Nearly a week after ballots were cast in contentious midterm elections primarily seen as a referendum on the Trump administration, the race for Arizona senator was called in favor of the Democratic candidate, Rep. Kyrsten Sinema (now senator-elect) — the first Democratic win for this seat in three decades. In the final tally, Sinema won by about 53,000 votes out of more than 2.36 million votes cast — an incredibly close race that fell well within the reach of Native American voters in the state to deliver. The bulk of these Native American voters reside in just three counties (Coconino, Navajo and Apache Counties) that encompass the Navajo Nation, the largest Native American tribe in the United States, with a reservation that is slightly larger than New England and extends into three states. Based on US Census 2017 population estimates for those counties and 2010 Census ethnic/racial statistics, some 40,000 of the 65,858 votes cast for Sinema in those counties likely came from Native American voters.

Sinema’s victory points to a larger pattern shaping elections: In counties with Native American-majority populations in North Dakota, Montana and Arizona (all states that had closely contested Senate races this year), Democrats won upwards of 80 percent of the vote. Contrasted with neighboring white-majority rural counties which vote overwhelmingly Republican, Indian country is indeed another country. Moreover, in battleground states in the West where the push and pull between historically rural red voters and a growing population of urban blue voters leaves contests as close as a few thousand votes, the Native American electorate is often left to choose the winner.

The Heitkamp Race: Taking the Native Vote for Granted

Up until the day of the midterms, the country collectively held its breath as tribes in North Dakota heroically strove to get out the vote in the wake of a US Supreme Court ruling just weeks before the midterms. Their efforts received national and even international attention in the media for the first time after the Supreme Court upheld a North Dakota voter ID law that threatened to disenfranchise 20,000 voters. The law disproportionately impacted Native voters, as many residents living on rural and remote reservations in North Dakota rely on post office boxes and do not have street addresses, which the law required on identification to vote. Spurred on by such overt voter suppression by the state, in less than a week, tribal leaders and activists issued thousands of tribal photo identification cards for free, obtaining street addresses assigned by local 911 emergency coordinators. On the Turtle Mountain Reservation, some 5,100 votes were cast in this election — 80 percent voting for Democrat Sen. Heidi Heitkamp. On the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, which straddles North and South Dakota, nearly 1,500 votes were cast, doubling the average for a midterm election, and 84 percent voted for Heitkamp.

In the end, Heitkamp lost by more than 35,000 votes, as white-majority rural counties overwhelmingly voted for Republican Kevin Cramer. The total number of eligible Native voters in the state of North Dakota is 27,000 according to the 2010 US Census. Some credit Heitkamp’s loss to her vote against Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation to the Supreme Court. Indeed, as recently as April 2017, her approval rating was at 60 percent. However, there were certainly other reasons why some of Heitkamp’s constituents were not excited to vote for her. She was at home in the fossil fuels-based economy of North Dakota, and she was used to being called the “coal lady” due to her 11 years on the board of directors of the Great Plains Synfuels Plant, which manufactures synthetic natural gas from coal. She broke with her party to introduce a bill that would make it more difficult for federal agencies to use science to protect consumers, public health, worker safety and the environment. Trump’s friendly overtures to Heitkamp, including inviting her to ride with him on Air Force One and rumors he was considering her for a position in his administration, led her opponent, Senator-elect Cramer, to accuse her of being a “Republican wannabe.”

Despite this, Trump campaigned hard against her, visiting the state twice. When he sent his son Donald Trump Jr. to North Dakota, Heitkamp addressed the crowd via video to declare her support of the president’s agenda for the oil industry, including his efforts to lift the ban on oil exports. None of this saved her seat. Heitkamp’s loss poses the question: Should she have focused on protecting and turning out the Native American vote rather than taking flights with Trump?

