Puebla, Mexico — Canadian gold mining company Almaden Minerals has announced that it will seek arbitration against Mexico, demanding damages of at least $200 million for “financial losses” after its mining concessions in the mountains of Puebla State were canceled.

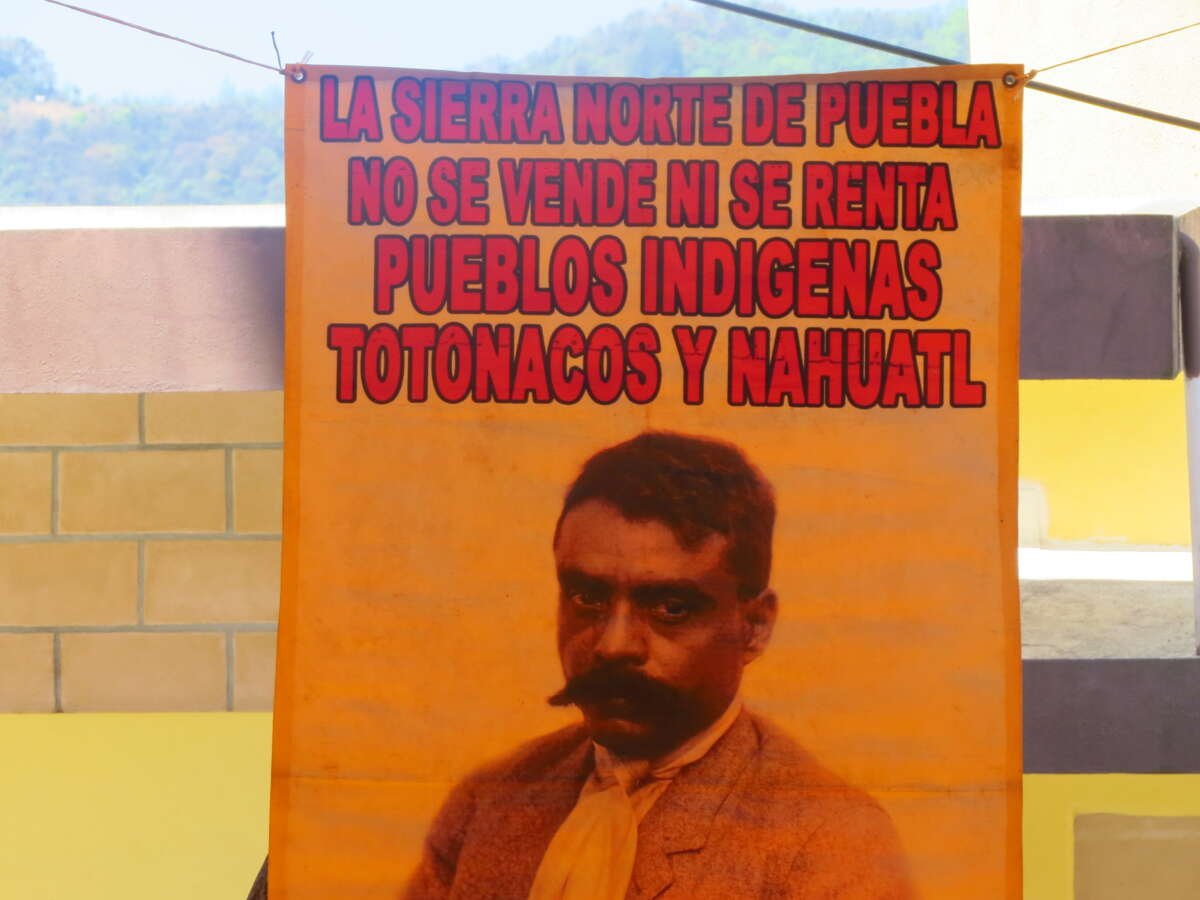

But, having lied and asserted there were no Indigenous communities in the area, the company had its concessions canceled by the Mexican Supreme Court due to the legally required Indigenous consultation process not having occurred. That followed years of resistance by Nahua and Totonaco Indigenous communities in the affected municipality of Ixtacamaxtitlan, in the Sierra Norte mountains, concerned about irrversible environmental damage.

Almaden has been operating in Mexico via its subsidiary Minera Gorrión, on a single project: the Ixtacamaxtitlan mines. It announced on June 17 that it was seeking arbitration against Mexico under the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) — a so-called free-trade agreement that includes Mexico and Canada. The company is claiming financial losses from the Mexican government, including the voiding of mineral titles and refusal to issue an environmental permit. It has filed its request for arbitration with the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Dispute (ICSID), and on June 27 announced it had $9.5 million in litigation funding.

