The Miraflores Locks are perhaps the principal tourist attraction of Panama City. Visitors are more than willing to pay the $15 admission to a state-of-the-art museum espousing the grandeur of this enormous emblem of human engineering and its contribution to the global economy.

An exhibit at the West Indian Museum of Panama, residing in an old church, depicts wagons used to move earth during the digging of the Panama Canal. (Photo: Zach Borenstein)

An exhibit at the West Indian Museum of Panama, residing in an old church, depicts wagons used to move earth during the digging of the Panama Canal. (Photo: Zach Borenstein)

The experience culminates on the viewing deck. Hundreds of tourists clamor daily to watch cargo ships pass. So many people fill the deck that it is often difficult to find space to view the spectacle. People are thrilled to see these ships have their altitudes changed by 54 feet over the course of more than 30 minutes.

An exhibit at the West Indian Museum of Panama, residing in an old church, depicts wagons used to move earth during the digging of the Panama Canal. (Photo: Zach Borenstein)

An exhibit at the West Indian Museum of Panama, residing in an old church, depicts wagons used to move earth during the digging of the Panama Canal. (Photo: Zach Borenstein)

And yes, the museum mentions that some people died during the construction of the canal.

A wall with stains and faded paint on the inside of the grounds of the West Indian Museum of Panama. SAMAAP, the Society of Friends of the Museum, feels the Panamanian government has allocated insufficient funds to maintain the museum. (Photo: Zach Borenstein)

A wall with stains and faded paint on the inside of the grounds of the West Indian Museum of Panama. SAMAAP, the Society of Friends of the Museum, feels the Panamanian government has allocated insufficient funds to maintain the museum. (Photo: Zach Borenstein)

There is another museum, though. Right near a central stop on Panama’s new metro, and within walking distance of the frequently visited old town, The West-Indian Museum of Panama has a home.

The grounds belonging to the West Indian Museum of Panama. SAMAAP, the Society of Friends of the Museum, feels the Panamanian government has allocated insufficient funds to maintain the museum. (Photo: Zach Borenstein)

The grounds belonging to the West Indian Museum of Panama. SAMAAP, the Society of Friends of the Museum, feels the Panamanian government has allocated insufficient funds to maintain the museum. (Photo: Zach Borenstein)

In response to complaints that the Panamanian government offered little respect to the legacy of those that came from various Caribbean nations to build the canal, anthropologist Dr. Reina Torres de Araúz created the museum, which opened in 1980. It is a public museum operated by INAC, the National Institute of Culture.

The former church that now houses the West Indian Museum of Panama. Weeds grow at the base of the building, paint is peeling, there is highly evident soot on the walls and rust on the roof. SAMAAP, the Society of Friends of the Museum, feels the Panamanian government has allocated insufficient funds to maintain the museum. (Photo: Zach Borenstein)

The former church that now houses the West Indian Museum of Panama. Weeds grow at the base of the building, paint is peeling, there is highly evident soot on the walls and rust on the roof. SAMAAP, the Society of Friends of the Museum, feels the Panamanian government has allocated insufficient funds to maintain the museum. (Photo: Zach Borenstein)

This museum receives little care from the government. Paint peels from gray walls covered in soot on the exterior of this former humble church. Many homeless people take up shelter beneath the building’s awnings. The museum is staffed largely on the basis of government favors rather than merit, and not one of the six full-time employees is of West-Indian descent.

The entrance to the offices of The West Indian Museum of Panama and SAMAAP, The Society of Friends of the Museum. Paint is fading, the façade is visibly dirty, there is writing on the wall and trash can be seen in the picture. SAMAAP feels the Panamanian government has allocated insufficient funds to maintain the museum. (Photo: Zach Borenstein)

The entrance to the offices of The West Indian Museum of Panama and SAMAAP, The Society of Friends of the Museum. Paint is fading, the façade is visibly dirty, there is writing on the wall and trash can be seen in the picture. SAMAAP feels the Panamanian government has allocated insufficient funds to maintain the museum. (Photo: Zach Borenstein)

Price of admission to this one-room exhibit is a dollar to the general public. It is not uncommon that fewer than five people visit the museum on any given day. Perhaps accustomed to public neglect, members of Panama’s West-Indian community quickly formed a society, SAMAAP (Society of Friends of the West-Indian Museum of Panama) to support the museum. It is easy to imagine that the museum would no longer exist without the support of this private, nonprofit organization. Its members designed the exhibits. The air-conditioning in the office in which the director and two other employees work is paid for by SAMAAP (the other employees are seldom-used guides). A current $28,000 construction project to expand the office is being paid for by SAMAAP.

