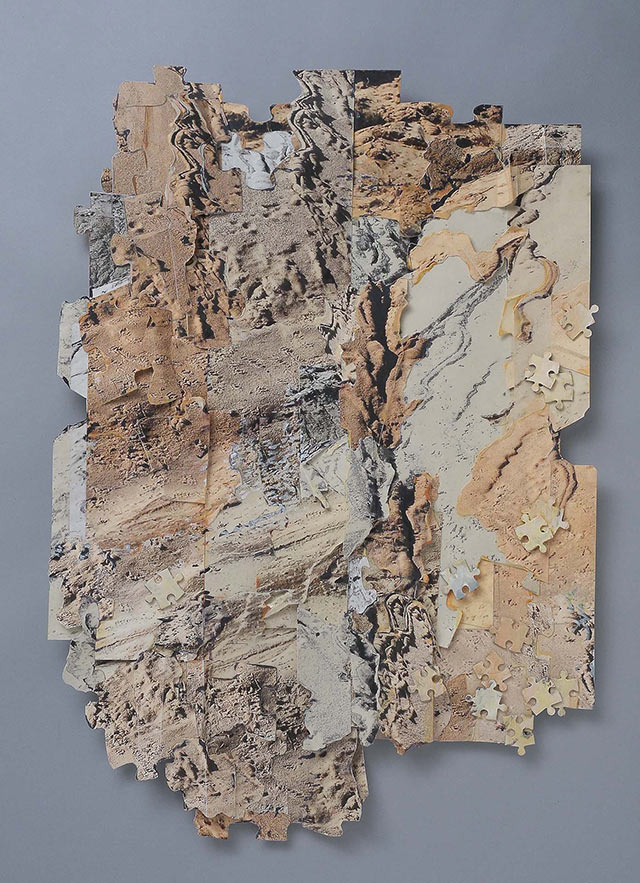

Hanging in the Atlantic Wharf Gallery, off the lobby of a posh Boston office building, in a small show entitled “Islands on the Edge,” there’s a collage that looks both like a map and a jigsaw puzzle, with small overlapping, multitextured leaves in tones of taupe, pearl, brown and dark gray. Entitled “Restless Sand 2,” it is part of a series by Phyllis Ewen, now in her fifth decade of work and one of New England’s most arresting artists.

Ewen, my friend of many years, lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She is one of the many artists who are responding as climate change and political disasters proliferate. Her present show was hung in August 2015 and will be up until September 25. The artist’s work is in the collections of Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, Boston Public Library and Harvard University. It has been shown in many East Coast galleries and in Cuba, which she visits frequently.

Mutability – the impermanence of what humans have taken for granted, even of rivers and oceans – is an overarching theme.

Ewen brings ideas about climate change and human struggles over water, the planet’s most precious resource, to her viewers. Coming of age in the 1960s, she was active in the women’s movement and resistance to the Vietnam War, and like many of us still works with these and similar political concerns in mind. But her work transcends easily definable opinions because of her refusal to make it a mere messaging vehicle.

“Restless Sand 2” is what the artist calls a “sculptural drawing,” one of a small panoply of works instantly recognizable as Ewen pieces with their juxtapositions of maps, puzzle parts, overlaid images and printed texts. What strikes the viewer is the meticulous craftsmanship here – for example, the care taken to create multiple layers in which each “puzzle” piece is juxtaposed against another to form what looks like cascading fragments of tree bark or, viewed as a whole, a landscape. So does a similar piece, “Liminal Break 2,” with its suggestion of craggy outcroppings, plateaus and shores in the colors inspired by their counterparts in nature.

Land & Water — Liminal Break #2. Artist: Phyllis Ewen. (Credit: Dean Powell)

Land & Water — Liminal Break #2. Artist: Phyllis Ewen. (Credit: Dean Powell)

Most recently, Ewen has been constructing her sculptural drawings from photographs she has taken of sand and dunes along the coasts of New England, but many images she has used over the years come from meteorological textbooks, charts of storms in oceans, photographs and bits of text. The pieces aren’t big, but they convey a sense of large planetary forms – rivers, shores, mountain ranges. Mutability – the impermanence of what humans have taken for granted, even of rivers and oceans – is an overarching theme, and for the last 10 years water has been central. Water, in the words of the text accompanying the drawings, “becomes a metaphor for a life force that resists being controlled” but that nonetheless is altered through human impacts.

