The Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP) is a 303-mile, 42-inch diameter fracked gas pipeline that, if completed, will stretch from northwestern West Virginia through southern Virginia. It will have three compressor stations along its route, all in West Virginia, and an attached 31-mile pipeline, MVP Southgate, that will expand the transport of fracked gas into North Carolina.

The MVP was proposed in 2014, but it has faced intense opposition from landowners, Indigenous communities, and climate advocates, who say the pipeline’s polluting impacts will be the equivalent of 23 new coal-fired power plants. Concerted legal challenges and direct action protests have stalled the pipeline’s construction, and its estimated costs have boomed from an initial $3.5 billion nearly a decade ago to $7.2 billion today.

The owners of the MVP received a major gift when President Joe Biden struck a deal with West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin, a true fossil fuel loyalist, to quicken the approval of the MVP as part of the June 2023 debt agreement. As an interstate pipeline, the MVP will be regulated by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) but will also need permits from other federal and state agencies.

Today, MVP owners claim the pipeline is 94% constructed and will be operational in the fall of 2024, though pipeline opponents say this is untrue, even according to the company’s own reports. MVP owners have increasingly coordinated with “fusion centers” and local police to increase repression of protesters in the forms of arrests, fines, lawsuits, and harsh new state laws.

Behind the MVP exists a wider power structure composed of CEOs, board directors, asset managers, and big banks who all stand to profit from the pipeline, and indeed already have. The names of consumer-facing financial firms like Bank of America, Wells Fargo, JPMorgan Chase, BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street are all propping up and profiting from the MVP even as they give lip service to issues like “sustainability” and “net-zero commitments.”

Even more, the main owner and operator of the MVP, Equitrans Midstream, is now being acquired by EQT Corporation, one of the top fracking corporations in the U.S. Executives from both Equitrans and EQT donated big to Joe Manchin as he extracted approval of the MVP. And some of the top regulators of the pipeline — including the chairman of FERC and the heads of crucial state environmental agencies — have alarming ties to the fossil fuel industry.

This post highlights six important things that organizers taking on the MVP should know.

1. There’s new MVP ownership coming

The driving force behind the MVP over the past several years has been its top owner and sole operator, Equitrans Midstream. The MVP’s website lists Equitrans (the parent company of EQM Midstream Partners) as having a “45.5% significant ownership interest” in the MVP. Media reports have also put Equitrans’ stake at 48.1%.

After Equitrans, other parties to the MVP joint venture are NextEra Energy (31% ownership interest; Con Edison Transmission (12.5% interest); WGL Midstream (10% interest); and RGC Midstream (1% interest).

But in early March 2024, EQT Corp, the top fracking company in the Marcellus Shale region, announced that it was acquiring Equitrans in a $14 billion all-stock deal. Equitrans was previously part of EQT Corp but spun off in 2018 into an independent company. EQT Corp played a leading role in driving the fracking boom in the Marcellus Shale region, especially in Western Pennsylvania, where they’re headquartered, in the 2000s and 2010s. The company grew bigger in 2017 when it acquired Rice Energy, and current EQT Corp president and CEO Toby Z. Rice — who says the MVP will unleash an “AI power boom” — was a top executive with Rice Energy before the acquisition.

The significance of this merger (following its likely approval in the fall) for the MVP is that it will soon have a new owner: EQT Corp. In acquiring Equitrans, EQT Corp is joining a wave of massive fossil fuel mergers that are evermore consolidating the industry into the hands of a few big players. Following the merger, which is contingent on FERC approval of the MVP beginning service, EQT Corp says it will be worth around $35 billion.

2. MVP CEOs rake in tens of millions — including a $7.5 million bonus specifically tied to the MVP — while board directors have powerful Big Oil ties

Thomas F. Karam is the chairman of current MVP top owner Equitrans, and until January 2024 he also served as company CEO. In January 2024, Diana M. Charletta was appointed the new CEO of Equitrans.