Almaden had not yet started its open-pit mining when the concessions were canceled. Typically, mines spend five to 15 years to go from an initial exploration phase to full-scale mining. Almaden arrived in Mexico in 2001, when then-President Vicente Fox gave it an exploration concession. It began exploration of two mountain areas covering 14,229 hectares belonging to 15 Indigenous communities in 2009, and completed its feasibility study in 2018. In that study, it claimed that there were enough minerals available for an average annual production of 108,500 ounces of gold and 7.06 million ounces of silver.

Marketing Environmental Destruction

Even at the exploration stage, Almaden was already causing severe damage. The Ejidos Union pointed out discrepancies between the amount of drilling that Almaden reported to its shareholders and the amount authorized by Mexican authorities, and that the drilling damaged aquifers, depleted springs and killed livestock. (Ejidos are communal lands awarded by the government to mostly Indigenous communities that lacked colonial documentation of their collective ownership.)

Communities spent four years conducting their own human rights impact study, and found that there were negative impacts on the environment, water and health during the exploration stage, as well as a risk of forced displacement.

Hence, the company worked hard to get communities on its side, activist leader Miguel Sánchez Olvera told Truthout. Sánchez, a member of the Totonaco Regional Council and Indigenous Totonaco farmer in Olintla, in the Sierra Norte mountains, said the company would hand out presents on Mother’s Day and at other events.

“That’s how they work, dividing [communities] and offering support. They were building some infrastructure for drinking water so that they could be accepted, but with time, those people who supported them stopped, despite all their presents, because they saw that the company is here illegally and doesn’t benefit the people,” Sánchez said.

Having lied and asserted there were no Indigenous communities in the area, the company had its concessions canceled by the Mexican Supreme Court.

Even after the Supreme Court ruling, Sánchez’s organization (the Totonaco Regional Council) and others such as the Ejidos Union, the Tiyat Tlali Council, the Cooperatives Union Tosepan Titataniske, the Atzin Movement and the Tajtolmej Taltipak Collective, denounced the company’s escalating campaign to divide their communities and win them over financially by supporting religious events and gifting fertilizer, money, and more, in the hope of continuing to operate the mine anyway.

Years of Resistance to Prevent Further Damage

Community, activist and research organizations have spent years organizing forums, protests, informational assemblies, road blocks and protest convoys, and carrying out legal action, including the court case led by the Nahua community and the Tecoltemi ejido. In 2015, community assemblies declared their territories “mine-free” as an expression of their self-determination.

The goal has been to stop Almaden from reaching the operation stage. The mine, Sánchez explained, is located in a catchment area of the Apulco River. “And that river connects with the Ajajalpan River and then four others, so if there was an accident, the pollution would travel all the way to the Gulf of Mexico.” He explained that just seeing the animals dying and the chemicals used in the exploration drilling demonstrated to people how bad it would be if mining began.

“We’re united, across the Sierra Norte mountains of Puebla, to defend the water and the land,” he said.

Nonprofit organization PODER found that operating the mine would put local domestic and agricultural water supplies at risk, as the underground and dam water available wouldn’t even meet the amount required by the mine. Other similar mines, such as Equinox Gold in Guerrero, caused a “total modification of the landscape, displacement of farming activities,” and skin and eye problems in children.

The toxic substances used in gold mining, like mercury and cyanide, can end up in the soil and water. Producing enough gold for one wedding ring generates 20 tons of waste, while the global gold mining industry produces 180 million metric tons of toxic waste per year.

Almaden conducted its environmental impact study in 2019, but Mexico’s environmental authority rejected it, saying the company failed to present “clear objective information” and that the study didn’t provide information required by law.

Indigenous Consultation

In 2019, 40 communities organized into the Ejido Union publicly denied their consent for the Almaden mine. Mexico is a signatory to the International Labour Organization Convention 169; the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, which establishes the right to free, prior and informed consent over any projects affecting Indigenous territory. That right gained constitutional status in Mexico in 2011, with a detailed protocol established in 2013.

The drilling damaged aquifers, depleted springs and killed livestock.