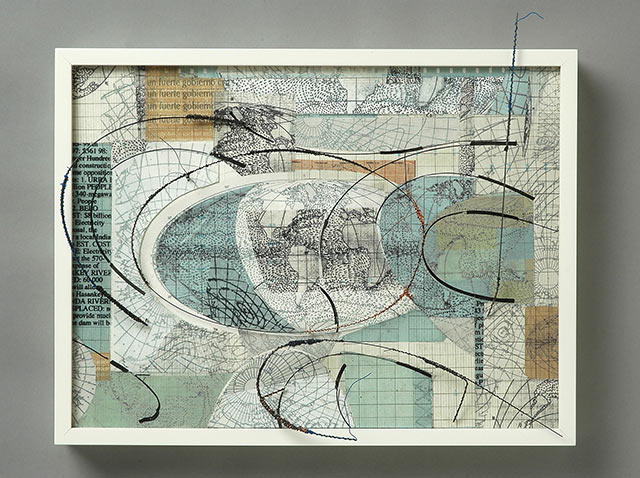

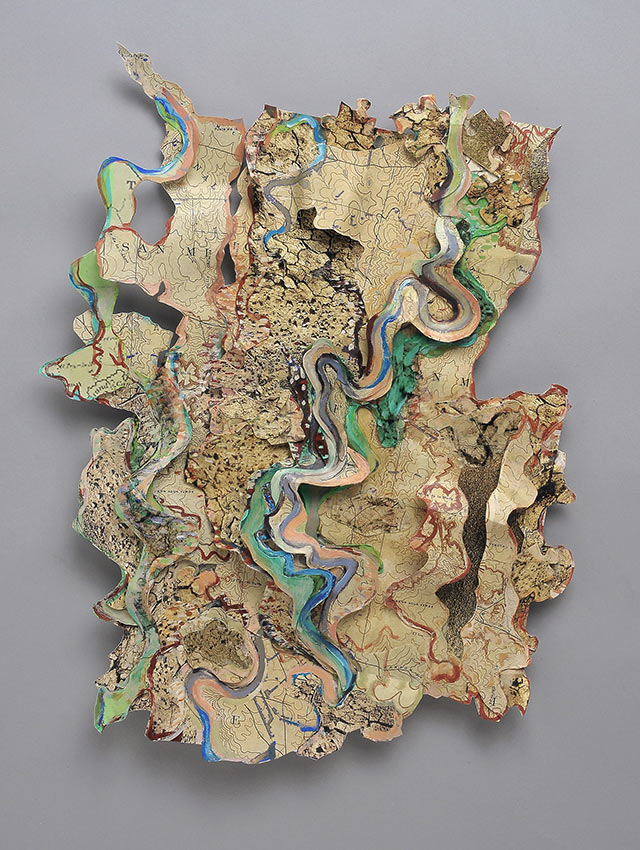

In “Global Currents 2,” Ewen worked on weather-graphing paper, creating mapped globes with inserted bits of wire and large inked swirls that escape the borders of the piece as if driven by the forces of water and wind. The “Global Currents” series, says Ewen, is about “power and who controls water resources” – through dams, for instance, which feature prominently here. Political conflict is also portrayed. Ewen says that “Aggravated Drought,” a diptych in shades of brown and turquoise with text fragments, maps and swirls of ink, is about Palestine, though this isn’t immediately apparent, nor are the artist’s own anti-occupation sentiments. “Tormentas de Polvo,” another piece in the series, “isn’t just about the war but about the conflict between Iraq and its neighbors over the Tigris and Euphrates rivers.” A group called “Thinking Like a River” consists of pieces in desert colors and in Ewen’s words is “about dry rivers. Life-giving rivers have been polluted, exhausted by human intervention.”

Global Currents #1. Artist: Phyllis Ewen. (Credit: Dean Powell)

Global Currents #1. Artist: Phyllis Ewen. (Credit: Dean Powell)

Water “becomes a metaphor for a life force that resists being controlled.”

Climate change is often present, for example, in “Northern Waters 1,” with its stormy, concentric swirls, its black and white map sections and its scattered, patchwork-quilt array of blues and aquas. “I do feel anxious and very scared, worried, about where the world is going,” she says. She began “Northern Waters” a day before Hurricane Sandy struck New York. “The fact that I started it coincidentally when Hurricane Sandy hit clarified that I was making visual the realities of rising seas and drying rivers.”