From 2021 to 2023, Karam took in $39,245,673 in total CEO compensation, with over half in stock awards. As part of that compensation, Karam received a whopping $7.5 million cash bonus in 2023 “in express recognition of his relentless efforts towards navigating legal and regulatory setbacks to the MVP project,” particularly working with Congress and the Biden administration to win the “legislative achievement” of the inclusion of the MVP in the 2023 Fiscal Responsibility Act.

The next biggest owner of MVP after Equitrans is the energy company NextEra, whose CEO, John W. Ketchum, took in $40,440,264 from 2020 to 2022.

With MVP ownership switching to EQT Corp, the new top pipeline executive will be EQT Corp CEO Toby Z. Rice, who took in $39,121,426 in total compensation from 2021 to 2023.

In becoming the new owners of the MVP, Rice and EQT Corp will be governed by a board of directors that is firmly dedicated — despite verbiage around “clean-burning” natural gas — to the extracting and burning of dirty fossil fuels, with several directors tied to some of the most powerful and polluting corporate actors in the industry. Board chair Lydia I. Beebe is the former Corporate Secretary and Chief Governance Officer of Chevron; Janet L. Carrig is the former Senior Vice President, General Counsel and Corporate Secretary of ConocoPhillips; Anita M. Powers is the former Executive Vice President of Worldwide Exploration for Occidental Oil and Gas Corporation and Vice President of Occidental Petroleum, as well as a former director of California Resources Corporation; and James T. McManus II is the former Chairman, Chief Executive Officer and President of Energen Corporation, a huge Permian Basin driller, acquired by Diamondback Energy in 2018.

As LittleSis has previously noted, longtime former EQT Corp CEO, President and Chairman Murry Gerber raked in tens of millions of dollars as he oversaw the company from 1998 to 2011 while it drove the fracking boom. Gerber has served on the board of directors of asset management giant BlackRock since 2000, and as its Lead Independent Director since 2017. BlackRock is a 7.89% beneficial owner of EQT Corp (see below).

3. MVP owners donated big to Joe Manchin before and after he won approval for the pipeline from the Biden administration

Joe Manchin played a pivotal role in winning federal backing of the MVP when he made his approval — and deciding Senate vote – of President Joe Biden’s June 2023 debt deal contingent on Biden and the debt legislation accelerating the approval of the MVP

According to campaign finance filings, in the lead-up and shortly after that agreement, just five Equitrans Midstream employees donated a combined $25,800 to Joe Manchin, from 2021 to late 2023, including $10,000 from current CEO Diana Charletta. EQT Corp CEO Toby Rice also donated $8,100 to Joe Manchin from 2021 to 2023.

