Support justice-driven, accurate and transparent news — make a quick donation to Truthout today!

The handcuffs just slipped off her wrists; in fact, Desre’e Watson was so small that they had to handcuff her by her biceps to haul her down to the station, the Florida police chief told The New York Times in 2007. No one could calm her tantrum, so the cops charged her with battery on a school official, disruption of a school function, and resisting a law officer. She was fingerprinted, had a mug shot taken and was kept briefly in a jail cell. She was 6 years old.

The ACLU reported in 2013 that a 5-year-old boy in Mississippi, who didn’t own a pair of black shoes, couldn’t follow the school dress code; so, to help him out, his mother colored in his red and white shoes with black magic marker. While some might call this an issue of finances, the school decided to send him home in a police car.

To determine culpability, we must take “developmental considerations into account” when assessing juveniles. They are not little adults.

Unfortunately, these are not isolated incidents. Many sources, such as The New York Times, Chicago’s Project NIA and the Justice Policy Institute have reported that the legal system has often become a go-to for even the most minor transgressions of children, particularly children of color. However, according to an interview with Naoka Carey, executive director of Massachusetts Citizens for Juvenile Justice (CfJJ), it is a mistake if we think our “juvenile justice system is designed for little kids … It is not.” Carey added a developmental look at kids instead of “an interventionist model” is best for all juveniles. Even if cases against children are dismissed, how can such interactions – being handcuffed, driving in a police car, talking to a strange man called a “lawyer,” without parents present, being arraigned in a courtroom, or sitting in a cell alone, not create more harm for children?

Now, Carey said, Massachusetts is trying to pass an omnibus bill “to promote transparency, best practices, and better outcomes for children and communities,” but advocates, experts and those swept up in these practices are wondering what it will take to see and treat our kids as kids. When will policy makers concur that the criminal legal system is not the best answer for kids in conflict with authority?

Where Childhood Ends?

Children as young as 6 can go to court in North Carolina, while four states – Massachusetts, New York, Connecticut and Rhode Island – set the youngest age at 7. Thirty-three states set no age for court involvement, but according to the National Center for Juvenile Justice, that means age 7 is the default, or “the youngest age under common law where a child would be considered capable of criminal intent.”

“Criminal intent” or the idea that a child can intend to commit a crime has come under great scrutiny in recent years. Judge Jay Blitzman, first justice for the Middlesex Juvenile Court in Massachusetts, in an interview with Truthout, pointed out that a number of Supreme Court cases “have essentially created a new kind of constitutionality for children so that they are accountable, but not to the same degree as adults.”

“Models are varied,” said Blitzman, noting the problem of not having a national consensus on how to treat children in the legal system. “So when you look at juvenile justice from a national standard, there are 51 different standards. Each is subject to jurisdiction – which may seem arbitrary.”

The legal system is now informed by the work that the MacArthur Foundation’s Network on Adolescent Development and Juvenile Justice has done since 1997. It has shown how brain science can support decisions by assessing competency: For example, before the age of 16, kids are much less likely to understand the process of justice. The findings hold that to determine culpability, we must take “developmental considerations into account” when assessing juveniles. They are not little adults.

When Truthout asked, “Can we consider children capable of determining the difference between right and wrong, of forming a ‘guilty mind’ when they break a law?” Judge Blitzman was quick to point out that there is no “certain age [where one is] more or less liable. It’s an evolving process, not a dichotomy.” Maturation occurs at different rates, Blitzman noted, adding, “It’s a question of the quality of culpability.”

The actual age number for a child to be considered culpable seems somewhat arbitrary, even among experts. Carey and others want Massachusetts to raise the lower age of juvenile court jurisdiction from 7 to 11. Judge Blitzman told Truthout, “Youth below the age of 10 are not competent to stand trial.”

Since much of this neurological research has been done on teens and not on younger children, one can only assume that its application is murky terrain – a terrain that our punishment system has shown time and time again it is not particularly well-equipped to navigate.

Police in schools have led to “youth being arrested for disruptive rather than dangerous behavior.”

