With the rise of the right internationally, there has never been a more pressing need for clarity about the roots of fascism, its history, and why and how it can be defeated.

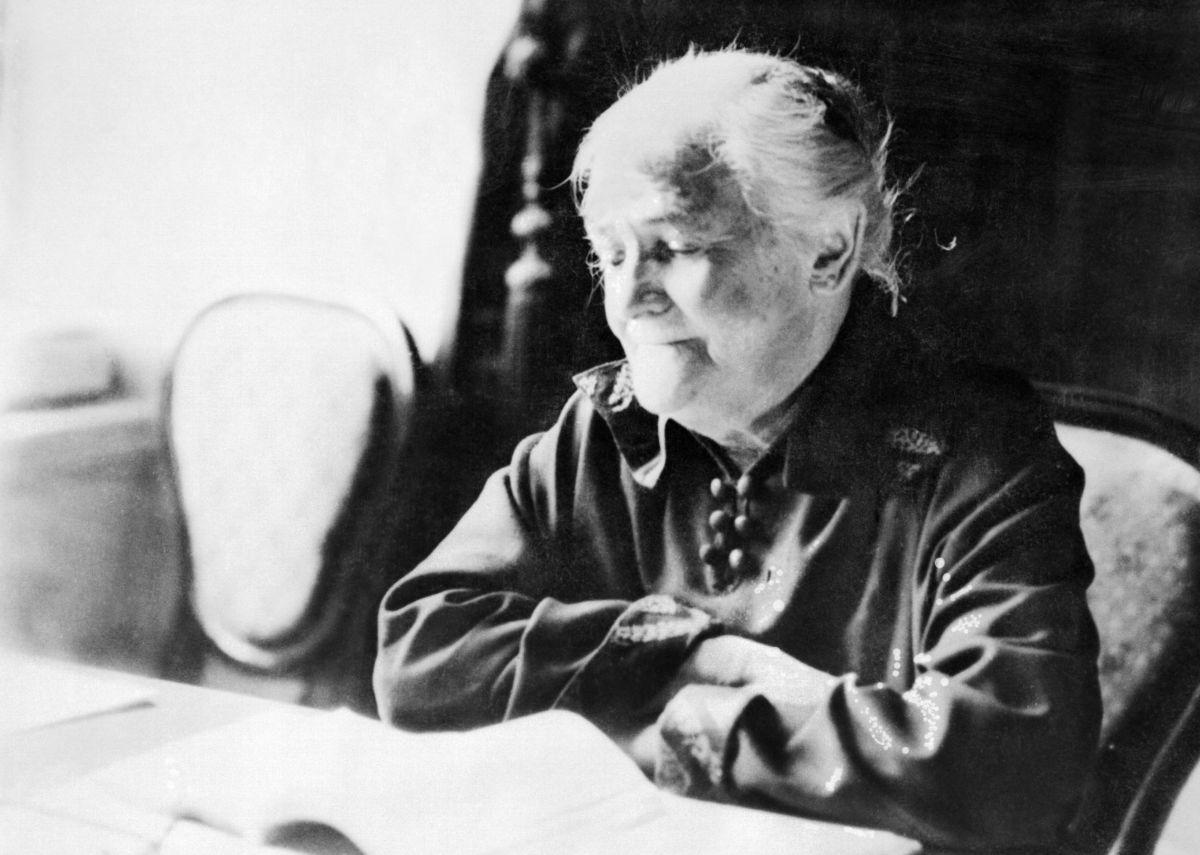

Among the clearest thinkers on this subject is German socialist Clara Zetkin, whose writing on the topic has been republished thanks to the work of Mike Taber, John Riddell and Haymarket Books.

Fighting Fascism: How to Struggle and How to Win brings to today’s audience Zetkin’s important insights on the character of fascism, its relationship to capitalism, and the most effective way for the socialist movement to defeat it.

A leading member of Germany’s Social Democratic Party (SPD) until 1917, when she participated with Rosa Luxemburg in the founding of what would become the German Communist Party, Zetkin is well-known on the left for her Marxist analysis of women’s oppression and helping to found International Women’s Day in 1910.

Within what was one of the largest socialist parties of the time, the SPD, she served as editor of Die Gleichheit (Equality), a publication aimed at women workers.

