Honest, paywall-free news is rare. Please support our boldly independent journalism with a donation of any size.

Nogales, Mexico – Sixteen-year-old Jose Antonio Elena got the kind of punishment that those who toss rocks at Border Patrol agents receive with startling frequency: He was shot with a .40-caliber round from an agent’s service weapon.

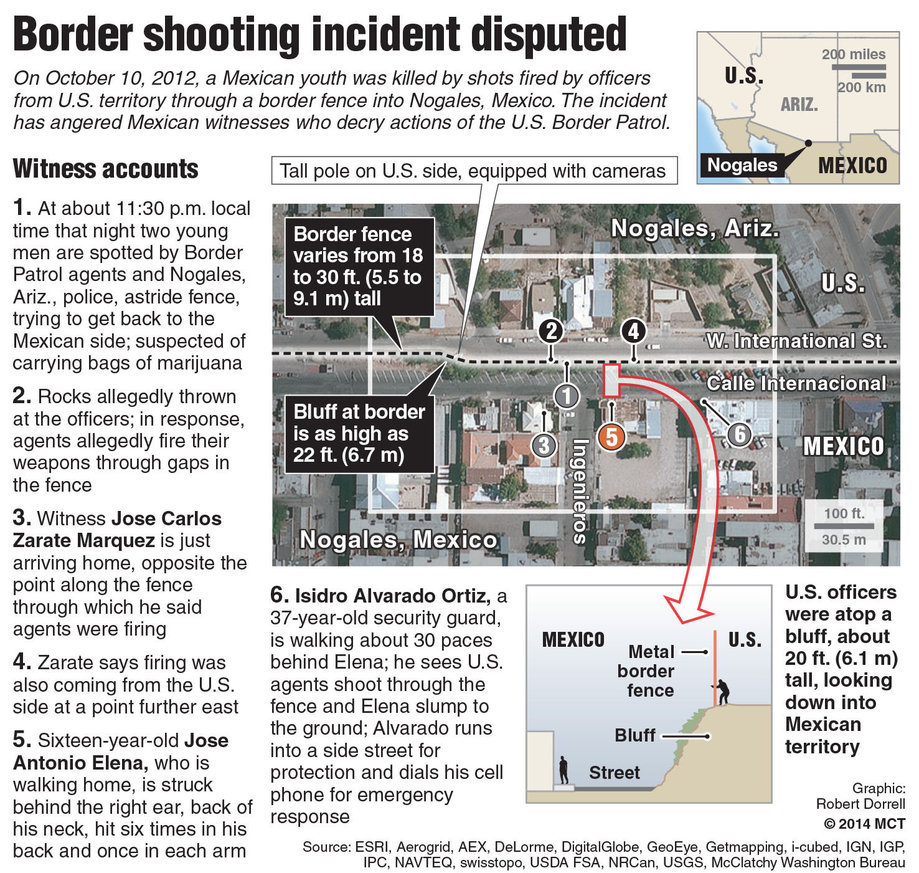

The bullet hit Elena in the back of the head. He slumped mortally wounded to a sidewalk on the Mexican side, a few paces from the border fence. At least two agents, perched on the U.S. side about 20 feet above the street and shielded by the fence’s closely spaced iron bars, continued to fire, witnesses said. In all, 10 bullets struck Elena, spattering a wall behind him with blood.

Yet Jose Antonio Elena may not have tossed any rocks at all. He may have been just walking on a sidewalk on Mexican soil, an innocent passerby.

The Border Patrol has a video of the events that night, Oct. 10, 2012. The video likely shows whether U.S. agents killed an innocent Mexican or shot a member of a marijuana smuggling ring. But the U.S.’s largest law enforcement agency refuses to make the video public. The agents remain on the job, neither publicly identified nor receiving any disciplinary action.

Elena’s killing is one in a string of what critics say are unnecessary killings by Border Patrol agents along the U.S. border with Mexico. At least 21 people have died in confrontations with Border Patrol agents, often out of sight of witnesses or fellow agents, in the past four years.

Those cases include 10 people who’ve been killed for throwing rocks, according to the Border Patrol’s own statistics, and there have been 43 cases since 2010 when agents have opened fire on rock throwers. But there are no known cases where an agent has been disciplined for improperly using force.

Border Patrol chief Michael J. Fisher defended his agents earlier this month, saying they had shown remarkable restraint and pointing out that they’d been pelted with rocks 1,713 times in the same period. Still, he issued a directive telling his agents to take cover, rather than open fire, when items are thrown their way. He added, however, that rocks can be deadly projectiles, and agents may shoot when their lives are in danger.

The Border Patrol did not respond to requests for information about Elena’s death. At the time of the shooting, it issued a statement saying that a lone agent had “discharged his service firearm” after suspected smugglers ignored “verbal commands from agents” to stop throwing rocks, according to an Oct. 13, 2012, story posted on the website of the local newspaper, the Nogales International.