A report published in March, 2015, from the Presidential Commission for Bioethical Issues, and an article about the consequences of that report in Pacific Standard Magazine suggest that, “The rise in neuroscience in courts warrants caution.” Certainly it is positive that emerging science has determined that courts can’t sentence children younger than 18 to the death penalty, or to life in prison without parole. While judicial decisions citing neuroscience doubled from 2007 to 2011, scientific-looking evidence doesn’t always help young defendants. Per Pacific Standard, “Prosecutors can use neuroscience evidence to argue that somebody is naturally aggressive or dangerous and needs more restrictive punishment.”

“We Don’t Treat Children Who Are Black as Children”

“Young children’s misbehavior isn’t a mark of their character; it’s a mark of their childhood,” Joshua Rovner, state advocacy associate of the Sentencing Project, told Truthout in an interview. Rovner also noted, “If kids have been arrested, it is more likely they will be arrested again.”

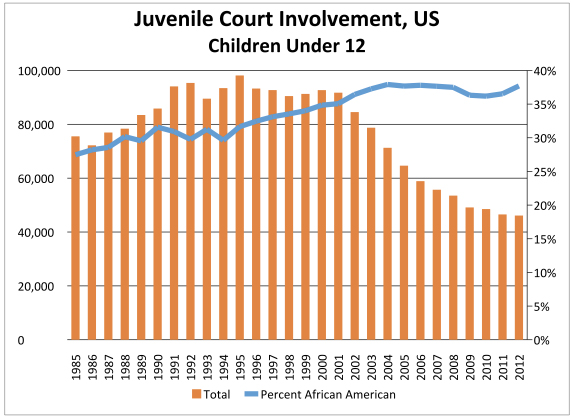

He also pointed out in an email that annually, the number of kids younger than 12 who are referred to a juvenile court is approximately 40,000 (See graph below).

The trends nationally are going down, but proportionally for African Americans, the rates are going up. Rovner wrote, “In 2012, 38 percent of the children under 12 who were processed by juvenile courts were African American. (Compare that to the total population of that age: Among all children, ages 6-11, roughly 16 percent are African American.)”

Mariame Kaba, founding director of Project NIA in Chicago, which aims to end youth incarceration, said in a phone interview with Truthout, “At a certain point, age is irrelevant. We don’t treat children who are Black as children.” The American Psychological Association underscored this with its 2014 report that Black boys as young as 10 are more likely than their White peers “to be mistaken as older, perceived as guilty, and face police violence if accused of a crime.”

Arresting kids will never get to the bottom of the problem, concluded all those whom Truthout contacted. “Kids are in conflict with the law because of unmet needs,” wrote Kaba and Dominican University professor Michelle VanNatta in a 2013 report on the state of youth justice in Chicago. From their findings: Kids who act out may be facing overcrowded school classrooms or have crises in their families; there may be a lack of recreational and after-school activities available; students may be homeless; school resource officers and police patrol schools, often threatening, rather than protecting children.

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, nearly a third of primary schools have some form of security personnel, which includes school resource officers. But research by the Justice Policy Institute has shown that police in schools have led to “youth being arrested for disruptive rather than dangerous behavior.”

Additionally, Suffolk University professor Susan Sered, coauthor of Can’t Catch a Break: Gender, Jail, Drugs, and the Limits of Personal Responsibility, noted that those who advocate for “treatment” need to realize that the mental health system is not always benign. She has seen how “treatment for juveniles typically involves enormous amounts of psychiatric meds.” This is a concern, she told Truthout, since, “No one knows the long-term impact on growing juvenile brains.” Sered said, “The root of the issue is not behavioral if kids are living in communities where 40 percent of the men can’t find jobs, and there are toxins in the environment and violence in the streets.” How will psychiatric meds solve those problems?

A Case Study

Before Meri Viano began working as the director of community outreach and partnership at the Parent Professional Advocacy League in Massachusetts (PPAL), the mother of three children landed there because her kids needed help. She blogged that she once tried to go grocery shopping at 11 pm “to limit the number of customers who point[ed] at [her] and [said] ‘That’s the mom with the unruly child.’ “

In an interview, Viano discussed how a police officer told her personally that her 8-year-old son needed what was then called a CHINS (Child in Need of Services). With that, she said, he “would have come under immediate court involvement” – meaning her child couldn’t be helped, and he would have to go into the court system. This, Viano concurred, could have been horrendous: “It ultimately would have led to my child appearing in front of a judge, with the possibility of probation or a placement out of the home.”

