Chicago is the economic core of the vast hinterland that spans the United States Midwest called the Rustbelt. Unlike other major Rustbelt cities like Baltimore and Detroit, on the surface Chicago seems to have weathered the industrial decline that gave the region its nickname. Yet a closer look at the city reveals an uneven pattern of capitalist development: decades of state and private investment have developed downtown Chicago for the well-to-do, while poor Black and Brown working-class neighborhoods on the West and South Sides have been completely neglected and abandoned.

This pattern can be traced to the city’s deep history of racial segregation. In fact, Chicago’s rise as an industrial metropolis in the 19th century rested on the exploitation of immigrant and Black labor, as well as the enduring color line that was reinforced on the factory floors and in the neighborhood streets. Then and now, this geography of inequality that shapes Chicago neighborhoods does not make national headlines. Instead of the decades-long history of racial segregation and contemporary policies of state abandonment that fuel the hardships of South Side residents, the focus remains on depoliticized understandings of crime and youth violence.

In recent years, important scholarship and activism has challenged the constant hand-wringing about youth violence by pointing to the longstanding systemic inequalities and the policies that continue to reinforce youth marginality. One of these critical voices is that of Professor Lance Williams, the son of a former Vice Lord gang member and a professor at the Jacob H. Carruthers Center for Inner City Studies at Northeastern Illinois University. Since the 1980s, Williams has worked closely with South Side youth in different capacities — as a mentor, an educator, an advocate and activist. As a scholar, Professor Williams remains deeply committed to documenting the history of Chicago from the perspective of its most vulnerable and marginalized residents: street-involved Black youth. He has written two separate books that explore the social histories of Chicago’s two most important and rival Black street organizations: the Black P. Stones and the Gangster Disciples.

In his first book, co-authored with Chicago journalist Natalie Y. Moore, Williams explores the evolution of the Almighty Stone Nation gang, placing them in the context of changing economic, social and political Black life in the Woodlawn neighborhood in the early 1960s, tracing their rise and popularity among disadvantaged Black youth, their politicization by the Black Power era and the attempts of the federal government to discredit them by indicting them on domestic terrorism charges.

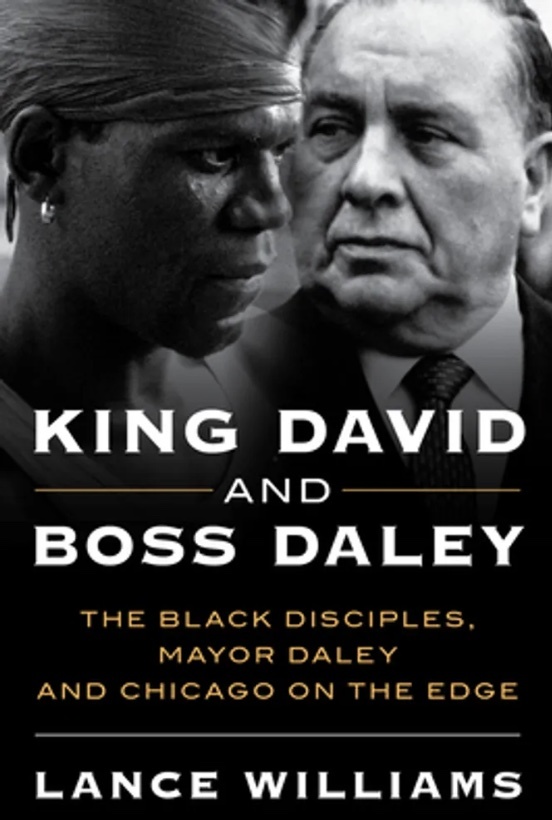

Williams’s interests and community work with gang-affiliated Black youth led him to write a second book, which explores the parallel stories and lives of two of the most powerful South Side Chicagoans, “Boss” Mayor Richard J. Daley and “King” David Barksdale, to explore the tensions between, as he puts it, “the Black inner city and City Hall.” In this most recent book, titled King David and Boss Daley: The Black Disciples, Mayor Daley and Chicago on the Edge, Williams weaves personal experiences, firsthand accounts and interviews, and archival documents and history to reconstruct the lives of two powerful men, the historical moment that produced them, and their political trajectories and influence on Chicago politics. It is a book that is at once a biography of two powerful historical figures, a history of race relations in 20th-century Chicago, and a deep dive into the lives and struggles of a generation of Black youth who were trying to be understood and heard in a world that marginalized, dehumanized and feared them.

I recently met up with Williams in his office at the Carruthers Center for Inner City Studies, where he has been teaching for the last 25 years. We talked about the book, the importance of writing history for and from the perspective of those on the margins, and fighting against the policies that continue to reinforce youth marginalization and violence. The following transcript has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Zhandarka Kurti: What made you interested in writing about the history of Chicago’s Black street gangs?

Lance Williams: I grew up during the civil rights movement and Black Power era. My father was a member of one of Chicago’s first Black Street organizations called the Vice Lords. He was a gang banger and a Black nationalist who believed in Black Power. This was a dynamic combination that I was exposed to in my formative years, and one that left an impression on me for the rest of my life. It shaped my interests in politics, especially how policies have affected the most marginalized and vulnerable people in the Black community. I’ve always been fascinated by the involvement of street gangs and their involvement in social justice movements and local electoral politics. The book attempts to chronicle some of this during early years of the Black Disciples.

