Before dawn on March 4, 2024, a car painted with birch trees crept out onto a narrow dirt road granting Mountain Valley Pipeline construction workers access to the site. Two activists, 81-year-old River and 63-year-old Andy, unfurled a large banner reading “Older Than the Hills: Water is Life” and covered the rear of the car. The two — who asked to be identified only by their first names to protect them from reprisal — sat down, reached through specially drilled holes in the car, and locked themselves in for the long haul. Hours later, pipeline contractors attempting to drive to work found themselves stymied by the protest and called in the Virginia State Police — again. It took over 10 hours for police to extract Andy, during which time construction ground to a halt.

Andy and River’s direct action against the pipeline was one part of a broader day of protest held on Poor Mountain, one of the last sections of construction still uncompleted. This section of the pipeline construction is among the steepest and most treacherous, labeled by the Securities and Exchange Commission a “challenging physical construction condition.” A pipeline employee has been injured there, and as construction continues, activists’ warnings are coming to pass: The clearcutting of sections of forest to dig the pipeline trench has already sent plumes of sediment hurtling into the watershed below. The steepest sections of the pipeline are the most dangerous, and they are the sections where activists focused their attention on March 4.

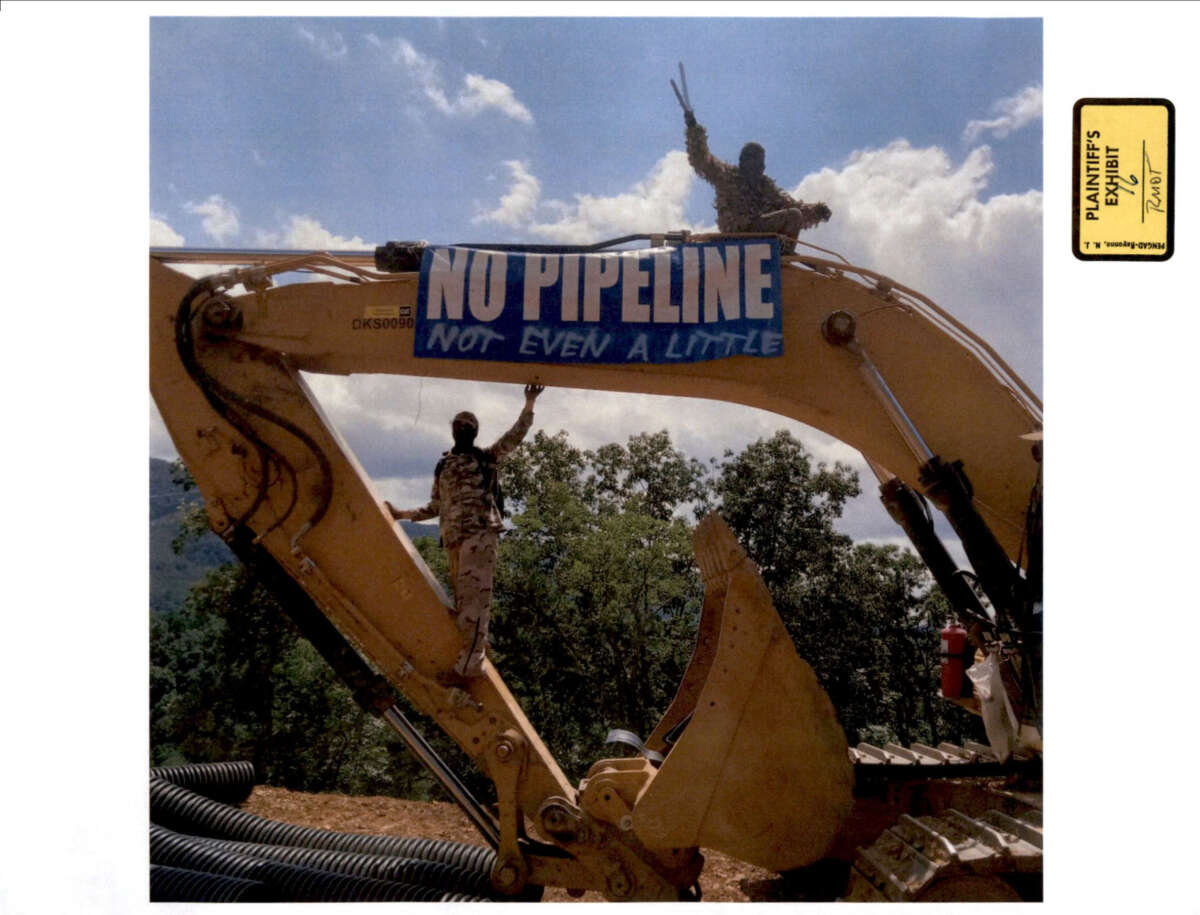

Other protesters clad in camouflage snuck behind the vehicle blockade onto the construction site, where they slung a large banner reading “Defend the Forest Everywhere” between two bulldozers. Another 15 people rallied on the roadside, providing support and encouragement to Andy and River. It’s been a long fight, but for many activists, it’s not an optional one. Landowners impacted by the pipeline, Appalachian environmentalists and neighbors of the pipeline keep turning out to buy one more day against the pipeline’s slow march.

If completed, the Mountain Valley Pipeline would traffic natural gas 303 miles from fields located in northern West Virginia down to an existing pipeline in southern Virginia. The route covers hundreds of miles of ecologically sensitive land, snaking under the Blue Ridge parkway, running through expanses of national forest, and crossing under a section of the Appalachian Trail.

Given the crisscrossing jurisdictions involved, the pipeline has faced permitting legal challenges with the Fish and Wildlife Service, Army Corps of Engineers, the U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management. In a deluge of lawsuits over permitting, it emerged that, by April 2023, Mountain Valley Pipeline had violated its construction permit 139 times. With the pipeline already six years delayed, opponents of the project hoped for perennial legal limbo to delay the project into oblivion. In 2023, however, Congress made a pork-barrel deal to fast-track the pipeline in exchange for West Virginian votes for a debt ceiling bill.

