Shadowproof recently revealed that California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) prison officials are once again orchestrating “gladiator fights” at multiple state prisons.

“Gladiator fights” are the institutional practice of pitting known rivals on the prison yard with foreknowledge that they are mandated to fight through their respective gang affiliation. Prison administrators know that certain groups are in conflict and will not associate with one another.

However, sometimes this manufactured animosity does not work. For instance, in August 2012, the leaders of Black, white and Latinx groups from the Pelican Bay Segregated Housing Unit drafted the Agreement to End Hostilities for California’s prisons. The Agreement condemned CDCR’s divide-and-conquer method, successfully cutting in half the amount of violence occurring on prison yards throughout the state.

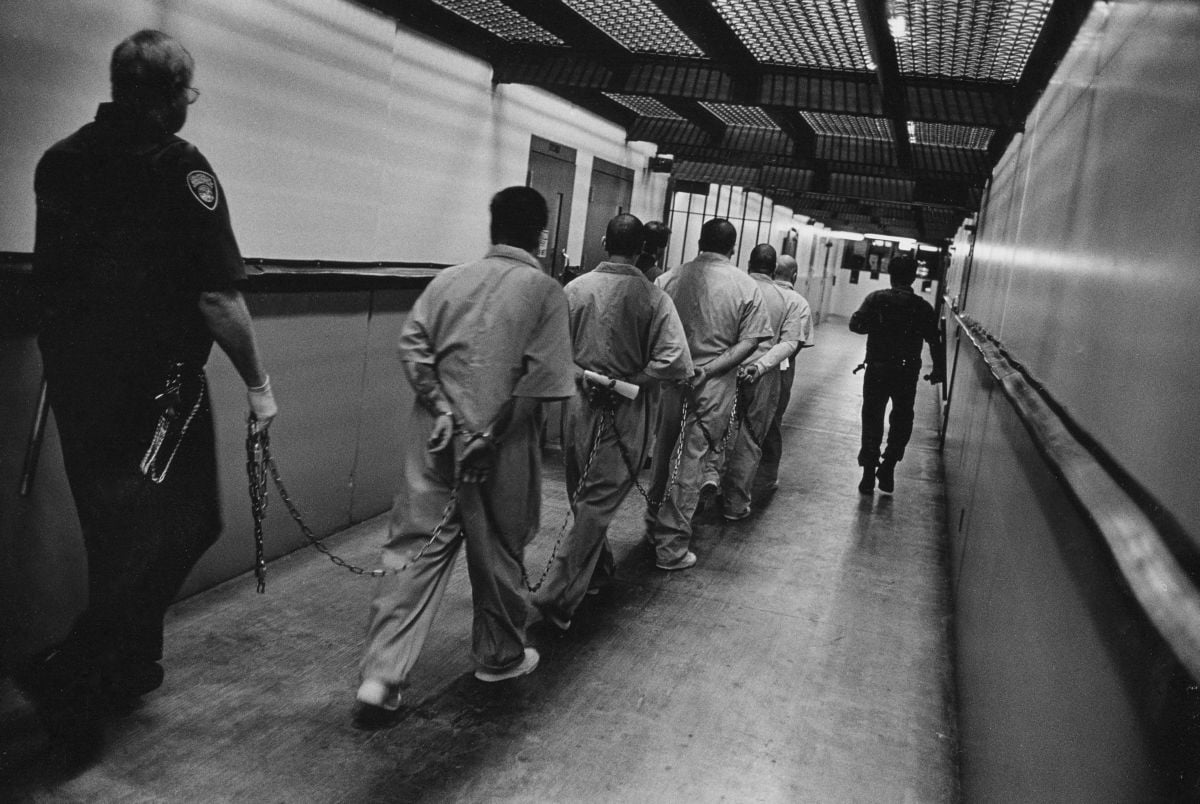

In order to undermine solidarity among prisoners, it is CDCR policy to ignore the Agreement, and under the cynical cover of “desegregating prisons,” to release signatories of the agreement into yards with those who are not, effectively acting in the role of spoiler of the Agreement. This policy is known as “incremental release.” Prisoners are released onto the yard in the CDCR’s full expectation of violence and the potential for great bodily injury. Prisoners are set up to fight in the way that dogs are, and prison guards use pepper spray, block guns (air-powered non-lethal rifles that shoot rectangular immobilizing wooden blocks) or mini-14 rifles with lethal rounds to subdue the predictable outcome.