The Border Patrol acknowledged then that surveillance cameras had captured the event and that the video had been turned over to the FBI.

A spokesman for the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Arizona, Cosme Lopez, said he could “neither confirm nor deny” any information about the Elena killing, including whether an investigation was still open.

Critics are skeptical, however, about the Border Patrol’s version. They note that in Elena’s case, witnesses say that at least two agents fired, that both were well above whoever might have been throwing rocks, and that they literally stretched their arms across the border to shoot.

The agents fired between 25 and 30 rounds from their overlook, witnesses said _ some apparently wildly, despite the scene being a busy downtown area. Pock marks can still be seen high on the wall of a nearby residence.

One witness on the Mexican side of the border calls Elena’s death murder. Those tossing rocks ran down a side street, escaping before the shooting started, he said. Elena was walking on the sidewalk when the rock throwers darted past him.

“To me, it was cold-blooded murder,” said Isidro Alvarado Ortiz, a 37-year-old security guard who said he was walking about 30 paces behind Elena when the agents opened fire.

Alvarado has given testimony to the FBI but like several Mexicans involved in the case, he has grown frustrated at the lack of U.S. action on the investigation.

“Imagine if it had occurred the other way around – if a Mexican had killed one of them. They would’ve come the next day to get the person,” Alvarado said.

Tony Estrada, the sheriff of Arizona’s Santa Cruz County, where the U.S. half of Nogales is located, calls the apparent limbo into which the case has fallen after 18 months a “failure.”

“I’ve been in law enforcement for 46 years, and I’ve never seen an agency shoot at anybody because they had a rock thrown at them,” he said. “It needs to be aired out. If there’s responsibility, we need to place that responsibility.”

No one disputes that young unarmed smugglers carrying drugs scamper over the border fence every day of the week, using spotters to warn of the movements of Border Patrol vehicles and rock throwers to divert attention.

One has to see the fence climbing to believe how common an occurrence it has become. The fence is 18- to 30-feet tall – a seemingly impassable barrier.

But at midafternoon on a recent weekday, a reporter was speaking to a bus line employee near the fence when the employee nodded in an opposing direction. Two youths loped across the road a block away and shimmied up the interconnected steel tubes that comprise the fence, hoisting their bodies over the top and sliding down the other side – all within 30 seconds. Several minutes later, and just as quickly, they climbed back over the fence into Mexico.

The night of Elena’s killing, Nogales, Ariz., police officers and Border Patrol agents were summoned around 11:30 p.m. to snare fence climbers carrying what was assumed to be bundles of marijuana.

Among them was municipal K-9 officer John V. Zuniga, who arrived to see two young men scaling the fence to get back into Mexico. On the Mexican side, fellow Mexicans yelled profanities at the law enforcement agents.

“I then heard several rocks start hitting the ground and I looked up and I could see the rocks flying through the air. I advised communications that we were being rocked and I advised the other units to stay clear,” Zuniga later wrote in a police report.

A fellow agent said, “Hey, your canine’s been hit!” the report said.

As he took cover, Zuniga wrote, he heard “several gunshots go off and I saw an agent standing near the fence. I advised communications that gunshots were being fired, and I was unsure where the gunshots were coming from and who was firing them.”

On the other side of the border, Jose Carlos Zarate Marquez, a local Mexican restaurateur, was just pulling into his driveway at the corner of Internacional Street _ which runs parallel to the border fence – and Ingenieros Street when he heard a commotion. Zarate peeked from the edge of his property.

Two young Mexican males were near the top of the fence on the U.S. side. Border Patrol agents were trying to get them to come down.

“They were poking at them with a stick,” Zarate said.

Four youths on the Mexican side tried to distract the Border Patrol.

“They threw rocks to shoo away the agents and to let their companions through,” Zarate said, adding that the two Mexicans made it over the fence and all six began scattering across the street.

It was then that shots rang out.

“There were about 30 shots – from the two sides. Up there and over there,” Zarate said, pointing to the top of a knoll and a lower spot to the east.

“They were shooting helter-skelter. Look at all the pockmarks on that building,” he said, pointing to a building on a corner opposite his house that is the office-residence of a local physician.

The victim of the night’s gunfire, Jose Antonio Elena, was a 5-foot-9 teenager who dreamed of a life in the military.

“He’d say, ‘As soon as I turn 18, I am joining the army,’” recalled his mother, Araceli Rodriguez, a 41-year-old bank worker, as she sat in her home near an impromptu altar centered on a large framed photo of the adolescent. The home is about a quarter of a mile from where he was killed.

The night of the killing, Rodriguez said, her son left home to meet his older brother, Diego, who was finishing his shift as a clerk at a local convenience store. When Jose Antonio got to the store, colleagues said Diego had already left.