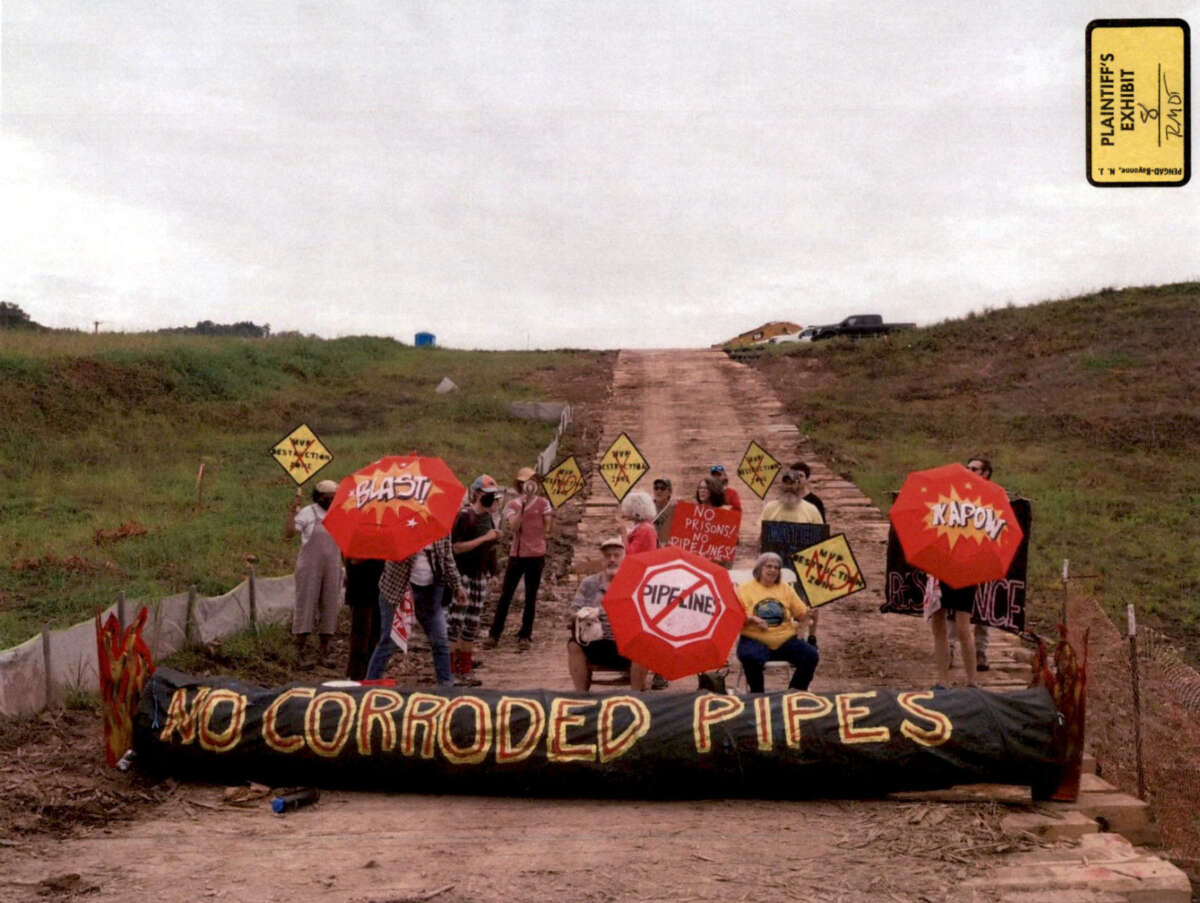

A vigorous protest movement has fought the project at every step of the pipeline’s plodding path, and they aren’t giving up now. In 2021, a rotating contingent of protesters successfully blockaded part of the pipeline for 932 days — over two and a half years. Like clockwork, every two weeks or so, dissenters against the pipeline project trek out onto the construction site land, often prepared to engage in meticulously planned civil disobedience actions using “sleeping dragons” — jerry-rigged PVC contraptions often reinforced with wire, concrete, rebar or tape that protesters use to handcuff themselves together in an immovable line. Extracting protesters who have handcuffed themselves inside sleeping dragons often demands hours of law enforcement’s time. Protesters say every hour of delay incrementally increases the pipeline’s cost and further delays construction.

Maggie, an Appalachians Against Pipelines protester involved in the movement for several years who asked to be identified using a pseudonym in the face of state repression, said the protest movement centers direct action “because the other tactics have a different timeline.”

Environmentalist groups, including the Sierra Club and Wilderness Society, have sued the pipeline over permitting issues, including challenges over whether the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service issued a permit that violated Endangered Species Act protections for two endangered species of fish: the Roanoke logperch and the candy darter.

Six Virginia property owners whose land was taken under eminent domain also sued over the question of whether the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission could legally seize land on behalf of a for-profit entity. Both cases recently hit walls in the courts. Sen. Joe Manchin’s debt ceiling deal melted away other pending suits, clearing the path for the Mountain Valley Pipeline.

“In different avenues people have been fighting eminent domain and permitting, trying to contact their representatives,” Maggie said. “But at this point, a lot of those good alternatives have been closed off. And what we’re left with is direct action.”