Due to pressure from supporters and families of incarcerated people, the CDCR, as of September 24, has put the “incremental release” program on a temporary hold for review. Whether this is a public relations move meant to dampen down controversy around the policy, or will lead to its elimination is unclear at this time.

This practice first came to public attention in the 1990s when it was revealed that guards at California’s Corcoran Secure Housing Unit were staging fights between Black and Latinx prisoners for voyeuristic pleasure and gambling on outcomes. In order to terminate the fight, guards fired either block guns or 9-millimeter rounds at prisoners. From 1989 to 1994, seven prisoners were shot dead, and 43 more were injured. After a couple of guards turned into whistleblowers and the story reached national attention, eight Corcoran guards were brought to trial and eventually acquitted in a miscarriage of justice hidden behind “policy.” The attorneys for the “Corcoran 8” argued that in no way could the guards be held responsible for the individual actions of “vile and violent inmates,” namely fighting, and the court agreed. This, despite the fact that guards were purposefully creating conditions which guaranteed this very outcome and then executing them.

Over the last year, dozens of gladiator fights have been orchestrated by the CDCR across a variety of institutions, namely the California State Prison in Corcoran, the Correctional Training Facility in Soledad, Pleasant Valley State Prison, and others.

Video taken by prisoners through a contraband cellphone and published by Shadowproof captures CDCR’s gladiator fighting of prisoners on February 14 and 15 in Soledad.

Most recently, on August 13, the head of CDCR, Secretary Ralph Diaz, visited the Soledad prison. During his visit, prisoners pleaded for an end to the practice of incremental release, but Secretary Diaz has adamantly refused to review or eliminate the policy.

After an incremental release the very next day, a massive riot broke out between rivals involving around 200 people; eight were hospitalized and an additional 50 were injured.

Prison Gangs as Survival Strategy

One of the ways the CDCR deploys its brutal power is by indirectly deputizing prisoners to do violence on the institution’s behalf. It establishes initial conditions of scarcity that guarantee the emergence of violence among the population it quarantines, and then steers that violence for the purpose of maintaining control of the prison population. The prison is a closed system, stabilized by gun towers, and custodial administration regulates essential resources.

Prison is an amortized starvation program. Prisoners lack warm clothing in the winter, or suffer mind-numbing heat in the summer. Many of California’s prisons are in the state’s most inhospitable climes: concrete walls freeze like ice cubes; they also literally sweat. Prisoners lack toothpaste and toilet paper, and are totally dependent on the uninterested (if not outright hostile) jailer to hand them over. The imposed scarcity on the prison yard is psychologically and materially unsustainable. Within this condition of imposed scarcity, prisoners band together to increase their chances of survival: These are prison gangs.

The prison is a strange phenomenon, for it is effectively a concentrating of the most traumatized populations within the United States — the poor, the racially marginalized, those with mental illness or addiction — and subjecting them to conditions of imposed scarcity within a violently controlled space. Society suspends all we know about trauma and its effects, and replaces it with a medieval conception of punishment and re-traumatization — and then disavows the outcome.

CDCR’s argument is that prisoners should effectively “program,” or accept their conditions, and do nothing to remediate their torture. There is a contradiction in what the CDCR is asking: for individuals to self-efface. The “model prisoner” by CDCR standards would have to exist in violation of all instincts toward self-preservation. The model prisoner is, in fact, suicidal. Prisoners know this, and resist.

CDCR then further criminalizes the psychological and material resistance to these very conditions of imposed scarcity — starvation, natal alienation, exposure to random brutality and humiliation.

When the U.S. sends Black and Brown people into prison in disproportionate numbers, this is what we are doing to them. We are imposing conditions of scarcity and starvation, fighting them like animals and further criminalizing human beings attempting to survive and maintain dignity.

In this process, a new being emerges within neoliberal discourses of personal responsibility that utterly elide the material and ideological embeddedness of those targeted by and within the carceral system.

Reinforcing the Prison Construct

The prison is a proto-genocidal machine bent on the disappearance and liquidation of the largely racialized and urban subproletariat in order to scrub the social field of “excess” human beings within the framework of organized neoliberal capitalism.