4. BlackRock, Vanguard, State Street and other asset manager are major owners of companies that own and operate the MVP

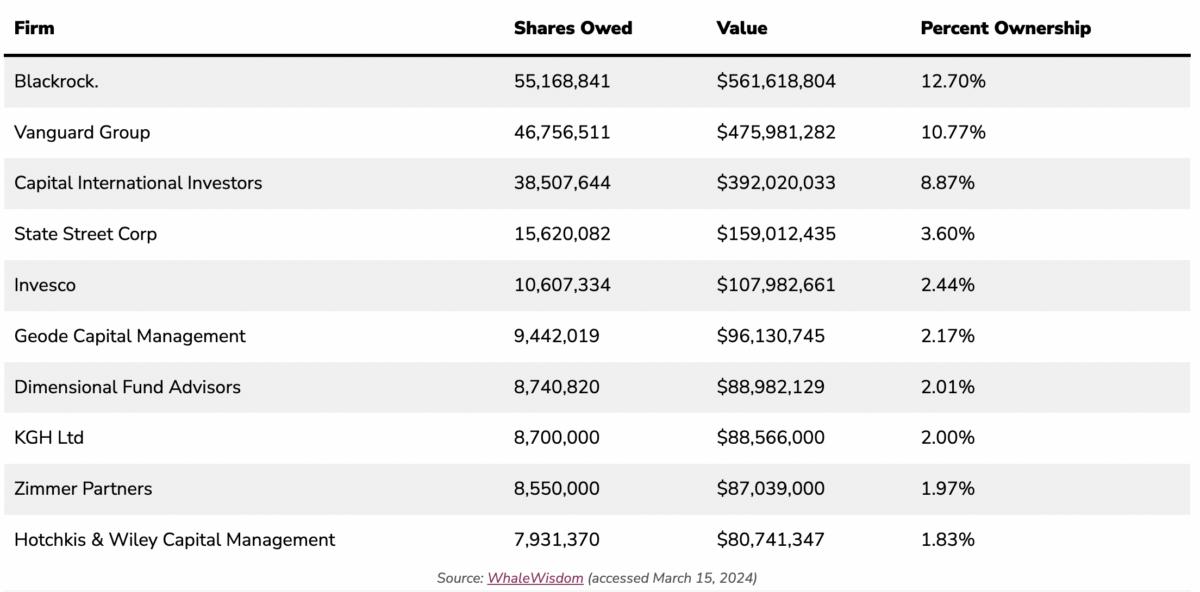

The table below shows the ten largest shareholders of Equitrans Midstream, the current top stakeholder and operator of the MVP.

According to Equitrans’s 2024 proxy statement, it also has three top beneficial owners of Series A Preferred Stock (which are shares that have priority when the company pays out dividends): CIBC Private Wealth Group, D.E. Shaw Galvanic Portfolios, and NB Burlington Aggregator.

The table below shows the ten largest shareholders of EQT Corp, which is set to become the top stakeholder and operator of the MVP once its acquisition of Equitrans is completed. The top shareholder is T. Rowe Price, one of the world’s largest asset managers with $1.35 trillion under assets, followed by Vanguard, BlackRock, and State Street.

BlackRock, Vanguard, State Street, Capital Group and Invesco are top ten shareholders of both Equitrains and EQT Corp. BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street are among the top four beneficial owners of both companies. In addition to being the top shareholder of EQT Corp, T. Rowe Price is also the 15th top shareholder of Equitrans.

Based on this data, the map below shows the top shareholders of both current MVP top owner and operator Equitrans and near-future MVP top owner and operator EQT Corp.

5. Wells Fargo, Bank of America and other consumer-facing banks are propping up the MVP

A number of banks provide Equitrans and EQT Corp with financing, in the form of credit facilities and term loans, that they can draw on to fund the MVP. These include prominent consumer-facing U.S. banks, such as Bank of America, Wells Fargo and JPMorgan Chase. While these banks are not providing financing specifically for the MVP, they provide general funding that the pipeline owners can use for business operations for the MVP.

Previous reports, such as 2017 and 2020 reports by Oil Change International, have documented the billions in credit agreements, senior notes, and unsecured loans that 25 banks have provided MVP’s owners.

Many of the same banks continue to finance current MVP owner Equitrans. According to an April 2022 reinstated credit agreement filing, the 21 banks providing a $2.16 billion credit facility include:

Wells Fargo serves as the “Administrative Agent, Swing Line Lender and L/C Issuer” in this credit facility, meaning that it oversees and facilitates the day-to-day operations of the credit agreement with Equitrans, including in providing short-term loans.

Wells Fargo also oversees Equitrans issuing and selling of bonds to raise capital for the company’s business operations. For example, in February 2024, Equitrans filed a purchase agreement of $600,000,000 in senior notes led by Wells Fargo, with Bank of America, Citigroup, JPMorgan Chase, PNC bank and others initially purchasing tens of millions each in Equitrans bonds.

