To me, celebrating Black History Month means honoring the importance of Black knowledge production and emphasizing the deep and enduring themes of Black life, from structures that continue to oppress Black people to courageous forms of political and existential resistance. With this understanding in mind, I think it is crucial that we focus on critical race theory (CRT) and its founder, Derrick Bell, who in 1971 became the first Black tenured professor at Harvard Law School.

Today, there are many distorted characterizations of CRT and attacks against its study. Far right activist Christopher Rufo has championed this assault, arguing that CRT is “being weaponized against the American people.”

Clearly, many of the field’s current critics have no idea, no clue, about the true meaning of CRT, which consists of indispensable scholarship produced to rigorously conceptualize and fight against systemic forms of racism. Indeed, CRT is absolutely necessary to heal this fragile democracy.

To seek clarity here, I turn to the important philosophical work of Tim Golden, visiting professor of philosophy at Whitman College in Walla Walla, Washington. Golden brings clarity to bear upon the meaning of CRT and some of its critical and central insights. He is the editor of Racism and Resistance: Essays on Derrick Bell’s Racial Realism, and his most recent book is entitled, Frederick Douglass and the Philosophy of Religion: An Interpretation of Narrative, Art, and the Political.

George Yancy: In their important book, Critical Race Theory: An Introduction, Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic argue that critical race theory (CRT) emphasizes the point that “racism is ordinary, not aberrational … the usual way society does business, the common, everyday experience of most people of color in this country.” They also point out that “our system of white-over-color ascendancy serves important purposes, both psychic and material, for the dominant group.” The “critical” in critical race theory reveals just how racism is not exceptional, but a powerful force that is embedded within the legal and political operations of quotidian life. Moreover, they critically point to what W.E.B. Du Bois referred to as the “psychological wages of whiteness,” and the material affordances that racism produces. CRT uncovers what many don’t want to see or refuse to see. In this regard, CRT provides a powerful critical and emancipatory framework for thinking about racism in the U.S. Elaborate on how you understand CRT in terms of its critical and emancipatory aims.

Tim Golden: Your use of the word “emancipatory” is compelling in that CRT is engaged with American history, in particular the history of American chattel slavery. Before elaborating on this point, it is important to note that there are various iterations of CRT, which relate to different ethnicities who find themselves at the bottom of the “white-over-color ascendancy” (racial hierarchy with whites at the top) that Delgado and Stefancic reference in the lead-up to your question. For example, there are Asian, Latinx and Indigenous forms of CRT. And there is also an African American iteration, which is the one that I will be discussing here.

Again, your use of the word “emancipatory” resonates with American history and its enslavement of Black people, and hearkens back to the formation of the American republic and its central founding document, the United States Constitution. Drafted in 1787 and eventually ratified through a series of compromises that maintained slavery for the foreseeable future — at least until 1808 — CRT, in its African American iteration, with Derrick Bell as its principal expositor, has argued that those compromises set in motion a machinery of government that is dangerously and perpetually compromised in its tolerance of anti-Black racism. CRT’s critical and emancipatory aims, then, are to show how American law and politics maintain systems of racial oppression.

CRT does this in at least two ways. First, by showing how the compromises at the American founding have set the tone for a morally lax American political ethos which benefits African Americans, not because of any genuine recognition of moral harm done to them, but rather because their interests coincidentally converge with those of American whites. This is what Bell referred to as “interest convergence,” and it is a sort of utilitarian moral calculus less concerned with doing what is right and more concerned with doing what is expedient.

For example, President Abraham Lincoln, Bell would argue, did not emancipate — there’s that word again — the slaves because it was morally right, but rather because the Union had to be restored. And President Barack Obama was not elected because America had suddenly become any less racist in its view of Black people, but rather because so many upper-middle class whites were bleeding large sums of money from their retirement accounts in the financial crisis of 2008, and because Sen. John McCain and Gov. Sarah Palin appeared to them to be incompetent to handle the fledgling economy. I have written of this in the introduction to my book on Derrick Bell.

A second way that CRT advances its critical and emancipatory aims is through a trenchant critique of abstraction in American constitutional law. CRT, through the work of Bell and others, has demonstrated how the 14th Amendment of the Constitution, ratified for the purpose of helping newly freed slaves shed the legacy of slavery, is now interpreted in ways that make such remediation illegal. CRT points out how, through an abstract understanding of “equality,” liberal democratic theory, with its emphasis on a symmetrical concept of “rights,” generates absurd notions of “reverse racism,” in which whites can now claim legal harm pursuant to a constitutional amendment that was ratified, not to protect whites, but rather to remediate the harm that whites have done. CRT’s work in law is thus critical and emancipatory in its exposure of racial oppression in American constitutional law.