The truth of this shocks the conscience, and for this reason, is intolerable and rendered invisible. An ideological architecture must be developed in order to justify this brutal and murderous operation. Neoliberal narratives of individual responsibility and bad choices do some of the work, but in order to justify the machine-like brutality of the prison apparatus, additional ideological work is needed.

This is where gladiator fights come in. By continually creating conditions that guarantee the emergent organization of prison gangs in order to escape psychological and material scarcity, the prison guarantees competitive violence over scarce resources.

When these groups engage in a struggle in order to survive — steal, fight, develop black market economies — the CDCR, and by extension the state itself, wipes its hands of creating the conditions by which violence is made to occur, then subdues, categorizes and disciplines the individuals engaging in such strategies.

Moreover, the state continually reproduces crises, like staging gladiator fights, that it itself intervenes upon in order to make itself appear necessary. Administrators fight prisoners like dogs to show them as animals, but they create conditions by which prisoners have to fight, and then say it was the prisoners’ choice.

The ideological operation of the carceral system magically transforms human beings, and society sees itself as justified in putting people in prison. The cause and effect are literally inverted. Gladiator fights produced within the prison attempt to justify the existence of the prison itself. The carceral system ideologically obfuscates its own role in the creation of conditions of precarity on the meta scale. At the individual level, it continually produces a racialized “other” — the “prison gangster” — as the target of its operation.

That’s why gladiator fights have returned. They are the exemplary technology and modality of the logic of carceral social control:

- Criminalize racialized and superfluous labor;

- Concentrate them and impose scarcity;

- Further criminalize their survival strategies, and steer them for the purposes of institutional control;

- Dehumanize the targets of this operation.

Gladiator fights produced within the prison justify the existence of the prison itself, and the prison is what makes neoliberal capital possible, at all.

Truthout Is Preparing to Meet Trump’s Agenda With Resistance at Every Turn

Dear Truthout Community,

If you feel rage, despondency, confusion and deep fear today, you are not alone. We’re feeling it too. We are heartsick. Facing down Trump’s fascist agenda, we are desperately worried about the most vulnerable people among us, including our loved ones and everyone in the Truthout community, and our minds are racing a million miles a minute to try to map out all that needs to be done.

We must give ourselves space to grieve and feel our fear, feel our rage, and keep in the forefront of our mind the stark truth that millions of real human lives are on the line. And simultaneously, we’ve got to get to work, take stock of our resources, and prepare to throw ourselves full force into the movement.

Journalism is a linchpin of that movement. Even as we are reeling, we’re summoning up all the energy we can to face down what’s coming, because we know that one of the sharpest weapons against fascism is publishing the truth.

There are many terrifying planks to the Trump agenda, and we plan to devote ourselves to reporting thoroughly on each one and, crucially, covering the movements resisting them. We also recognize that Trump is a dire threat to journalism itself, and that we must take this seriously from the outset.

Last week, the four of us sat down to have some hard but necessary conversations about Truthout under a Trump presidency. How would we defend our publication from an avalanche of far right lawsuits that seek to bankrupt us? How would we keep our reporters safe if they need to cover outbreaks of political violence, or if they are targeted by authorities? How will we urgently produce the practical analysis, tools and movement coverage that you need right now — breaking through our normal routines to meet a terrifying moment in ways that best serve you?

It will be a tough, scary four years to produce social justice-driven journalism. We need to deliver news, strategy, liberatory ideas, tools and movement-sparking solutions with a force that we never have had to before. And at the same time, we desperately need to protect our ability to do so.

We know this is such a painful moment and donations may understandably be the last thing on your mind. But we must ask for your support, which is needed in a new and urgent way.

We promise we will kick into an even higher gear to give you truthful news that cuts against the disinformation and vitriol and hate and violence. We promise to publish analyses that will serve the needs of the movements we all rely on to survive the next four years, and even build for the future. We promise to be responsive, to recognize you as members of our community with a vital stake and voice in this work.

Please dig deep if you can, but a donation of any amount will be a truly meaningful and tangible action in this cataclysmic historical moment.

We’re with you. Let’s do all we can to move forward together.

With love, rage, and solidarity,

Maya, Negin, Saima, and Ziggy