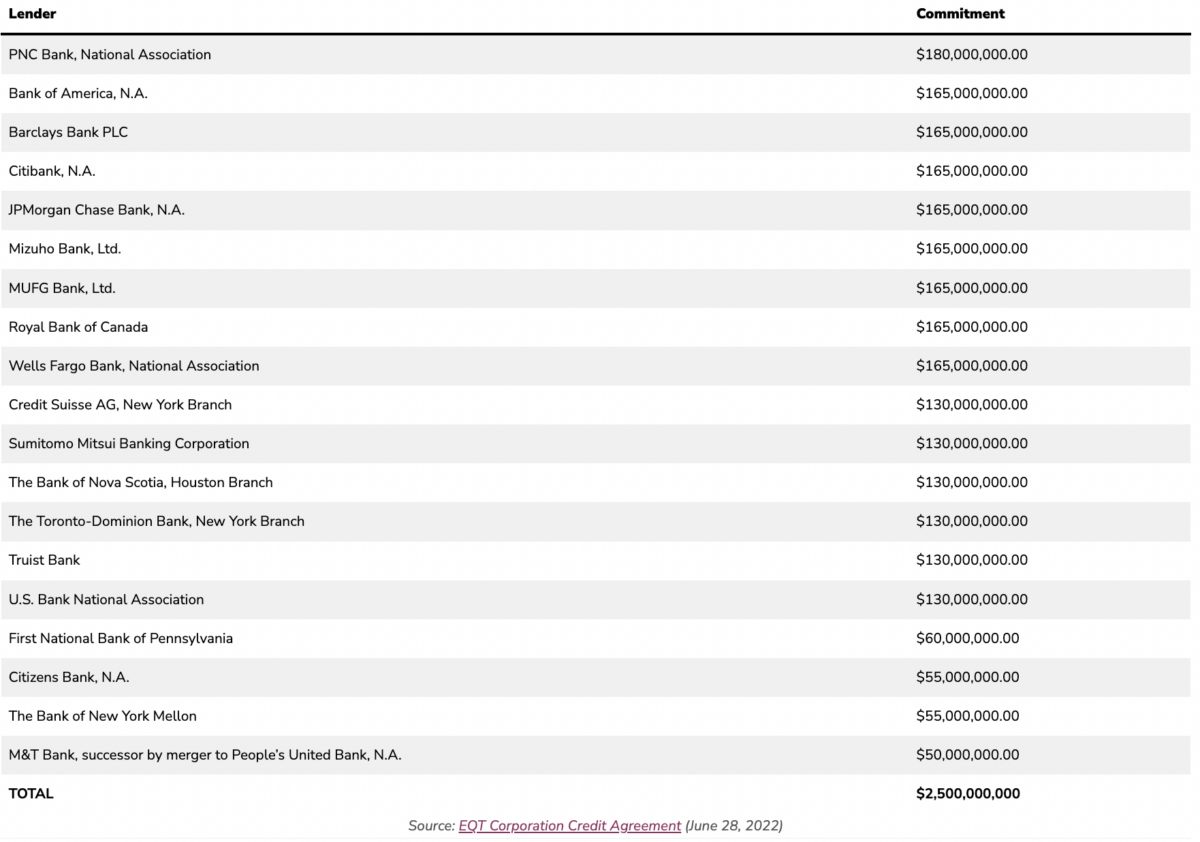

While these banks have been financing Equitrans, they will continue to finance the main company behind the MVP even as its ownership changes to EQT Corp. For example, EQT Corp disclosed a $2.5 billion credit facility (referenced in their most recent 10-K annual report) in June 2022 whose Administrative Agent is PNC Bank and which also includes Bank of America, Wells Fargo, Citibank, JPMorgan Chase, and others as lenders:

In January 2024, EQT Corp announced an amended credit agreement for $750,000,000. EQT Corp is financed by these banks in other ways: for example, a September 2022 agreement to issue and sell $1 billion in senior notes with maturity dates of 2025 and 2028.

In financing the companies behind the MVP, these banks face substantial financial and reputational risks. The MVP has faced constant delays, with its costs booming. Equitrans 2024 outlook was downgraded by an analysis in early March because of “a confluence of challenges” that include “operational delays and financial headwinds.” Upon EQT Corp’s announcement of its acquisition of Equitrans, Reuters reported that investors were “unimpressed” by EQT’s debt levels, and its share price dropped by 8%.

Moreover, the MVP is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to bank financing of fossil fuels and environmental injustice. From 2016 to 2022, Bank of America has provided $279.73 billion in financing to the fossil fuel industry, Wells Fargo has provided $316.7 billion, and JPMorgan Chase has provided $434.154 billion, according to the latest “Banking on Climate Chaos” report.

6. Key pipeline regulators have ties to the oil and gas industry, including the MVP itself

Key regulatory agencies, from the federal to the state levels, are led by regulators who have immediate past ties to the oil, gas and utility industries.

