Support justice-driven, accurate and transparent news — make a quick donation to Truthout today!

“Brian was a regular kid,” longtime communications professional Kathy Parrent says, “a boy who liked to make everyone in our third grade classroom laugh. One day he said something smart-alecky, and our teacher grabbed him by the collar, lifted him up, opened up the coat closet, threw him in and locked the door. The rest of us sat in stunned horror, terrified. Brian immediately began banging and screaming, ‘please, please, let me out,’ but the teacher kept him in there for what felt like an eternity.”

As Parrent speaks, her voice breaks and it is clear that Brian is still vivid in her mind’s eye. “I remember that he was wearing a white shirt and when the teacher finally opened the door, he was covered in blood. My first thought was that he must have cut himself, but no. He’d had a nosebleed, something that happened to him all the time. It was awful. He might have deserved to be reprimanded; I don’t know. What I do know is that more than 50 years later, I can still see the blood.”

Despite the lasting impact of this incident on Parrent — we can only guess how it affected Brian as he continued his schooling and came of age — it’s tempting to assume that this type of discipline is a thing of the past. After all, the encounter took place in 1963.

Security officers routinely use mace, pepper spray, stun guns and Tasers to break up fights and suppress “unruly” behavior.

But not only are students still being locked in “isolation rooms” and physically restrained, but 19 states also continue to employ corporal punishment against “disobedient” pupils. What’s more, in the wake of Columbine, Sandy Hook and other school shootings, security officers — often employees of the local sheriff’s department or area police force — routinely use mace, pepper spray, stun guns and Tasers to break up fights and suppress “unruly” behavior.

First, let’s look at corporal punishment. Since there are no federal policies regarding the paddling or physical punishment of students, a patchwork of state regulations govern how students can be disciplined. This means that although 31 states prohibit public school teachers, paraprofessionals and principals from striking students — only two states, Iowa and New Jersey, ban private schools from doing the same. The practice remains pervasive, particularly in the South.

To wit: Available statistics show Texas leading the nation, with 49,197 students being paddled at least once during the 2008-09 academic year; Mississippi came in second, with 38,131 cases; then there’s Alabama, with 33,716; Arkansas, with 22,314; Georgia, with 18,249; Tennessee with 14,868; and Oklahoma with 14,828.

Children with disabilities are between two and five times more likely to be hit than other students.

For those unfamiliar with this type of chastisement, it is worth noting that the paddle is typically made of wood and is used on the thighs and buttocks for infractions such as bullying, “defiance,” fighting, using profanity, refusing to put a cell phone away, smoking on school grounds, tardiness or violating a school dress code.

Equally noteworthy, boys of color receive the stick far more frequently than white males or females, regardless of race. Indeed, more than a third of those paddled during that school year — 35.6 percent — were Black boys.

The 12 to 15 percent of public school students living with disabilities also experience disproportionate corporal punishment, regardless of race and regardless of whether they have learning disorders, are autistic or have illnesses ranging from cerebral palsy to asthma. According to the Gundersen National Child Protection Training Center, children with disabilities are between two and five times more likely to be hit than other students.

And paddling, of course, is only one of the tools used to control them.

Isolation or Seclusion for Students With Disabilities

Historically, time-outs, also known as seclusion or isolation, have been used to give students a means of stepping away from stimuli. “People typically couch removal from class in therapeutic language, but there is no research to back up the use of isolation as helpful,” said Gail Stewart, an attorney in Albuquerque, New Mexico, who has represented numerous children with disabilities in lawsuits against punishment-happy school systems. “What isolation teaches is trauma.”

New Mexico, she adds, like most other states, does not require parents to be notified when their children are put in seclusion or are restrained, and since many of those placed in involuntary isolation are nonverbal, family members are often unaware of what’s happening in the classroom. “Many kids become highly distressed when sequestered,” Stewart told Truthout. “You can see blood and snot, and smell urine, in these holding rooms. “

“No one has solid numbers on the number of officers with Tasers or sprays, how much is spent by school districts, or exactly where they are used.”

She described a typical scenario, illustrating the type of provocation that can send a student into seclusion. “A kid who does not want to transition from one activity to another may throw a book or push a desk,” she said. “The teacher then calls security. In some cases, the room will be cleared of other students, leaving three or four adults to surround the kid who is considered ‘noncompliant.’ If the kid ends up on the floor, it can escalate into head-banging or thrashing, and may result in injuries.”

In addition, says Matthew Bernstein, staff attorney at Albuquerque’s Pegasus Legal Services for Children, “zero-tolerance” policies in some schools complicate things further by prohibiting teachers from using discretion when handling disruptive behaviors. “I was a high school teacher before I went to law school,” he said. “I know it’s hard to be a teacher and individualize what each student needs, but it’s time to dial back the punishments and find alternatives.”

This is especially true when punishment includes being tased, zapped with a stun gun or sprayed with chemicals.

That said, no one knows how often, or even where, these methods are used.

