Every year, major earthquakes, floods and hurricanes occur. These natural disasters disrupt daily life and, in the worst cases, cause devastation. Events such as Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy killed thousands of people and generated billions of dollars in losses.

There is also concern that global climate change will increase the frequency and intensity of weather–related disasters.

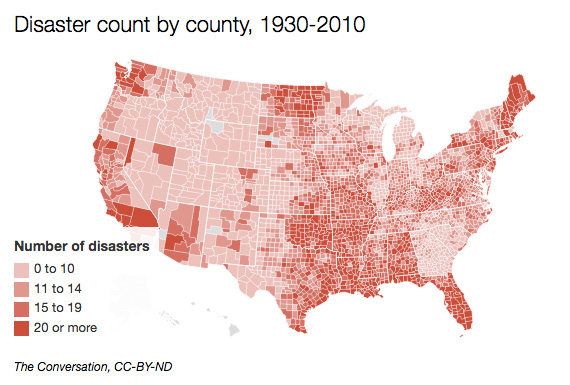

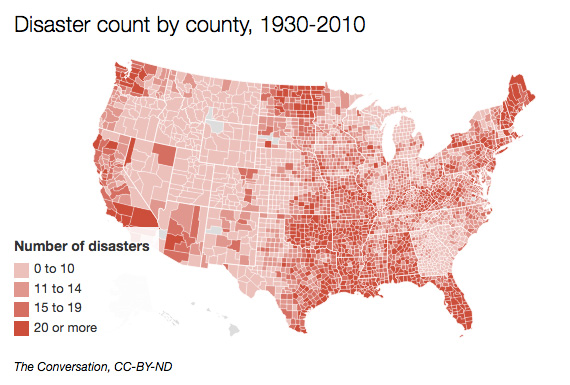

Our research team wanted to know how disasters affect people’s decisions to move in or out of particular areas. We created a new database that covers disasters in the United States from 1920 to 2010 at the county level, combining data from the American Red Cross as well as the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and its predecessors.

Our work shows that people move away from areas hit by the largest natural disasters, but smaller disasters have little effect on migration. The data also showed that these trends may worsen inequality in the US, as the rich move away from disaster-prone areas, while the poor are left behind.

(Graph: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND; Source: Provided by authors. Get the data here.)

(Graph: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND; Source: Provided by authors. Get the data here.)

Changing Risks

The US is a large country, with many regions that differ with respect to their risk of suffering a natural disaster. For example, coastal areas or areas in the flood plain of a river are more likely to experience a natural disaster, whereas areas at higher elevation are at lower risk.

Florida and areas on the Gulf of Mexico are wracked by hurricanes; New England and the Atlantic seaboard are battered by winter storms; the Midwest is a tornado-prone region; and counties along the Mississippi River are subject to recurrent flooding.

There are comparatively few disasters in the West, with the exception of California, which is affected primarily by droughts and fires. (However, the small number of disasters declared in the Mountain West may reflect the limited population in the area.)

Technological innovation has reduced our exposure to damages from disasters. Infrastructure in the US has been upgraded to reduce risks posed by flooding, high winds and earthquakes.

Furthermore, we now have access to real-time information that allows us to be aware of emerging threats. In Asia, for example, tsunami warnings are distributed by text message. Accurate early warning systems are likely to help us adapt, reducing the death count from disasters.

Yet, as of 2010, 39 percent of the US population lived in coastal areas that feature greater risks of hurricane, floods and earthquakes.

Add to this process the wild card of climate change. Basic climate science suggests that, as global greenhouse gas emissions increase, so too will the quantity and severity of natural disasters.

How Disasters Shape an Area

We used our new database to explore whether areas hit by natural disasters lost more residents to migration than areas that were comparatively calm.

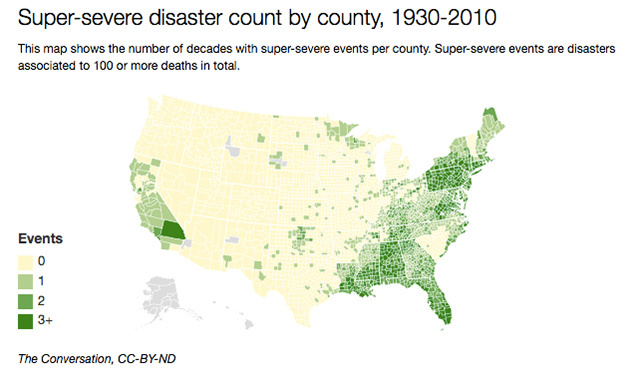

We found that, if a county experienced two natural disasters, migration out of that county increased by one percentage point, with the strongest reactions happening in response to hurricanes. This translates into a loss of around 600 residents from a typical county. The effect of one very large disaster — responsible for 100 or more deaths — was twice as big.

Poverty rates also increased by one percentage point in areas hit by super-severe disasters. That suggests that people who aren’t poor are migrating out or that people who are poor are migrating in. It might also mean that the existing population transitioned into poverty. We contrasted decades with high disaster activity to decades of comparable calm, thus making it unlikely that we are simply observing areas with higher poverty rates.

(Map: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND; Source: Provided by authors. Get the data here.)

(Map: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND; Source: Provided by authors. Get the data here.)

We were particularly interested in learning how the 1978 advent of FEMA — the agency that coordinates federal response to natural disasters — may have influenced the likelihood that people will migrate away following a disaster event. One might expect that residents would be less likely to move out of disaster-struck areas after this date, if FEMA increased payments of federal disaster relief.

Yet, we found that, if anything, residents were more likely to migrate out of counties struck by natural disasters after FEMA was created. This pattern is consistent with recent research documenting that the federal funds that flow to victims of disasters come mainly in the form of non-place-based programs like unemployment insurance and food stamps. It appears that many people in disaster-affected areas take the money and move to another county.

Finally, we compared the behavior of people living in low- and high-risk counties. People in areas very prone to suffer disasters — such as counties on a coastline or in a river plain — were three times more likely to leave areas following a severe shock than people in a typical county.

Rising Inequality

Despite the progress in preparing for natural disasters, our research suggests the poor will face growing exposure to natural disaster activity. Our research suggests that the rich may have the resources to move away from areas facing natural disasters, leaving behind a population that is disproportionately poor.

During a time of increased concern about income inequality and climate change risk, natural disaster exposure risk could become another cause of rising quality of life inequality between the rich and the poor. Our study suggests that areas that do not adapt to natural disaster risk will become poorer over time, as well-to-do residents move away.

![]()

24 Hours Left: All gifts to Truthout now matched!

From now until the end of the year, all donations to Truthout will be matched dollar for dollar up to $18,000! Thanks to a generous supporter, your one-time gift today will be matched immediately. As well, your monthly donation will be matched for the whole first year, doubling your impact.

We have just 24 hours left to raise $18,000 and receive the full match.

This matching gift comes at a critical time. As Trump attempts to silence dissenting voices and oppositional nonprofits, reader support is our best defense against the right-wing agenda.

Help Truthout confront Trump’s fascism in 2026, and have your donation matched now!