Jose Antonio strolled back along Calle Internacional, the well-illuminated street that hugs the high steel border fence that divides Nogales in half and separates the two countries.

Today, wall posters that declare, “We demand justice, Jose Antonio Elena Rodriguez,” as well as a metal cross bearing an image of the slain youth mark the spot where the teenager was hit with the first bullet behind his right ear. Other bullets came fast: one to the back of the neck, six in the back and one in each arm, according to the autopsy report.

Crime scene photos show Elena wearing a bloodstained short-sleeve gray shirt, jeans, checked boxer shorts and gray-and-black sneakers. None of that clothing matches what Officer Zuniga said he saw on the two fence jumpers whose escape to Mexico had started the melee. One wore a white shirt, the other a blue one, Zuniga wrote in his report.

Overhead – at the top of the knoll on the U.S. side of the border – is a metal pole topped with remotely operated video cameras that monitor the border. There is little doubt that one of the cameras captured the scene, including whether any rock thrower wore clothing matching what was found on Elena.

What appears on that video “is huge. It’s very important. It will verify whether the civilian witnesses are being truthful about what occurred that evening,” said Luis F. Parra, an American attorney for Elena’s family who has filed a notice of claim against the U.S. government for wrongful death.

“If it showed him throwing rocks, they would have exhibited it already,” added the family’s Mexican attorney, Manuel Iniguez Lopez.

Reticence by the Border Patrol to release the video is understandable. Errors in judgment would be embarrassing to agents and potentially costly to taxpayers.

Another Border Patrol agent, Nicholas Corbett, faced two second-degree murder trials after allegedly shooting a migrant dead in January 2007. Both trials ended in hung juries, but press reports from the time say the U.S. government paid $850,000 in civil remedies to surviving family members.

A video might also show whether Border Patrol agents were in “imminent danger of death or serious injury” from thrown rocks, a precondition for using lethal force.

“You’d have to be a Major League pitcher to hurt someone,” Iniguez said, noting that the height of the hill and the towering nature of the fence itself offered the agents protection. “We want to see photos of the damage those rocks did to windows and to the agents.”

In the only other fatal shooting of a rock thrower in Nogales in recent years, video played a key role in quieting disgruntlement in Mexico.

That case also involved a minor, Ramses Barron Torres, a 17-year-old, who around 3 a.m. on Jan. 5, 2011, was among an alleged group of smugglers on the eastern outskirts of Nogales that was thwarted by Border Patrol agents as they crossed into the United States.

According to a report dated Aug. 8, 2013, from the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice, the group scuttled back over the wall with their marijuana loads and began tossing rocks.

“A videotape of the incident shows the victim hurling rocks into the U.S. from the Mexico side of the fence, then falling to the ground suddenly while he was in the midst of throwing a rock,” the report says.

Like in the Elena case, agents fired through the slits in the fence and shot Barron Torres while he was on Mexican soil.

Curiously, by waiting for the smugglers to get back into Mexico and shooting them there, the agents sidestepped a possible crime. “A civil rights crime does not exist because the victim was in Mexico when he was shot and killed,” the report says, adding that it was impossible to disprove that the agent was acting in self-defense.

Still, Mexican officials said U.S. law enforcement should find means to disable rock throwers other than lethal force. Some say it doesn’t matter if Elena tossed a rock or not.

“International treaties say you can’t shoot another person if they are unarmed,” said Hector Quintero Pacheco, the Sonora state human rights ombudsman in Nogales.

It is an opinion that is widespread in Nogales.

“He was just a kid. I don’t think it is fair to take someone’s life just for a rock,” said Samuel Santos, an 18-year-old who works in a call center and speaks native English.

“People keep asking me, ‘What was your son doing there?’ But no one answers my questions,” Elena’s mother said, and a torrent of questions poured from her lips.

“Who are the killers and why haven’t they been tried? Who are they to avoid justice?” she asked. “Can we Mexicans stick our arms through the border fence and start to shoot?”

A terrifying moment. We appeal for your support.

In the last weeks, we have witnessed an authoritarian assault on communities in Minnesota and across the nation.

The need for truthful, grassroots reporting is urgent at this cataclysmic historical moment. Yet, Trump-aligned billionaires and other allies have taken over many legacy media outlets — the culmination of a decades-long campaign to place control of the narrative into the hands of the political right.

We refuse to let Trump’s blatant propaganda machine go unchecked. Untethered to corporate ownership or advertisers, Truthout remains fearless in our reporting and our determination to use journalism as a tool for justice.

But we need your help just to fund our basic expenses. Over 80 percent of Truthout’s funding comes from small individual donations from our community of readers, and over a third of our total budget is supported by recurring monthly donors.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser to add 340 new monthly donors in the next 5 days. Whether you can make a small monthly donation or a larger one-time gift, Truthout only works with your support.