“There is not a federal mandatory school crime [sic] incident reporting system for Pre-K though 12 grade school crime,” Ken S. Trump, president of National School Safety and Security Services, wrote in response to an email from Truthout requesting hard data. “No one has solid numbers on the number of officers with Tasers or sprays, how much is spent by school districts, or exactly where they are used,” he wrote.

Instead, we have anecdotes.

Although Trump calls Tasers “an additional intervention tool that falls between the ultimate use of deadly force and other less-than-lethal interventions,” he is emphatic that they should be used exclusively by “sworn, certified and trained police officers,” not educators.

Many Ask Why Police Are in Schools at All

Many, however, believe law enforcement is missing the mark and argue that neither police nor weaponry belong in schools; others, however, take a middle position, advocating that law enforcement should be a last resort, utilized only when other types of mediation have failed since chemicals and stun guns have the potential to cause permanent physical and psychological problems.

Ebony Howard, an attorney at the Alabama-based Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), represented eight students in a lawsuit against a Birmingham school district over its use of mace. “One of them was KB, a pregnant African-American 16-year-old,” Howard told Truthout. “She was going from one class to another when a boy walked up to her and started calling her foul names like bitch and whore. She tried to get away from him but he and a group of his friends followed her.” Things got loud and a security officer showed up. According to Howard, “he told KB that if she did not calm down, he’d arrest her. He then sprayed her with mace.”

“In schools where the students are poor and mostly of color, police departments are criminalizing adolescent conflict.”

Fortunately, KB recovered and her fetus was unharmed, but a SPLC lawsuit challenged the officer’s handling of the altercation. A judge ultimately found that the officer’s use of mace constituted excessive force and while the ruling did not impose an outright ban on the use of chemical compounds in academic settings, Howard believes that the decision “sends a signal to other school districts” about calling police at the first sign of discord.

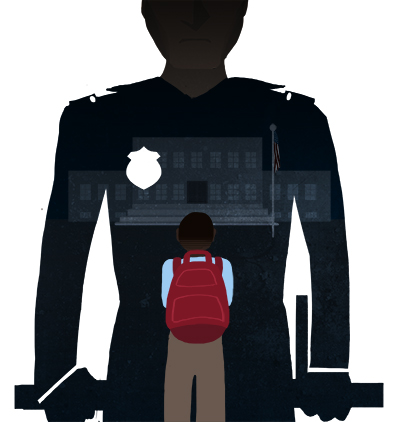

“Here in Alabama and across the country, in schools where the students are poor and mostly of color, police departments are criminalizing adolescent conflict,” Howard told Truthout. “Bias against children of color is woven into the fabric of the US. They are devalued.” This has become known as the school-to-prison pipeline and Howard is clear that it represents a gross violation of students’ rights to test boundaries and resolve conflicts on their own.

Still, Howard notes that if law enforcement personnel are going to be stationed in schools, they should be trained to work with young people. “They do not need to use a hammer to settle a conflict. They need to learn to negotiate and work things out without arresting anyone.”

Rukiya Dillahunt, a former teacher and school administrator from Raleigh, North Carolina who now works with the Education Justice Alliance, favors peace circles facilitated by mediators. “I remember doing this with two girls who’d gotten into a brawl over a boy. A social worker and peer mediator met with them to talk it out. There were rules. For example, they couldn’t call each other names and had to either talk directly to one another or to one of the other people in the room. From what I saw, the method worked. It gave the parties involved a way to process the issue. By the time they walked out, things between them were fine. Furthermore, they learned a strategy to settle disputes, and I hope, developed into adults capable of handling conflict and tension.”

This would not have happened had one or both been arrested, Dillahunt said. Suspension would have been similarly disruptive. “When kids are kept out of school they become demoralized and angry,” she told Truthout. “We have a block schedule, with 90-minute classes. If you miss one day, it’s like you’ve missed two. Not everyone can catch up, especially if they’ve been kept out for five or 10 days. Some kids feel like they’ll never pass, so rather than fail, they drop out.”

While some may re-enroll later, excessive discipline is associated with other negative consequences including increased aggression, anxiety, depression and suicidal ideation. These conditions, in turn, can lead to physical ailments, including liver and heart disease.

All of this, said Victor Vieth, director and founder of the Center for Effective Discipline at the National Child Protection Training Center, is completely avoidable if school personnel look at the underlying issues — including poverty, hunger, domestic abuse and homelessness — that typically cause students to act out. “If we simply respond with corporal or violent punishment we’re treating the smoke while ignoring the fire that underlies it,” he said.

This, of course, hurts students and their allies and can turn school from a place of excitement and wonder into a site of angst and upheaval.

Media that fights fascism

Truthout is funded almost entirely by readers — that’s why we can speak truth to power and cut against the mainstream narrative. But independent journalists at Truthout face mounting political repression under Trump.

We rely on your support to survive McCarthyist censorship. Please make a tax-deductible one-time or monthly donation.