Native Women’s Victories

Meanwhile, Native candidates saw significant election wins. In January 2019, not one but two Native women will be sworn in for the first time as congresswomen. Both are Democrats. Rep. Sharice Davids, a citizen of the Ho-Chunk nation, was elected in Kansas, a state with no substantial Native population, and Rep. Deb Haaland of the Laguna Pueblo tribe in New Mexico, a blue state with a significant Native population. Davids is also the first lesbian elected to represent Kansas in Congress. She defeated incumbent Kevin Yoder by more than 9 percent of the vote, despite a Kansas GOP official declaring on social media, “Your radical socialist kick boxing (sic) lesbian Indian will be sent back packing (sic) to the reservation.” In the end, Davids’s sexual orientation and citizenship in a Native nation proved not to be obstacles to winning office in a Republican-leaning state that has only drifted rightward over the past couple of decades.

A third Native American woman candidate for governor of the state of Idaho — 38-year-old Paulette Jordan, a former state legislator and tribal council member of the Couer d’Alene tribe and descendant of the 19th-century chiefs Moses and Kamiakin — did remarkably well, although she lost in a state many Democrats had long ceded to the Republican party.

Drawing on Native Culture

In Utah, sociology professor and citizen of the Navajo Nation James Singer ran as a Democrat for former Republican Rep. (now Fox commentator) Jason Chaffetz’s old seat. Although the first-ever Navajo candidate for Congress lost, he believes he won in other ways. Chaffetz had been notorious for being a ferocious opponent to the tribes’ national monument proposal for Bears Ears and Singer chose to run to challenge that stance. Chaffetz, who once chaired the powerful House Oversight Committee, created a furor last month and faced accusations of racism after sharing on Instagram a photo of himself hugging a cigar store Indian with the caption, “At Disneyland today with Elizabeth Warren.” In contrast, Singer refused to go negative in his campaign, and the debate between himself and Democratic incumbent John Curtis was widely noted in the press as a beacon of civility in politics.

“Thing I am most worried about is, we are going to get a lot of good Native candidates,” Singer said, “and instead of carving out their own power their own way, and rather than looking at our [Native] culture [for] ways we can improve things, they will become absorbed into the normal political establishment. It’s not just that I’m Native, but I’m Native and I have a certain perspective that comes from my culture.”

He explains that Navajo culture’s focus on harmony and balance, what is called hozho, means you address another person not as a Republican or Democrat but as a human being.

“We should be discussing and debating different ideas, changing scripts and show that people of color are not scary,” Singer said. “As Native people, we get known as the statistic [for] alcoholism [or] murdered and missing [people]. However, I think our cultural values can cure our people, the problems of the US, and help this country live up to the Constitution…. It means all of our narratives have a place in that story, the larger story.”

At the local county level in Utah, Navajo elder and leader for the Bears Ears National Monument Willie Grayeyes won his race for county commissioner. For the first time, San Juan County, Utah, will be led by majority Navajo leadership. In an ironic twist, when Trump reduced Bears Ears by 85 percent, he also placed the three San Juan County commissioners (who were then all anti-monument) to be on the commission managing the monument. He could not have foreseen that instead, he would be effectively putting even more pro-monument Navajos in charge of Bears Ears.

At this time, Navajo leaders in San Juan County are ecstatic yet wary. Challenges will inevitably arise as the white Republican leaders in Salt Lake City will feel threatened by the specter of Navajo political power wielded off the reservation.

Recent History and the Way Forward

Native voting power, of course, has been in the picture long before 2018.