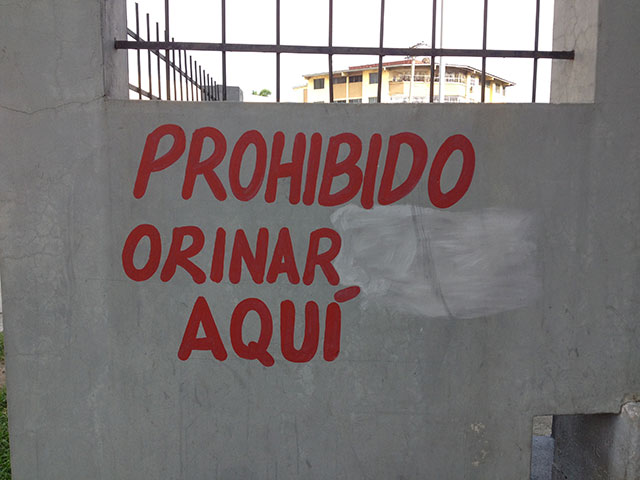

A painted sign outside of The West Indian Museum of Panama reads, “It’s Prohibited To Urinate Here,” referencing problems the museum has had. The state of the walls indicates that a new coat of paint has long been needed. SAMAAP, the Society of Friends of the Museum, feels the Panamanian government has allocated insufficient funds to maintain the museum. (Photo: Zach Borenstein)None of the guides speak English. Many of the countries from which the canal workers came were British colonies. The Canal Zone was occupied by the United States until 2000, and the principal language spoken was English. The first language of many of the families that descended from the original canal workers is still English. And yet their first language is not represented by the museum guides.

A painted sign outside of The West Indian Museum of Panama reads, “It’s Prohibited To Urinate Here,” referencing problems the museum has had. The state of the walls indicates that a new coat of paint has long been needed. SAMAAP, the Society of Friends of the Museum, feels the Panamanian government has allocated insufficient funds to maintain the museum. (Photo: Zach Borenstein)None of the guides speak English. Many of the countries from which the canal workers came were British colonies. The Canal Zone was occupied by the United States until 2000, and the principal language spoken was English. The first language of many of the families that descended from the original canal workers is still English. And yet their first language is not represented by the museum guides.

To say that this is a museum issue would be a selective understanding of the problem. Mainstream Panama society pays little attention to the desires of the Black community. In 1991, anti-crime signs were posted throughout the city, depicting Black caricatures handcuffed by dutiful white cops. Afro Panamanian public figures are frequently mocked by the mainstream television programs. Blackface is still common in the public sphere.

This piggy backs off of historic oppression of people of African descent in Panama. Slavery was a big part of the Spanish colonial system, until independence was gained by the Grand Colombia in 1821.

Panama’s history is heavily linked to the United States. Panama was only able to gain independence from Colombia in 1903, after the US funded a $25 million purchase of that freedom. The US offered these finances in exchange for control in building the canal.

Apartheid policies of the US south were implemented in the Canal Zone. Black workers had to use different entrances to public buildings, were paid roughly half of what white workers made for the same work and their children went to different schools.

Remembering the past, however, is difficult in a country that wants to detach its association from prejudiced policies. This is also a big reason SAMAAP was created. Every year, it organizes a trip to the canal, where members throw rose petals into the water in honor of those that died during the construction.

More than 25,000 people did.

A painted sign outside of The West Indian Museum of Panama reads, “It’s Prohibited To Urinate Here,” referencing problems the museum has had. SAMAAP, the Society of Friends of the Museum, feels the Panamanian government has allocated insufficient funds to maintain the museum. (Photo: Zach Borenstein)

A painted sign outside of The West Indian Museum of Panama reads, “It’s Prohibited To Urinate Here,” referencing problems the museum has had. SAMAAP, the Society of Friends of the Museum, feels the Panamanian government has allocated insufficient funds to maintain the museum. (Photo: Zach Borenstein)

This is more than eight times the number of people that died on September 11, 2001. In New York, the nation’s now tallest building was made to remember the tragedies.

The sign for the entrance to The West Indian Museum of Panama. The edits to the sign have been done such that it is not entirely clear what the numbers read. SAMAAP, the Society of Friends of the Museum, feels the Panamanian government has allocated insufficient funds to maintain the museum. (Photo: Zach Borenstein)

The sign for the entrance to The West Indian Museum of Panama. The edits to the sign have been done such that it is not entirely clear what the numbers read. SAMAAP, the Society of Friends of the Museum, feels the Panamanian government has allocated insufficient funds to maintain the museum. (Photo: Zach Borenstein)

In Panama, tucked away on a street corner in a busy, relatively dangerous neighborhood, an old church has been converted into a museum.

The West Indian Museum of Panama. (Photo: Zach Borenstein)

The West Indian Museum of Panama. (Photo: Zach Borenstein)

Information from this article was taken from The West Indian Museum of Panama; the book People of African Ancestry in Panama 1501-2012, by Melva Lowe de Goodin; conversations with members of SAMAAP and personal observations of Panamanian society.

We have 9 days to raise $50,000 — we’re counting on your support!

For those who care about justice, liberation and even the very survival of our species, we must remember our power to take action.

We won’t pretend it’s the only thing you can or should do, but one small step is to pitch in to support Truthout — as one of the last remaining truly independent, nonprofit, reader-funded news platforms, your gift will help keep the facts flowing freely.