Jill Connor, a New York-based art critic and curator, writes that Ewen’s sculptural drawings “explore the fast-changing phenomenon of global warming, highlighting the effects of rising waters and parched earth. Each piece consists of dissected maps, charts and photographs, with handmade jigsaw fragments that further articulate the three-dimensional surface and ripple throughout the composition, alluding to the crumbling world, while coated in either aquatic or earth tones.”

Thinking Like a River — Disierto. Artist: Phyllis Ewen. (Credit: Dean Powell)

Thinking Like a River — Disierto. Artist: Phyllis Ewen. (Credit: Dean Powell)

Social and environmental concerns have always been latent in Ewen’s work. Early in her career she created a series of portraits of women sitting under hair driers. I had one showing a bulky, graying woman in late middle age gazing out from under the drier’s plastic shield, curlers in her hair. It made a forceful statement about real women as opposed to photographs of models. “The discussion [in the women’s movement] in the 1970s was how we were being forced into certain beauty standards by the media. But that’s not the only reason why women go to the beauty parlor. I thought that was the only time women could get taken care of.”

Northern Waters #1. Artist: Phyllis Ewen. (Credit: Dean Powell)

Northern Waters #1. Artist: Phyllis Ewen. (Credit: Dean Powell)

Ewen knows what it means to have little time to take care of herself. In 1979, her daughter was born and in 1983, her son. She was teaching at Massachusetts College of Art. She had been working as a photographer on a series about working-class family camping, but after her daughter was born she changed her medium. While weaning her daughter, she began using diapers as material for her art. Through patchwork, safety pins, wires, gold thread and metal leaf, wrote a critic in 1994, reporting on a show called “Nine Months: Art and Pregnancy,” the diapers became “delicate, exquisitely crafted geometric designs” evoking “the peace and fulfillment of nurturing” in which Ewen’s roles as mother and artist were reconciled. Ewen sees them differently. The “Nappy Pieces,” as she called them, were “about being ripped – they were very vaginal, the little wires were very pubic. They were fragments – that’s a way I look at life a lot.”

“I was making visual the realities of rising seas and drying rivers.”

Later she moved from home to the outdoors, creating other fragments – installations in which there was a playful interchange between nature and artifice. The series “Green Thoughts,” with its reference to the English renaissance poet Andrew Marvell’s The Garden, used Astroturf to create large, vegetable-like forms. In one, three Astroturf chairs seem to take shape organically, pseudo-plants rising from a very real grassy area beside a stream. In another, “Saltmarsh Pillows,” she placed a group of large Astroturf pillows in the midst of a Cape Cod salt marsh. As vegetation surrounding them withers and dies and the snow falls, the installations “become home to caterpillars and collect the detritus of nature.” Thus, they show the imagination “interact[ing] with the natural in unpredictable ways – as the natural world is always in contact with human intervention.”

Green Thoughts — Indoor/Outdoor Garden. Artist: Phyllis Ewen. (Credit: Dean Powell)

Green Thoughts — Indoor/Outdoor Garden. Artist: Phyllis Ewen. (Credit: Dean Powell)

The sheer variety of materials Ewen uses is striking, as is her skilled manipulation of them. In several groups (“(E)motion,” “Pipeline Dreams” and “The Space Between“), she has cast latex into small forms looking like beakers, hour glasses, funnels and tubes, suspending them against texts and illustrations drawn from scientific textbooks. Thus, she has created “a three-fold visual language: object, written word, and mathematics.” This group of forms suggests ideas of containment here – filling, emptying, pouring, holding; the texts in the pieces “are fragmentary, each chosen for its emotional resonance and reference to the human body….” Of the fragmentation, Ewen says, “I often work in series, and my paintings have parts to them where a fragment was broken into four parts and then put into a single piece. I feel it’s how I experience my life. There are fragments and I’m continually trying to pull [them] together.”

Overall, the artist’s work over the past eight years is most akin to the early “nappy” or diaper phase of her work because “it’s wedding some of my political concerns and my art.” A poet who interviewed her in 2012 wrote that in Ewen’s art, water “represents consumerism, waste, abundance, and scarcity,” with “collages of maps and texts to explore the divisions (dams, man-made boundaries) humans have imposed on world culture.”

Of the sheer beauty and elegance of her works, Ewen says, “I feel that I try to create something that is beautiful enough to look at, and get us through thinking about what it’s showing.” What does she want her viewers to take away with them? “I want people first to look and be affected emotionally, and then ask questions. Enough people have said this to me, that my work takes time [to absorb], which means you have to spend time with it. And I like that.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $17,000 by midnight tonight. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.