She had no intention of allowing her child to be placed out of her home. She knew that her kids needed connections with family and community, so removing them from their environment would make things worse. She went to find out what alternatives there were for her children by volunteering at Massachusetts’ Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative (JDAI). As a JDAI volunteer, she was able to get enough information to keep her child from appearing in court. Now, she works with parents on keeping their kids out of the court system.

Viano said navigating the legal maze and understanding court language is a big hurdle for parents. She teaches them how to coach their kids, since Massachusetts – like all but four states – does not have parent-child privilege. At PPAL, after Viano assists parents with advocacy for their kids, she also trains them to work to change the juvenile legal system.

There were almost 500 children arraigned: Five of these were 8 years old; 15 were age 9; 20 were 10 years old; 118 were 11 yeara old; and 325 were age 12.

Lack of parent-child privilege or the fact that parents cannot be a part of the lawyer-child conference is particularly challenging for attorneys who work with the very young. “A child of 9 is scared and often has no idea why he is in a room with a ‘stranger,’ ” said Joseph Mulhern, in charge of the Fall River, Massachusetts, Youth Advocacy Department of the Committee for Public Council Services, which finds counsel for indigent citizens. In a phone conversation, he told Truthout that he comes to see his child clients in jeans and a T-shirt and tries to meet with families first to get the facts of the case, and then with kids at their house, on a basketball court, or while they play video games. But these tactics do not erase the difficulty for them in comprehending what they need to know, such as “Miranda Rights.”

The Massachusetts Omnibus Juvenile Justice Bill

Changing the system by reworking outdated juvenile law is exactly what Naoka Carey and the Citizens for Juvenile Justice are fighting for. Besides raising the lower age of juvenile culpability from 7 to 11, the proposed bill creates parent-child privilege, decriminalizes school discipline issues and reclassifies offenses to prevent arrests; it “creates a mechanism to promote pre-arraignment diversion and programming in the community” to keep kids from being placed out of their homes; and seeks record expungement of all offenses committed before age 21, “to ensure that a record of an offense committed as a teenager doesn’t act as a lifelong barrier to success.”

As for how many kids would actually be affected if laws were changed, Carey said that in 2012, there were a total of 17,000 complaints alleging that a juvenile was “delinquent” (i.e. capable of forming criminal intent), and those complaints were mostly filed by police or school resource officers. From those complaints, there were almost 500 children arraigned: five of these were 8 years old; 15 were age 9; 20 were 10 years old; 118 were 11 years old; and 325 were age 12, reported Carey.

She said that the most common charge was “assault.” This charge does not necessarily mean anyone was actually injured, because there is quite a wide range of complaints: “Spitting counts as an assault, as well as an actual fight,” said Carey.

Other Solutions

But new laws aren’t the only fix we need to enable us to see, judge and treat kids as kids.

Per Suffolk’s Susan Sered, we need “structural change – to invest in better schools, jobs that pay living wages so people don’t have to be stressed, to clean up the air. … We need to address why the child is doing what she is doing that is deemed problematic. And we need programmatic change.”

From Kaba and VanNatta’s article, such programs might include “education, afterschool programs, sports … camps, and anything that provides young people with resources to learn, grow, develop mastery, meet basic needs, build positive relationships and find ways to share and contribute in their community.” We need to address the racism embedded in education and the services geared toward children.

A police officer in the Desre’e Watson case had the temerity to say, “Do you think this is the first 6-year-old we’ve arrested?” As we move forward – at a time when juvenile crime is at an historic low, according to the National Center for Juvenile Justice – we must think about what answer that question would have in a more humane world.

(Chart: National Center for Juvenile Justice)

(Chart: National Center for Juvenile Justice)

Media that fights fascism

Truthout is funded almost entirely by readers — that’s why we can speak truth to power and cut against the mainstream narrative. But independent journalists at Truthout face mounting political repression under Trump.

We rely on your support to survive McCarthyist censorship. Please make a tax-deductible one-time or monthly donation.