Most egregiously, a March 2024 investigation by the Roanoke Times found that Michael Rolband, who has served as Director of Virginia’s Department of Environmental Quality since 2022, formerly ran a consulting firm, Wetland Studies and Solutions Inc., that was hired by the Mountain Valley Pipeline to “provide advice on dealing with the impacts of running a 42-inch diameter natural gas pipeline through streams and wetlands.” The investigation said that in the past Rolband had been “paid an hourly rate” by MVP for his consulting.

The VA DEQ is one of the key state regulatory agencies overseeing the MVP, which partially runs through Virginia. According to the investigation, at the time Rolband was appointed as Director of the VA DEQ, the agency “had cited Mountain Valley with more than 300 violations of erosion and sediment control regulations during construction” and fined the company $2.15 million in 2019 as part of a consent decree to crack down on future violations. But from the summer of 2023 to March 2024, under Rolband’s authority, Mountain Valley “has so far been cited for just two violations of the consent decree and fined $2,500,” according to the investigation.

Currently, Mountain Valley Pipeline is also proposing MVP Southgate, a 31-mile addition to the MVP that would run from Virginia into North Carolina. While it needs FERC approval as an interstate pipeline, MVP Southgate would also be regulated by the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality.

Elizabeth Biser has headed the North Carolina agency since 2021. While Biser lists seeming environmental bona fides like previously serving as Vice President of Policy and Public Affairs of the Recycling Partnership, these ties raise questions about her closeness to the fossil fuel industry.

The Recycling Partnership is an industry-backed group that is funded by major corporations and organizations with a vested interest in fossil fuel and fossil fuel-based plastics production, including ExxonMobil, the American Chemistry Council, and dozens of companies that depend on single-use plastics wrapping.

During 2020 and 2021, Biser served as one of their chief lobbyists, lobbying for the Recycling Partnership both through her own firm, Biser Strategies, and as an in-house lobbyist for the Recycling Partnership.

During that time, lobbying efforts that Biser was involved in, either solely or as a team, reported $650,000 in expenses. The filings were typically vague about issues lobbied on, such as “[m]atters related to recycling programs and the circular economy that involve policies and proposals affecting federal, state and local recycling initiatives.”

In 2017, Biser also submitted lobbying filings in North Carolina for United Oil of the Carolinas, which supplies fuel from BP, Shell, Marathon, ExxonMobil, and others, though it’s unclear if she did any actual lobbying. In North Carolina in 2017 and 2018, she also lobbied for Blue Gas Marine, Inc., which describes itself as “a leader in the marine industry, pioneering natural gas fueling solutions for boaters around the world.”

Perhaps most alarming, Willie L. Phillips, the chairman of FERC, the key federal body agency regulating the MVP, has longtime and extensive ties to the fossil fuel industry. Biden’s appointment of Phillips to chair FERC, which must approve the MVP, was strongly opposed by hundreds of climate groups.

The American Prospect has documented Phillips’ coziness with utilities and oil and gas companies as an attorney and regulator. Phillips previously worked at two law firms, Van Ness Feldman and Balch & Bingham, where he represented clients in the energy industry, including fossil fuel utility giant Southern Company.

As chair of the District of Columbia’s Public Service Commission (DCPSC), Phillips “show[ed] extreme loyalty” to utilities Pepco and Washington Gas, and he voted in favor of Exelon’s takeover of Pepco, deepening monopoly consolidation of the utility industry and “disincentiviz[ing] Pepco from greening their electric services, because other Exelon-owned companies rely on fossil energy for their profits—not to mention that Exelon has historically fought to kill wind and solar subsidies in favor of dirty energy.”

Phillips also served alongside fossil fuel field services and utility representatives on the Keystone Policy Energy Center board and the Electric Power Research Institute Advisory Council.

While Biden’s debt deal was a boost to the MVP, its completion and operation is not guaranteed. Opponents have succeeded in stalling and delaying the pipeline for years, and the financial solvency and political fate of new fossil fuel infrastructure projects can swing wildly. As community members, landowners, and climate advocates continue to try to halt the pipeline, it’ll help to follow the money and understand the financing and networks behind the pipeline’s owners — both old and new.