Alongside Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, Zetkin was part of many of the key debates within the SPD, including those with another leading member, Eduard Bernstein, which pitted the socialist vision of a revolutionary transformation of society against Bernstein’s idea that socialism could be achieved by a series of reforms.

Zetkin’s struggle against reformism within her party continued in the lead-up to the First World War, as she argued along with a revolutionary minority for the SPD to take a strong anti-imperialist position, including opposition to colonialism and the arms race, and a call for mass action to block the coming war.

She made her argument in the pages of Gleichheit and organized an international women’s peace conference in Switzerland, where she made the case for workers uniting against the war and their own rulers across international borders.

Zetkin, Luxemburg and Liebknecht lost these debates about war within the SPD. Instead of leading opposition to war, the SPD stood with Germany’s ruling class to send the German working class into the slaughter. Zetkin and her comrades formed the Spartacus League, which would later become a central component of the KPD, founded in 1918.

In January 1919, in response to a left-wing uprising, the German chancellor, a member of the SPD, ordered the German Army and right-wing military units of the Freikorps — the forerunner of the Nazis — to arrest the leaders of the revolt. Luxemburg and Liebknecht were captured, tortured and executed.

The downfall of Germany’s monarch, the Kaiser, in November 1918 opened up years when a socialist revolution like the one that had taken place in Russia was a real possibility. Tragically, the revolution was defeated.

The socialist left then had another terrifying development to come to terms with — the dark sprouts of fascism taking root in Europe. This became one of Zetkin’s greatest battles, one deserving further recognition for her analysis of fascism’s early incarnation in Italy and her commitment to building an opposition to fascism on a world scale.

***

Writing in 1923 on the heels of the rise to power of dictator Benito Mussolini in Italy, Zetkin makes clear in the opening pages of Fighting Fascism that this counterrevolutionary movement is a new phenomenon, different from the regular terror of the capitalist class:

It is not at all the revenge of the bourgeoisie against the militant uprising of the proletariat. In historical terms, viewed objectively, fascism arrives much more as punishment because of the proletariat has not carried and driven forward the revolution that begin in Russia. And the base of fascism lies not in a small case, but in broad social layers, broad masses reaching even into the proletariat.

We must understand these essential differences in order to deal successfully with fascism. Military means alone cannot vanquish it, if I may use that term; we must wrestle it to the ground politically and ideological.

Fascism, Zetkin argues, is fundamentally different from the capitalist response to workers’ attempts at taking power — it is more than just counterrevolutionary acts of violence and terror. This analysis stood in sharp contrast to the reformist social democrats that Zetkin was arguing with at the time.

Zetkin looked at the Italian example, where workers’ revolt inspired by the Russian Revolution of 1917 took off, reaching a high point in 1920 with workers seizing factories, occupying them, and forming workers councils to run them and armed workers’ groups to defend them.

The factory council movement spread throughout Italy, with soldiers and peasants also joining the struggle. It began to look like a revolutionary takeover by workers was possible.

Unfortunately, the organization that could have helped take this struggle further, such as the Socialist Party and the trade unions, didn’t succeed in doing so. The tide of revolt was turned back, and the workers were demoralized.

In the wake of this near-seizure of power, workers’ organizations were left weakened and vulnerable to attack. Fascists, with the backing of sections of the ruling class and the police, were able to take the initiative, terrorizing and killing thousands of workers and peasants and attempting to destroy workers’ organizations.

Mussolini and the fascists came to power in 1922, and proceeded to destroy workers’ organizations completely.

***

In her writing in 1923, Zetkin was the first to sound the alarm about this new phenomenon, expose its character and argue how to defeat it. After she identifies that fascism is something new, she starts with the conditions in which is arises:

[W]e view fascism as an expression of the decay and disintegration of the capitalist economy and as a symptom of the bourgeois state’s dissolution. We can combat fascism only if we grasp that it rouses and sweeps along broad social masses who have lost the earlier security of their existence and with it, often, their belief in social order.

Fascism attempts to have a mass appeal, but tries in particular to appeal to middle class layers that face declining living standards and increased insecurity — those “experiencing the collapse in the hopes that they had placed in the war,” as Zetkin wrote about the Italian example.

But fascism attempts to recruit from other social classes. Zetkin argues that fascism “became an asylum for all the politically homeless, the socially uprooted, the destitute and disillusioned. And what they no longer hoped for from the revolutionary proletarian class and from socialism, they now hoped would be achieved by the most able, strong, determined and bold elements of every social class.”