Protest as… Kidnapping?

In October, Maggie rallied on an ATV access road just off of the pipeline construction site. She and other members of the support rally knew that in resisting the pipeline, there is no such thing as a safe protest. She braced for the possibility of picking up misdemeanor trespassing charges, or perhaps disorderly conduct or failure to disperse. What she hadn’t expected was a felony — and a bizarre felony at that. Weeks after police identified Maggie at the support rally, they served a warrant at her house informing her that she’d been charged with felony abduction, or — for those less versed in legal jargon — kidnapping.

Virginia’s statute defines kidnapping as using force, intimidation or deception to transport or detain another person. It’s clearly a kidnapping offense to stuff someone in your trunk or trap them in your basement. But in the likely event that you’re confused by how a protester can be charged with kidnapping, here’s how the state’s logic goes: The support rally protesters blocked the pathway of a vehicle, making the driver unable to leave, so under the law, he was detained, ergo “kidnapped.” (Giles County prosecutors, who brought the charge against her, can’t be keen to discuss the fact that the driver was able to walk away from the equipment at any time.)

It’s an absurd charge, and one that protesters hope a judge will view with skepticism. But in the meantime, the charges tie up activists in a protracted legal battle. When Maggie turned herself in on the felony abduction charges, she was arrested and processed through the Western Virginia Regional Jail. The solidarity networks of activists bailed Maggie out, but being out on bail comes with a series of bond conditions attached. It’s all part of a broader strategy to keep protesters out of the movement.

“If I get arrested for anything, even a traffic stop, the charges will show up,” Maggie said. “It’s just a way to keep us scared and compliant.”

