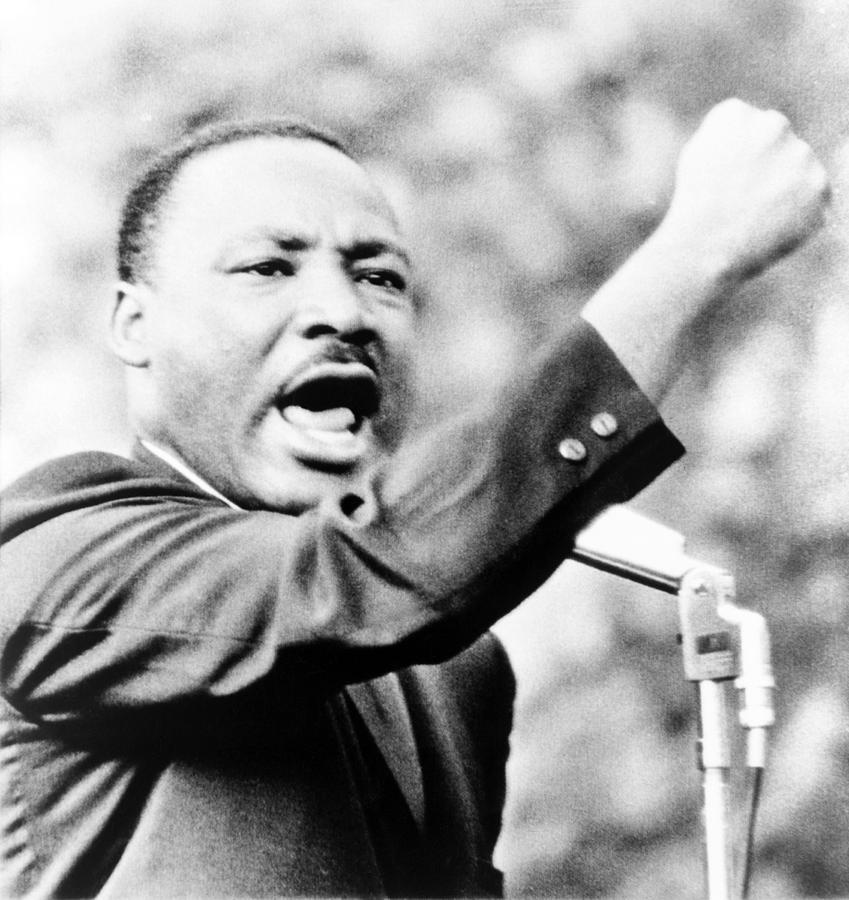

Education is not about raising fists:

If education were about raising fists—a social contract with a people’s children that every person matters, that every voice has equal volume, that equity of opportunity is the essential element of human dignity—MLK Day would include the King of The Triumph of Conscience, read for his messages and calls to action and not as a close reading activity.

If education were about raising fists, names would be added to the “book of myths,” no longer ignoring the echo of James Baldwin‘s power during the Civil Rights movement that tends to be reduced to repeatedly published images of King walking arm in arm with white men to his left and right:

But education in the U.S. is not about raising fists, and the great disturbing irony is that political leaders who are shaming the people of this country for talking the talk, but not walking the walk are themselves masters of only talking the talk.

On this MLK Day 2014, then, there remains much of King unexplored, and the days and weeks around his birthday and holiday are ideal for reading and listening to King with both reverence for his sacrifices and seeking ways in which to fulfill the dream.

But we must move beyond the ceremonial, and we must expand the “book of myths.”

And we must raise Hughes’s existential questions along with asking the truly hard questions about mass incarceration and in-school academic and discipline policies that are destroying the dreams of hundreds of thousands of young African American men week after week after week.

Where are the voices and where is the political will, we must ask, that will confront that white males outnumber African American males in the U.S. about 6 to 1, but that African American males outnumber white males about 5 to 1 in our prison system—an incarceration machine that dwarfs prison systems in countries against which political leaders use to shame the U.S. public.

In 2004, Rich called for including Baldwin in the “book of myths,” highlighting his words from “Lockridge: ‘The American Myth’”:

The gulf between our dream and the realities that we live with is something that we do not understand and do not wish to admit. It is almost as though we were asking that others look at what we want and turn their eyes, as we do, away from what we are. I am not, as I hope is clear, speaking of civil liberties, social equality, etc., where indeed strenuous battle is yet carried on; I am speaking instead of a particular shallowness of mind, an intellectual and spiritual laxness….This rigid refusal to look at ourselves may well destroy us; particularly now since if we cannot understand ourselves we will not be able to understand anything. (p. 52; Baldwin, 1998, p. 593)

Let’s place before our students, then, King metaphorically arm in arm with Baldwin—the King of The Triumph of Conscience, decrying the tragedy of Vietnam and the failure of enormous wealth turning a blind eye to inexcusable poverty, and the confrontational Baldwin, like Hughes, offering words that remain relevant today:

The truth is that the country does not know what to do with its black population now that the blacks are no longer a source of wealth, are no longer to be bought and sold and bred, like cattle; and they especially do not know what to do with young black men, who pose as devastating a threat to the economy as they do to the morals of young white cheerleaders. It is not at all accidental that the jails and the army and the needle claim so many, but there are still too many prancing around for the public comfort. Americans, of course, will deny, with horror, that they are dreaming of anything like “the final solution”—those Americans, that is, who are likely to be asked: what goes on in the vast, private hinterland of the American heart can only be guessed at, by observing the way the country goes these days. (No Name in the Street; Baldwin, 1998, pp. 432-433)

“The truth is” what will set you free.

“The truth is,” we can’t handle the truth, and “[t]his rigid refusal to look at ourselves may well destroy us.”

References

Baldwin, J. (1998). James Baldwin: Collected essays. New York, NY: The Library of America.

Rich, A. (2009). A human eye: Essays on art in society 1997-2008. New York, NY: W.W. Norton and Company.

We have 10 days to raise $50,000 — we’re counting on your support!

For those who care about justice, liberation and even the very survival of our species, we must remember our power to take action.

We won’t pretend it’s the only thing you can or should do, but one small step is to pitch in to support Truthout — as one of the last remaining truly independent, nonprofit, reader-funded news platforms, your gift will help keep the facts flowing freely.