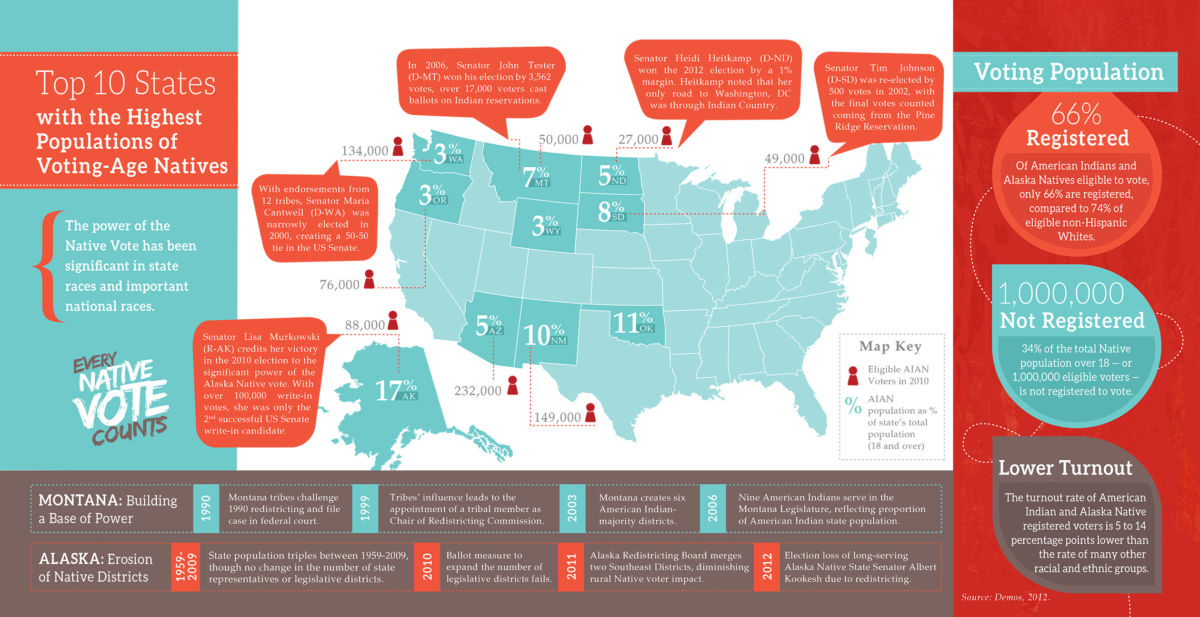

In 2012, Native voters in Montana delivered the Senate seat to Democrat Sen. Jon Tester when he won by just 3,562 votes. That same year, Heitkamp declared her path to Washington, DC, was through Indian country after winning by less than 3,000 votes. And in 2002, Democratic former Sen. Tim Johnson of South Dakota won by 500 votes, with the final ballots coming from the Pine Ridge Reservation where the Lakota people reside.

In 2010, Sen. Lisa Murkowski lost the Republican Party primary in Alaska and was forced to run as a write-in candidate. She credits her success largely to the support of Alaskan Native corporations and voters, and is only the second write-in candidate to have ever been seated in the Senate in US history. But even in their support of a Republican candidate, Native voters have different priorities for their elected officials than their white neighbors. Murkowski’s vote against Kavanaugh has been largely credited to pressure applied by her Alaskan Native constituents.

Democrat Tester won in Montana, despite four visits to the state by Trump and a widely shared photo which featured Crow leaders in full eagle feather headdress prominently seated behind Trump speaking at an event in support of his Republican opponent, Secretary of State Matt Rosendale.

The sight of this recalled for many Native Americans how the Crow “scouted for Custer” at the Battle of the Little Bighorn (called the Battle of Greasy Grass by the Lakota) against Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. (The tribe has a long and well-known history of being at odds with every other tribe in the region. Their leaders’ support of Trump must be understood in that context. The Crow have never lived down scouting for Custer and being on the wrong side of the greatest victory in the 19th century Indian Wars.) Many tribal members, however, were outraged by their leaders’ support of Rosendale, and Big Horn County — which contains most of the Crow Nation — voted overwhelmingly for Tester by 64 percent. In the end, Tester won by slightly more than 15,000 votes with about 8,000 coming from solidly Democratic Native voters on three reservation counties (Crow, Blackfeet and Fort Peck).

With the 2018 midterms now behind us, it’s time to look forward. If the midterms were, in part, about “Making American Native Again,” our eyes should be on what’s next. Will a growing number of candidates reach out to their Native constituencies? If they do, will they work to keep promises they’ve made, after Election Day? The influence of the Native vote should be a wake-up call for politicians – not only in terms of campaigns, but also in terms of the policy that follows.

We have 8 days to raise $48,000 — we’re counting on your support!

For those who care about justice, liberation and even the very survival of our species, we must remember our power to take action.

We won’t pretend it’s the only thing you can or should do, but one small step is to pitch in to support Truthout — as one of the last remaining truly independent, nonprofit, reader-funded news platforms, your gift will help keep the facts flowing freely.