Part of the Series

Planet or Profit

Did you know that Truthout is a nonprofit and independently funded by readers like you? If you value what we do, please support our work with a donation.

Sao Paolo and Brasilia, Brazil — Warwick Manfrinato, the director of Brazil’s Department of Protected Areas, has a deep understanding of biological interdependence, as well as its importance.

“If we are of utter service to nature, then we provide the benefits to all other living things on the planet,” Manfrinato told Truthout in his office at Brazil’s capital city recently. “I have the same value as a human as a jaguar has in nature, and both should be protected, otherwise we all go extinct, no matter what.”

Manfrinato, whose department falls within the Secretariat of Biodiversity in Brazil’s Ministry of Environment, is working on a variety of projects, including the establishment of a whale sanctuary that will cover the better part of the entire South Atlantic Ocean between Brazil’s vast coastal area all the way across to the west coast of Africa. And on June 23, he and his colleagues launched a national “Corridors Program,” with the goal of fostering “connectivity and genetic flux.”

To see more stories like this, visit “Planet or Profit?”

“We know the flow of genetics in biomes [biological systems] in life is critical,” Manfrinato said. “We have to re-establish this, so a jaguar that exists in Mexico should be able to come all the way here without being killed. Physical connectivity allows for genetic connectivity. A monkey should be able to travel from one part of Brazil to another, without having to pass through land that has been cleared, where there is no forest.”

Manfrinato’s colleague, Everton Lucero, who is Brazil’s secretary for Climate Change and Environmental Quality, was blunt with Truthout about what could happen if dramatic action is not taken to address the impacts of anthropogenic climate disruption (ACD).

“The worst-case IPCC [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change projection] is 4.5C by 2100, but at local levels here we see very different impacts already, and are already even seeing an 8C increase in places,” Lucero told Truthout.

Manfrinato echoes this: The crisis, he says, has already arrived.

“Everything that is bad has already happened,” he explained. “We’ve come to terms with who we are, and we are those who destroy the planet. We’ve already destroyed it.”

Because of this, Manfrinato believes we already know what needs to be done.

“If we’re going to look for solutions, we have to look for the solution for the complexity, not one individual thing,” he said. “If there is no connectivity, there is nothing. And that is why I’m busy with building corridors of biodiversity.”

He has his work cut out for him. But he’s not alone: Many people are working toward similar goals in the Amazon.

A Giant Water Pump

In order to get a sense of the connections between Amazon protection and water issues, Truthout met with Fabio Eno, the coordinator for the Natural Sciences Unit of UNESCO in Brazil, in his office in the capital.

Fabio Eno, coordinator of UNESCO’s Natural Sciences Sector for Brazil, links water storage during Brazil’s drought to one of the contributing factors of the Zika virus. (Photo Dahr Jamail)

Fabio Eno, coordinator of UNESCO’s Natural Sciences Sector for Brazil, links water storage during Brazil’s drought to one of the contributing factors of the Zika virus. (Photo Dahr Jamail)

Eno thinks it is more than timely that Brazil happens to be hosting the World Water Forum in March 2018.

“Water and drought are critical issues here now, which is so ironic since Brazil is hosting this huge event on water next year, and we are facing water crisis in some of the largest cities here,” Eno told Truthout. “What we are seeing in Brazil is that climate change has been and continues to be very clearly visible.”

He pointed out that in Brasilia, where there used to be very clearly demarcated dry and rainy seasons, they are now imbalanced: The dry season is starting earlier, and there is less rain during the rainy season. This is a reflection of the progression of climate-related changes in the country.

“In the south, well known for rice production, which has high water consumption, they are facing more droughts and this is affecting local farmers,” Eno explained. “States in the northeast are now more intensely affected by the dry season, so we see clearly the effects of climate change in all portions of Brazil.”

Eno noted that the impacts have been so intense that Brazil has been caught unprepared, and sees this shift in climate as having contributed to a major international health crisis: Zika virus.

“With the major drought recently in Sao Paolo, people were encouraged to store water in basins in their residence, and even in their toilets,” he said. “Then, not coincidentally, we have Zika virus outbreaks that came about the same year Sao Paolo was storing so much more water. People were storing water in every way they could after what happened, but weren’t taking necessary care for safeguards. This caused a major international health issue.”

Manfrinato sees water-related problems as the biggest climate disruption impacts humans have had.

“What differentiates this planet from every other planet is liquid water,” he explained. “It has taken Earth millions of years to find the right balance of liquid water, and people don’t understand how important that is and are messing it up with their greed and ambition, of which awareness is far more important.”

Manfrinato explains that as humans have “fooled around” with temperature, they have shaken the very foundation of biology.

“Fooling around with water is impossible, as that is the tree of the fruit of life,” Manfrinato said. “You mess with it, you mess with everything … and we’ve already messed with it.”