Asked about Almaden demanding $200 million from Mexico, Sánchez said, “If I were president, representing my country, I’d tell them [Almaden] to go to hell … but the problem is that international laws all support the big corporations, never the people. But if they came here, where we are very organized, we wouldn’t pay them a cent. Because we never gave them permission to buy our land. That was illegal, because it was ejido land.”

Nevertheless, in a December 2020 press release, the company lied about there being “no need for consultation, as the data analyzed indicated the absence of an indigenous (sic) population in the area of the project.” Mexico’s National Institute of Indigenous Peoples confirmed that the company’s statement was incorrect, and that there are 71 localities with Indigenous populations in the Ixtacamaxtitlán municipality.

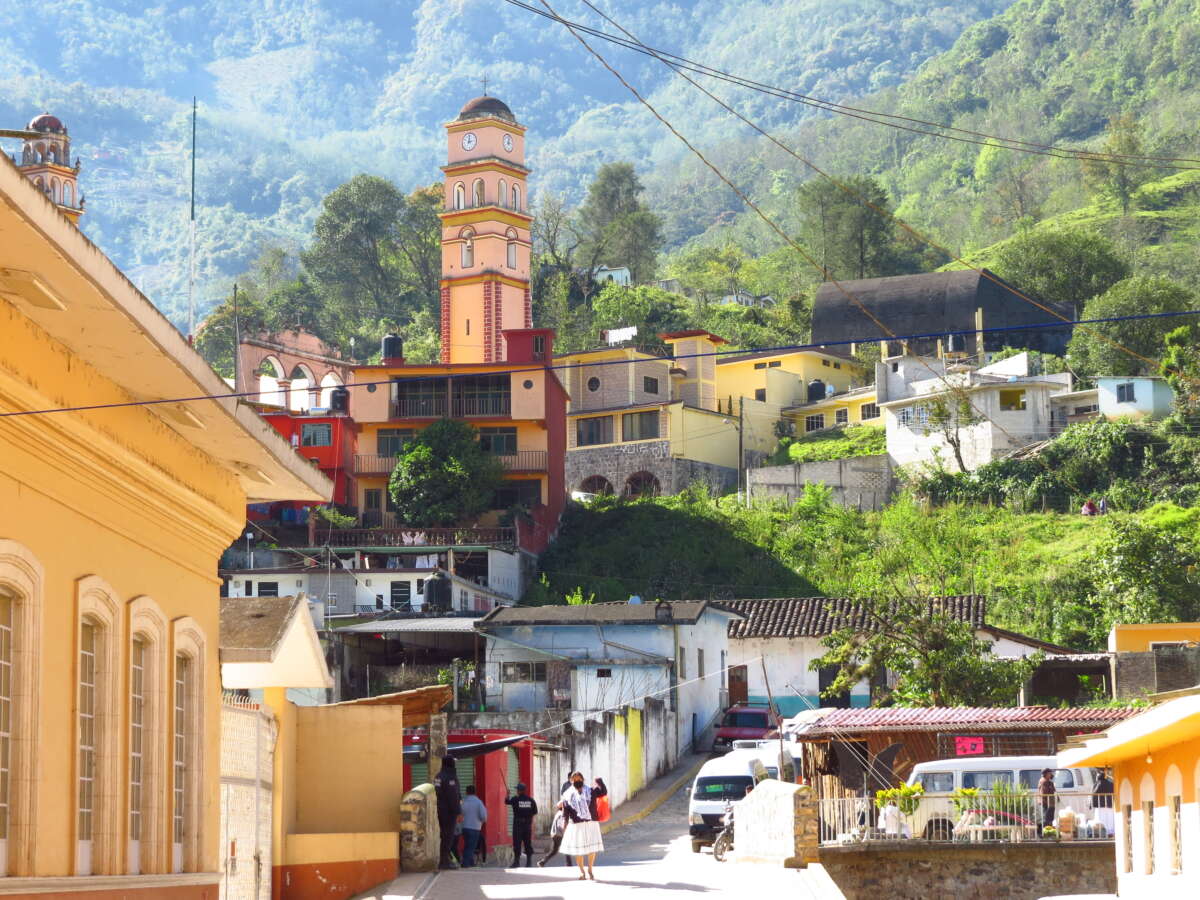

In Ixtacamaxtitlán, Indigenous identity and culture are part of daily life, and reflected in how people organize, farm and relate to the land. Most people there live in moderate to extreme poverty, and depend on growing corn, beans, zucchini, chilies and fruit.