When teaching about racism, many of my students (especially my non-Black students) understand it as an exclusively intentional and conscious phenomenon. This, of course, implies that racism is episodic and something only “intentionally mean” people express. To help those who interpret racism in this way, can you talk about how CRT addresses the systemic nature of racism, and how unconscious racism is understood?

Reducing racism to acts of intentional conduct is an inauthentic evasion of history. Considering this point, I think it is more appropriate to call individual acts “bigoted,” as racism is not an individual action akin to theft, robbery or murder. Instead, racism is an institutional and historical phenomenon in which whites partake, often unconsciously, and in ways that reinforce racism rather than ameliorate it.

Consider my experience as a criminal defense lawyer in Philadelphia, some 20 years ago. I was in court, donning a suit, white shirt, muted tie, wearing oxford, wing-tipped shoes and carrying a black briefcase. I arrive in court and, knowing who I am and why I am there, confidently approach the bailiff in the courtroom to check the status of my case which was scheduled for trial that day, only for the bailiff to look at me and say, “no defendants allowed until 9 am.” As I tried to correct the bailiff, he stated it again more forcefully: “No defendants allowed until 9 am!” I calmly backed away until the time of the docket call when the judge took the bench and called my case. Then, I confidently approached the bar of the court and said, “Good morning, your honor, Timothy J. Golden, Esquire, for the defendant.” Shocked and humiliated, the bailiff would later apologize, and I accepted his apology.

The fact that the bailiff was mistaken about my role in court that day, even that he apologized, does not relieve him of the moral accountability for assuming I was the one charged with committing a crime. Rather, it shows how important it is, not to address so-called “mean” or “intentional” conduct from whites, putting the onus on Black people to “prove” whites are racist, but to address the unintentional conduct of whites, putting the onus on them to be aware of how quotidian interactions occur against the backdrop of a history of the white gaze, laden with all manner of potential for real harm to Black people, including mistaking attorneys for criminal defendants or mistaking Black people for criminals because of their mere presence in certain areas at certain times of the day.

Explain why CRT is a necessary discursive and activist force in 2025. What does its necessity teach us about the entrenched nature of racism in the United States?