Brazil’s Secretary for Climate Change and Environmental Quality, Everton Lucero, is working to prevent the doomsday scenario of climate disruption compromising the “entire forest” of the Amazon. (Photo: Dahr Jamail)

Brazil’s Secretary for Climate Change and Environmental Quality, Everton Lucero, is working to prevent the doomsday scenario of climate disruption compromising the “entire forest” of the Amazon. (Photo: Dahr Jamail)

Lucero also underscored the Amazon’s critical role in the watery realms, especially regionally. The rainforest, he said, provides “flying rivers” — massive amounts of air-borne moisture that develop above the canopy and move with the clouds and rainfall patterns across South America.

“If you remove the forest, you will cause extreme drought in other regions,” he told Truthout.

But he says that biodiversity is the Amazon’s biggest contribution to the world — and is the most important reason to care for the rainforest.

“The forest itself is suffering from climate change, as are other biomes,” he said. “Variability of climate is affecting the forest from increasing flooding and wildfires, which may, in a doomsday scenario, compromise the entire forest.”

Manfrinato sees humans as part of the ecosystem, and an integral part at that, but most assuredly not the apex.

“What is required is a shift of awareness of our being part of nature,” he said. “The apex is the complexity. Humans are not the apex, and the awareness that comes from this is how dynamic the system is that allows for all of life on Earth…. It’ll do this as long as we allow it to do so.”

Manfrinato is deeply passionate about his work, and in the discussion, sounds as much like a philosopher for the planet as Brazil’s director of protected areas.

“We need to respect complexity in order to survive as a species,” he said. “Everybody and everything wins, or everybody and everything loses if we hold onto this lack of awareness that the complexity is the most important thing. Your apex contribution is to be aware of the complexity, and then to protect it.”

Brazil’s Forest Code

Many people are acutely aware that there is a massive problem with deforestation in the Amazon. Beginning in 2004, however, deforestation started to decline in the Amazon, primarily because of better protection policies in Brazil. However, the last two years have seen a dramatic increase again. Brazil’s government has been in crisis, and monitoring and enforcement have been stymied, allowing for a resurgence.

Fabio Feldmann served in Brazil’s parliament for 12 years in the 1980s and 1990s. He is famous for helping to bring positive changes to the forest code — protections for the Amazon — into Brazil’s constitution in 1988.

“The single most important issue facing Brazil is protecting all of the critical biomes,” Feldmann told Truthout during an interview at his home in Sao Paolo. “If you destroy the Amazon region in Peru, you have a great impact in Brazil, and vice versa.”

He explained that there is currently only weak collaboration between the countries in South America regarding the Amazon, and this is a problem.

“When I was elected, there was a radical change [in consciousness] about environmental areas,” he said. “But this design has not been translated into effective public policies, so now our generation must reflect about what our legacy is to be because right now the deforestation rates in the Amazon are unbelievably high, after so many years.”

Feldmann said he is optimistic, and cites heightened public awareness about the land today as compared to 30 years ago. However, he asked, “Do we have time to do what must be done?”

Clayton Lino is president of the Biosphere Reserve Association of Brazil and is a member of the advisory committee for UNESCO’s Atlantic Forest Biosphere Reserve. Truthout interviewed him at his office in the Biosphere Reserve of the Mata Atlantica rainforest in Sao Paolo, a beautifully forested island in the middle of the sprawling polluted city.

On Brazil’s advisory committee for UNESCO’s Biosphere Reserves, Clayton Lino is working to preserve Brazil’s second largest rainforest, the Mata Atlantica. (Photo: Dahr Jamail)

On Brazil’s advisory committee for UNESCO’s Biosphere Reserves, Clayton Lino is working to preserve Brazil’s second largest rainforest, the Mata Atlantica. (Photo: Dahr Jamail)

“We are under attack daily, because we have laws in the process of being made that destroy other laws that were there to protect the land,” Lino said.

This is important to understand, Lino said, because there is so much international pressure on the Brazilian government to continue deforesting. Cattle ranching accounts for roughly 70 percent of the total deforestation in Brazil, and the demand for Brazilian beef in the US and Europe is driving that ranching.

“While local NGOs are working to protect the Amazon and the Mata Atlantica, we do not see any light now,” he explained. “There is no international help, and the culture of corruption has infected many Brazilians now because corruption has come from the top down, so more and more people are starting to not respect basic laws.”

He is so concerned because his beloved Mata Atlantica, the second biggest rainforest reserve in Brazil, is the most threatened area of rainforest in the world, second only to the Madagascar rainforest.

“We have more biodiversity here than even in the Amazon,” he said while pointing out the window. “The Amazon is far bigger, but in the Mata … we have more endemism [species that live only in one area] than anywhere else in the world.”

Lino explained that fragmentation (isolating sections of the forest) is the primary problem in the Mata.

“There is high biodiversity and fragility, because if you destroy something in one place, it cannot come back in another area of the Mata,” he said. “So, fragmenting it causes a very big problem.”

Today, only 8 percent of the Mata Atlantica remains.

Caring as Protecting

“Without connectivity for evolutionary movement, it cannot proceed,” Manfrinato explained of the natural corridors he is striving to create across his country. “This adaptation process needs north/south corridors, because species in the southern hemisphere need to migrate south, and in the north, they’ll need to migrate northwards as global temperatures continue to increase.”