Truthout contacted Almaden Minerals via email and multiple phone calls for further comment but received no response. However, in a recent press release, Almaden Chair Duane Poliguin claimed:

The Ixtaca project was poised to become a significant success for shareholders, local communities, and Mexico. The company followed best international standards and practices, including through adoption of dry stack filtered tailings, ore-sorting, and water management plans that could have improved water availability for local communities…. I lament most heavily this outcome for local people, whom we have worked very closely with over the past two decades, and who have become our friends. They now stand to gain nothing from the Ixtaca project which was developed and designed with their assistance.

Victory for Indigenous and Environmental Activists

It took seven years for the lawsuit that activists and communities filed in 2015 to eventually reach the Supreme Court, which ruled that, “Mexican authorities are obliged to enforce the right to prior, free, and informed consultation with Indigenous peoples when issuing mining concession titles that affect their territory.”

The economy ministry then followed through on the ruling in July 2022, ordering the cancellation of Almaden’s two mining concessions. Later, in April 2023, a Puebla court declared that the Supreme Court ruling had been implemented and that with it, no mining concessions could ever be awarded in Ixtacamaxtitlan, based on the Mining Law. The communities then demanded that Almaden leave their land immediately.

“In Ixtacamaxtitlán we refuse to sacrifice our lives, to pay with our lives so that capital can be multiplied,” wrote Alejandro Marreros Lobato of the Ejidos Union.

“Free” Trade Could Win

The CPTPP, through which Almaden is essentially suing Mexico, is very similar in nature to the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which replaced the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). The CPTPP reduces or eliminates barriers to trade and investment, and identifies health and the environment as technical barriers to trade, while also acknowledging the right of governments to regulate in the public interest.

However, economic dependence, debt and power inequalities mean that Global South countries are not equal when these trade agreements are negotiated. Agreements like NAFTA, CPTPP and USMCA put power into the hands of foreign companies in Mexico by deregulating labor rights and environmental standards, spurring privatization of the land, and favoring U.S. and Canadian corporate investment, agriculture and monoculture. NAFTA saw Mexican wages drop by 27 percent. The agreements encourage corporations to extract profits at the expense of citizens, demonstrated by Almaden suing a struggling country for $200 million so that it can take that country’s gold.

Community, activist and research organizations have spent years organizing forums, protests, informational assemblies, road blocks and protest convoys.

Almaden “can make all the mistakes in the world, they can break all the laws — both national and international — but it’s us that the police end up beating up,” said Sánchez.

Mexico has one of the highest rates globally of murders of environmental activists, around half of whom are Indigenous. Two police were recently detained for allegedly killing two rural activists from Puebla and Veracruz who were protesting water contamination by pork company Granjas Carroll.

Had Almaden started operating and destroying land and rivers in the Sierra Norte, all of its profits from Mexico’s gold and silver would have gone to its Canadian and overseas shareholders. This pattern is typical of mining and other companies that extract resources from the Global South. Newmont Corporation, for example, a U.S. company and the world’s largest gold miner with $11.8 billion in sales last year, mines its gold largely in the Global South — in Mexico, Ghana, Argentina, Suriname, Peru, Dominican Republic and Papua New Guinea — as well as in Canada, the U.S. and Australia. Its major shareholders — who rake in its profits — are in the U.S.

From 1960 to 2021, rich countries drained $152 trillion from the Global South through resource robbery, selling the Global South’s raw materials, exploiting labor and economically benefiting from manufacturing in the Global South. That is around $2.2 trillion annually, enough to end extreme poverty globally many times over.

Almaden’s suit is only the latest in a long legacy of exploitation. In 2001, “free” trade saw U.S. corporation Metalclad awarded $16.5 million. The local government expropriated the company’s hazardous waste landfill near mines in San Luis Potosí, Mexico, but under NAFTA was punished for taking U.S. investors’ property. After that, Mexican authorities feared objecting to U.S. or Canadian companies.

Sánchez said the Almaden arbitration could see the Mexican government cracking down on land defenders harder, “but we have to continue struggling … by working the land, we are planting new types of awareness, teaching the youth to love the land and respect life.”

Press freedom is under attack

As Trump cracks down on political speech, independent media is increasingly necessary.

Truthout produces reporting you won’t see in the mainstream: journalism from the frontlines of global conflict, interviews with grassroots movement leaders, high-quality legal analysis and more.

Our work is possible thanks to reader support. Help Truthout catalyze change and social justice — make a tax-deductible monthly or one-time donation today.