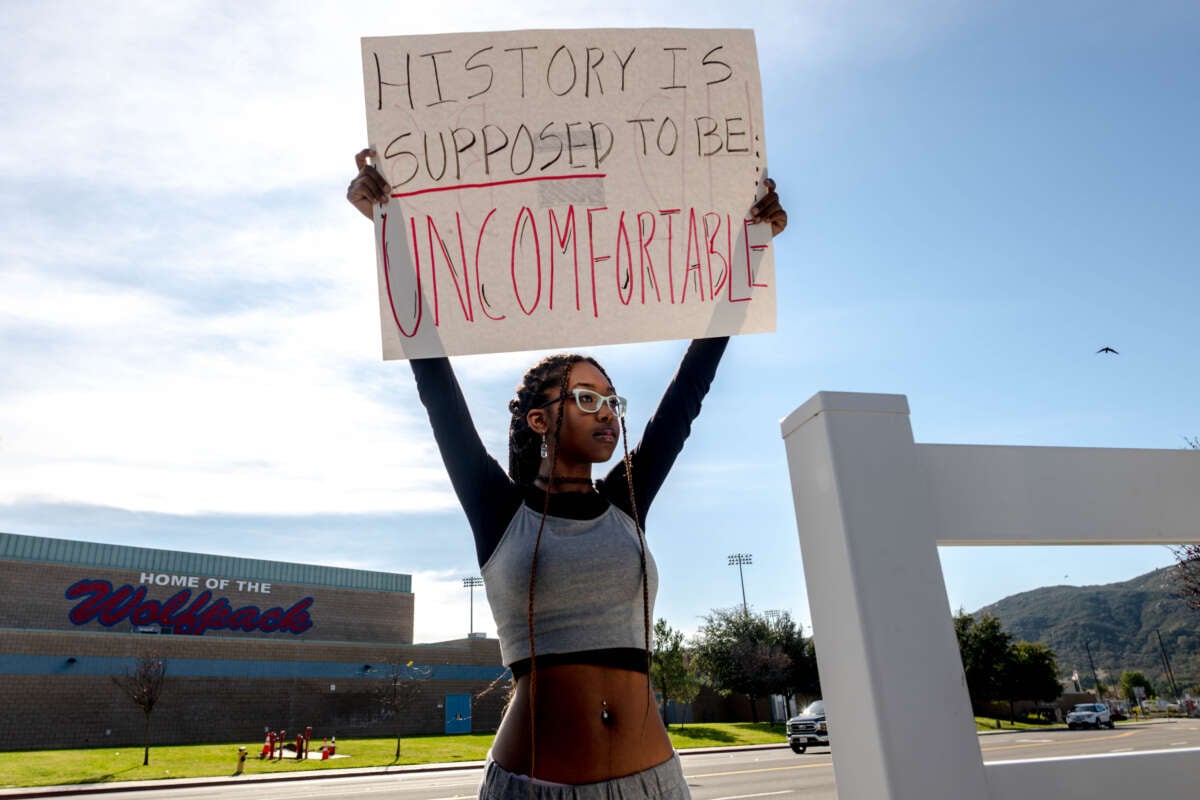

CRT is a necessary discursive and activist force in 2025 because its notions of interest convergence, its commitment to counternarratives, the value it places on political protest, and its trenchant critique of liberal democratic theory are all badly needed today. For example, in the wake of George Floyd’s murder nearly five years ago, there was lots of discussion about race-conscious initiatives such as diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) that were designed to stem the tide of institutional racism. But here we are just a few years later, inaugurating a new President with new values, and DEI is on the chopping block, with many of the companies in the private sector who had committed to it now backing away. When politics changes, so do our priorities. CRT and its insights are thus as needed now as ever before. Why? Because racism is resilient and thus still relevant. As long as there is racism, there will be a need for CRT.

Speaking of the entrenched nature of racism in the United States, Derrick Bell argued that “Black people will never gain full equality in this country.” This statement seems to contradict what I see as the emancipatory dimensions of CRT. And yet, Bell goes on to say, “The fight itself has meaning and should give us hope for the future.” Help us to unravel these two apparent oppositional claims.

This is Bell’s thesis of “racial realism,” consisting of the permanence thesis, which is that racism is permanent, and the resistance thesis, which is that a perpetual struggle against it is not merely necessary but also is deeply meaningful. Bell’s thesis of racial realism is the subject of my 2022 book, Racism and Resistance, Essays on Derrick Bell’s Racial Realism.

I think one can make sense of these seemingly contradictory claims by pointing out the fact that struggle itself is meaningful. Bell likens his notion of moral struggle in this sense to a recovering alcoholic. To remain sober, alcoholics must admit that they will always be alcoholics, for if they consider themselves to be recovered, their assurance makes them vulnerable to a relapse. But if they always consider themselves alcoholics, they retain a vigilance about their disease and are thus less likely to backslide. For Bell, the assertion that there will always be racial oppression against Black people in America is an inductive claim with the same sort of intuitive force as the claim that “the sun will rise tomorrow.” Indeed, no one can know for certain if the sun will rise tomorrow. But it would be foolish to cancel all of one’s plans for tomorrow because of such inductive uncertainty. A lesson to be learned here is that as probabilistic and inductive that the claim about tomorrow’s sunrise may be, it is certain enough for us to plan and prepare accordingly.

Such is the case with anti-Black racism in America: No one knows for sure whether anti-Black racism is permanent. But we have sufficient evidence to believe that it is permanent and can thus plan accordingly. And it would be reckless for Black people in America to have no plan to combat racism, just as it would be reckless to cancel tomorrow’s plans because of the possibility that the sun will not rise.

With this in mind, part of that plan is struggle — a struggle that, for American Black people, is ongoing. Whites can often enter an inauthentic mode of being in which they clamor for the “end” of racism. But what is really going on here? To claim that one day, anti-Black racism will be no more is problematic for two reasons. First, it defers a “solution” to an unknowable tomorrow, while doing nothing about the anti-Black racism of the present. And second, in doing so, relieves whites of any responsibility to engage in the struggle for justice in the present. What is easier: a deferral of justice to a distant future, or a radical engagement in a struggle for justice in the bloody mess of the present? Bell’s notion of struggle is, then, deeply meaningful as it enables an authentic and likely perpetual struggle against injustice. Is this comfortable? No. But it is deeply moral and meaningful.

For you, how do we keep the insights of CRT alive, especially within a context where there is so much pushback against, misinformation about and weaponization of CRT? I ask this realizing that the American experiment in “democracy” is fragile, and its maintenance is deeply at stake.

CRT has the longevity of its devotees. The more people who understand what CRT is and how it works toward a more just world, the longer CRT endures. May those who understand CRT strive, in all venues, to clarify its purpose, ensuring that others understand CRT as a servant rather than as an impediment in the cause of justice.

Our most important fundraising appeal of the year

December is the most critical time of year for Truthout, because our nonprofit news is funded almost entirely by individual donations from readers like you. So before you navigate away, we ask that you take just a second to support Truthout with a tax-deductible donation.

This year is a little different. We are up against a far-reaching, wide-scale attack on press freedom coming from the Trump administration. 2025 was a year of frightening censorship, news industry corporate consolidation, and worsening financial conditions for progressive nonprofits across the board.

We can only resist Trump’s agenda by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

We’ve set an ambitious target for our year-end campaign — a goal of $133,000 to keep up our fight against authoritarianism in 2026. Please take a meaningful action in this fight: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout before December 31. If you have the means, please dig deep.