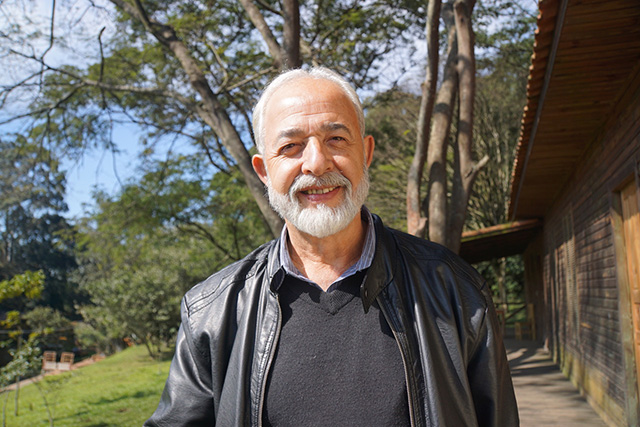

Warwick Manfrinato, Director of Brazil’s Department of Protected Areas, is working to reconnect all of the biodiversity corridors across the Amazon. (Photo: Dahr Jamail)

Warwick Manfrinato, Director of Brazil’s Department of Protected Areas, is working to reconnect all of the biodiversity corridors across the Amazon. (Photo: Dahr Jamail)

Previous to his current job, Manfrinato was a member of the University of Sao Paolo’s Amazon research group, which bore the idea of ecological corridors. This is why he was given the position he has in the government: to implement these ideas on the ground.

“Protection is connection, and vice versa; it has to be both,” he said.

Claudio Angelo is the head of communications for Climate Observatory, an NGO. A former journalist, he now runs a news website for a vast network of 41 Brazilian NGOs which produces annual estimates of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Claudio Angelo is the communications head for Brazil’s Climate Observatory, a network of 41 Brazilian NGOs. (Photo: Dahr Jamail)

Claudio Angelo is the communications head for Brazil’s Climate Observatory, a network of 41 Brazilian NGOs. (Photo: Dahr Jamail)

Angelo explained to Truthout that observable shifts in rainfall patterns are now becoming common across the country, along with a shifting of the timings of the wet and dry seasons. Plus, like much of the world, Brazil is seeing far higher temperatures than ever before. He points to some farming regions that have already seen 6C increases.

“Brazil has warmed faster than the global average, since we are in the tropics,” Angelo said. “Since 1961, it is 1C hotter in Brazil, and it took us half the time to warm the same as the rest of the world.”

Angelo noted that the Amazon has seen two 100-year drought events (extreme drought events that only happen every 100 years) in a five-year period — the first in 2005 and then another in 2010.

“The feedback mechanisms that exist between deforestation and climate change are my biggest concerns,” he said. “Deforestation was 46 percent of our emissions last year, so our main focus is on mitigation. Hence, we are advocating for zero deforestation in Brazil.”

Like Feldmann, Angelo had grown hopeful that his country was finally getting the deforestation of the Amazon under control, until recently.

“Over the last two years we saw this not to be the case, as we had a 60 percent increase in deforestation in just the last two years,” he said. “Because of this, Brazil ranks in the top 10 [countries, in terms of] global greenhouse gas emissions.”

When trees are chopped down, all the CO2 they sequestered from the atmosphere is released. Angelo pointed out the window and discussed the obvious changes.

“Brazil is still water rationing as we speak, after two record-drought years in a row,” he explained. “2015 saw a 45-day heat wave. There is no way you can take off a huge chunk of some part of the planet and think it won’t have a major impact on climate change.”

As a climate journalist Angelo has reported from the Arctic, Greenland, Antarctica and deep into the Amazon. But right now, he is most struck by what he is seeing in his hometown of Brasilia. When he was a child, he remembers how cold it was in the evenings during the winter, and how summers were not as hot as they are now.

“The number of warm nights, when it is not below 20C, has increased 10 times more than it was 30 years ago,” he lamented. “Most of the year here now it’s just nasty. It’s just hot, and it wasn’t like this 20-30 years ago.”

Personal experience plays a core role in Manfrinato’s motivations, as well. He shared his experience from a recent long hike he’d taken that had a deep effect on his perception of the planet.

“It was in a newly protected area of Brazil and I came out of there feeling part of that place, meaning, that place is mine, and I’m going to protect it,” he explained. “And so, we need everyone to start feeling that way about places … about the planet. You belong to it because it belongs to you. You don’t protect it because it belongs to everybody, you protect it because it belongs to you. The land belongs to me, because I belong to the land.”

Manfrinato continues his work to reconnect wildlife habitat on the local levels. He aims to move it from local to regional connections, then regional to national, then across borders, then continental.

“We are promoting this internationally,” Manfrinato said. “Because without reconnection, we will not survive.”

Media that fights fascism

Truthout is funded almost entirely by readers — that’s why we can speak truth to power and cut against the mainstream narrative. But independent journalists at Truthout face mounting political repression under Trump.

We rely on your support to survive McCarthyist censorship. Please make a tax-deductible one-time or monthly donation.