Following the crushing of the workers’ revolution, fascism now attempted to appeal to this broader layer, which might have felt compelled to side with the workers’ struggle at its height.

To make this appeal, fascism may also put up an anti-capitalist veneer. So, for instance, Mussolini claimed that he wanted to improve the lives of workers and supported women’s rights, the eight-hour day and raising the minimum wage. He claimed to want to create “fascist trade unions.” Once in power, Mussolini didn’t make good on these demands.

In order bind all these sections of society together, fascism promotes national chauvinism and strength in national unity, thus also promoting war and militarism.

Zetkin also describes the importance of the violent terror of the fascists — the key role that fascist gangs in the streets played in whipping up fear, and attacking trade unions and others, all in order to put a stop to any independent working-class fightback.

At a certain point, she argues, sections of the capitalist class see no other alternative to the threat of workers taking power than to support and finance the fascists — as they recognize that the bourgeois state doesn’t have the power to push workers back or to lead:

The bourgeoisie can no longer rely on its state’s regular means of force to secure its class rule. For that it needs an extralegal and non-state instrument of force. That has been offered by the motley assemblage that makes up the fascist mob. That is why the bourgeoisie offers its hand for fascism’s kiss, granting it complete freedom of action, contrary to all its written and unwritten laws. It goes further. It nourishes fascism, maintains it, and promotes its development with all the means at its disposal in terms of political power in and hordes of money.

***

Taken altogether, Zetkin’s analysis offered something completely different than other views at the time — and today for that matter. And she had developed, as early as 1923, a serious understanding of this new phenomenon that many reformist social democrats failed to take seriously.

The first step was understanding the nature of this unique threat to the working class. Along with that came a unique method for fighting back against the fascist menace: the united front. While other revolutionaries, namely Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky, would expand and shape the idea of the united front against fascism in the 1930s, Zetkin argued for it in 1923.

Haymarket’s edition of Fighting Fascism also includes important documents that illustrate how Zetkin tried to bring her analysis and call to action to the international communist movement, including the 1923 resolution she proposed to the executive committee of the Communist International and documents from a Frankfurt conference against fascism.

Central to her understanding of destroying fascism was that the working class had to organize to defend itself and its organizations, including armed self-defense units. She wrote:

At present the proletariat has an urgent need for self-defense against fascism, and this self-protection against fascist terror must not be neglected for a single moment. At stake is the proletarians’ personal safety and very existence, as well as the survival of their organizations.

Self-defense of proletarians is the need of the hour. We must not combat fascism in the way of the reformists in Italy, who beseeched them to “leave me alone, and then I’ll leave you alone.” On the contrary! Meet violence with violence. But not violence in the form of individual terror — that will surely fail. But rather violence as the power of the revolutionary organized proletarian class struggle.

In order to defeat fascism, Zetkin argued, it cannot be ignored, but must be opposed by a broad layer of working-class organizations, including those with different political views, which may not agree with socialism, coming together to defeat it. She wrote:

Fascism does not ask if the worker in the factory has a soul painted in the white and blue colors of Bavaria; the black, red and gold colors of the bourgeois republic; or the red banner with the hammer and sickle. It does not ask whether the worker wants to restore the Wittelsbach dynasty [of Bavaria], is an enthusiastic fan of [SPD leader and German President Friedrich] Ebert, or would prefer to see our friend [CP leader Heinrich] Brandler as president of the German Soviet Republic.

All that matters to fascism is that they encounter a class-conscious proletarian, and then they club him to the ground. That is why workers must come together for struggle without distinctions of party or trade union affiliation.

Hand in hand with these arguments about defeating the fascists, Zetkin insisted on the need for a complete transformation of capitalist society. The workers have the power to defeat fascism, she wrote, and in that process, the contradictions of capitalism are laid to bare, and the necessity of revolution is shown.

Zetkin’s emphasis on an international struggle and the importance of workers’ and socialist organizations around the world taking up this fight is key — and should inform those today trying to understand the rise of right around the world.

As she points out, fascism may take different forms depending on the country where it is organizing, and it must be identified in each of its horrific iterations. But an understanding of fascism’s character and how to defeat it has to be shared by the entire international working class.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. We have hours left to raise the $12,0000 still needed to ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.