Escalatory Tactics Against Protesters

The decision Virginia and West Virginia made to classify what might otherwise be misdemeanor trespassing as felony abduction (and in other cases, felony theft), escalates repressive tactics against protesters. This intimidation tactic — called “upcharging” — isn’t unusual, and falls in line with a broader trend of police and prosecutors pursuing ever more egregious prosecutions. In response to the 2016 Dakota Access Pipeline protests, state legislatures across the country passed bills increasing the penalties for protest of “critical infrastructure,” which is defined to include pipelines. As of 2022, at least 17 states passed critical infrastructure bills increasing the penalties for impeding pipeline construction or obstructing access to construction sites. In 2020, West Virginia imposed felony charges for pipeline protesters and added conspiracy liability for anyone aiding protesters. That latter provision raises the possibility of criminalizing bail funds, a tactic Georgia prosecutors have taken to an extreme in the Stop Cop City RICO case. (Thus far, Virginia has no critical infrastructure anti-protest statute, explaining the innovative use of felony abduction charges.)

There are early hints of even more menacing charges on the horizon. A climate scientist protesting the Mountain Valley Pipeline last September said West Virginia police threatened protesters with domestic terrorism charges. Those cops went out over their skis on the current state of the law, but the West Virginia legislature is considering a bill this session that could expand the definition of terrorism to encompass pipeline protests, including protests that block roads but do not directly interfere with construction equipment.

Environmental protesters have long been the victims of state conflation of activism with terrorism. Throughout the 1990s, the FBI extensively surveilled environmental activists, and in 2005 cited the Animal Liberation Front and Earth Liberation Front as two of the greatest domestic terrorism threats facing the nation. On the animal rights side, Congress passed legislation under which activists who ran a website that encouraged direct action were prosecuted for terrorism. But in recent years, investigation of environmental protest through the prism of terrorism has collided with a rise in attention to critical infrastructure, as defined in the Patriot Act as the national assets, public and private, for which any damage could harm the United States. In the eyes of the government, pipelines are too important to fail.

That’s why Virginia and West Virginia have deployed so many resources, prosecutorial and political, to repress pipeline protest. From Manchin’s debt ceiling deal to charging protesters with felony abduction, the states fight for the pipeline like their economy depends on it. For protesters, another world is possible. Not so for pipeline companies and their political allies.

Protesters Won’t Be Intimidated

For years now, protesters have returned again and again to the Mountain Valley Pipeline. Everyone in the movement understands the risks. Protesters locking down construction equipment do so with the knowledge of impending criminal charges. Grandmothers show up in rocking chairs to block roadways in support of the blockades and lockdowns, even though they might face trespassing charges. Even people rallying on public roadsides understand police harassment to be a possibility. On September 5 of last year, police cited people participating in a roadside rally for improper stopping on the highway, failure to possess a driver’s license and improper parking. Anyone protesting the pipeline, whether in Appalachia or in solidarity actions across the country, understands the risk of inaction far outweighs the cost of protest, however high the state tries to make that cost.

“It’s not really a question of if the pipeline fails, it’s a matter of when,” said Maggie, who, before joining the protest movement in Appalachia, took notes from the Dakota Access Pipeline and other pipeline resistance movements that have occurred since then. So long as the pipeline continues its slow march across Appalachia, protesters will meet it.

If completed, the pipeline will transport liquified natural gas (LNG) across Appalachian wilderness, traversing steep terrain that increases the risk of leaks for the pressurized pipeline. And while some studies suggest that LNG is cleaner than coal, other data indicate that methane flares and leaks substantially reduce any benefit relative to coal. What’s undisputed is that LNG is a major fossil fuel contributor to greenhouse gas emissions, and that the completion of the pipeline would lock in reliance on natural gas rather than renewable alternatives. For a lot of protesters, resistance is a matter of necessity.

At one of the actions, a pipeline private security officer yelled in frustration about police who let some protesters walk away without arrest. “So what about tomorrow? Because these people will be back here tomorrow, and the next day, and the next day. They don’t get the point.”

Protesters from Appalachians Against Pipelines have appropriated the security officer’s cry of frustration and turned into their own rallying call to action. “Tomorrow and the next day and the next day,” they posted on social media, followed by a link inviting others to join the protest. They’ll be back.

We have 2 days to raise $31,000 — we’re counting on your support!

For those who care about justice, liberation and even the very survival of our species, we must remember our power to take action.

We won’t pretend it’s the only thing you can or should do, but one small step is to pitch in to support Truthout — as one of the last remaining truly independent, nonprofit, reader-funded news platforms, your gift will help keep the facts flowing freely.