In his younger years, my dad did some time in juvenile detention at the Illinois Youth Center – St. Charles. That’s where he and some of his buddies started the Vice Lords. He was in and out of juvie, but in his late teens and early 20s, he ended up getting a job working for the post office, and afterwards as a gang outreach worker. This was the 1960s, at a time when the government was investing money into urban renewal. So, social service agencies like the YMCA started these new initiatives to address the emerging gang problem in cities like Chicago by employing individuals who were reformed gang members, kind of like the outreach workers of today. My father was one of those outreach workers. So, growing up in the summertime, I used to hang out with him as he worked with street gangs around the city. That’s how I got introduced to the streets. I wasn’t a street kid growing up because both of my parents had stable jobs. My mom was a teacher. I always say I was not raised in the streets but raised by the streets.

I always say I was not raised in the streets but raised by the streets.

So fast forward, after being away for college, I came back home to Chicago, and I got a job as a public school teacher. Many of my students were gang affiliated, and they took to me because I understood the culture, where they were coming from, and I was able to speak their language and be sensitive to the kind of ways that they operated. So, we ended up interacting a lot with each other. The school administration saw this and gave me special assignments to work with the boys who were gang affiliated. This gave me the ability to work with them, to expand this work to regional schools, and I gained a reputation for being effective. At that point I decided to get some academic credentials to back up the community work I was doing. I went back to get a master’s degree here at the Center for Inner City Studies, and then I went on to do a doctorate in public health with a focus on gang intervention and violence as a public health issue. That’s how I got into the academy. Because that was a population that I had access to, a lot of my early research involved that community.

I also felt that no one had really captured the history of the streets in a contemporary way, and I wanted to contribute to that. That’s when I hooked up with Natalie Moore, who was a journalist writing about some of the same stuff as me. Together, we wrote the book on the Stones, and now I wrote this book on Mayor Richard Daley and the leader of the Black Disciples, “King” David Barksdale.

While Daley and Barksdale never met, they were both from the South Side. They were tough guys who grew up in rough neighborhoods, one Irish and one Black, and in many ways represented the color line that emerged and was being reinforced in Chicago through the course of the 20th century. Daley and his administration pushed many of the policies that would go on to affect young Black men like Barksdale. Can you tell us about these two powerful figures and the story you wanted to tell?

I wanted to document the early history of African American migration to Chicago, experiences with racial segregation and the impact of the civil rights and Black Power movements from the perspective of the streets. A lot of what we know about the Black community comes from the perspective of middle- or working-class Black folks, and rarely do we hear from the street folks. So I like to include their perspective and experiences in my writing as much as possible.

When you talk to everyday people in the Black community, no other topic sparks such intense engagement and conversation like this history. I realized this when I worked with young people, especially those who were street affiliated. If I wanted to get their attention, I would speak to them about the history of the city and the role the street gangs have played. I could hear a pin drop, that is how engaged they were. So, I always knew that this would be a powerful narrative, but initially I was torn about how to approach it. I had different ideas. But I decided to take one aspect of the street organization and connect it to the larger historical narrative of Chicago in the 20th century. The Daley piece is a part of this history. You cannot tell the history of Chicago at this time without talking about Daley.

In the Black community, people talk a lot about the racial divide in Chicago, and how Black people have been the target of the Irish community’s racism and how Daley as representative of that community and as the mayor of Chicago did everything possible to keep racial segregation intact. I wanted to capture this history from the perspective of those who experienced it and supplement it with interviews, in-depth archival research, and other sources and historical documents. Since Moore and I did the Stones book, it felt only natural to do a book on their rivals, the Disciples.

Barksdale as the leader of the Disciples represented the stories of migration and the impact that segregation had on Black Chicagoans. Barksdale was the son of the South, and his life and that of young people of his generation was deeply impacted by policies that reinforced racial segregation. He ends up becoming the leader of perhaps one of the largest street gangs in the United States. His name continues to resonate today in Black youth popular culture. For instance, in drill music his name frequently comes up, on King David, on BD — his legacy continues to be recognized by Black youth today.

Your book has rich descriptions of what life was like for young Black men like David Barksdale in South Side Chicago in the late 1950s. Can you tell us a little bit about the structural and institutional conditions that Black youth of this generation were facing and why they formed street gangs?

A lot of these stories I got from individuals who were those young Black men and who are still alive today. The number one thing they talk about is how poor they were and how difficult it was for them and their families to survive. Many of them lived in single female-headed households where the mom always worked domestic jobs. At that time, there was no formal structure in place to ensure that a young person went to school. No one was going to come to look for you to force you to go to school. Your mom was at work. So ultimately, what happened is that you were just buying time until you got a little older and could get a job in a warehouse or factory or some kind of manual labor job.

It is also hard for people today to imagine what neighborhoods like Bronzeville, Englewood and Woodlawn looked like back then. Today, there’s about 20,000 people living in Englewood whereas back in the 1960s, there were about 100,000 African Americans living there. Young Black men were living in massively congested urban and industrial neighborhoods, with dilapidated tenement housing, no structural sanitation system or functioning educational systems and social services. As a young man you were just out there among others fending for yourself. So, Black boys started forming groups to protect themselves from other groups of boys in their neighborhood but also from white ethnics who saw them as a threat.

It’s important to note that the groups that formed Chicago’s Black street gangs were the result of older Black street organizations. From the early 1900s to 1940s, there was an underground economy called policy or gambling. The men that controlled it were called policy kings, and they were basically street guys. When prohibition ended, the Italians who were now left without an underground economy to profit from started to encroach on the territory of the Black policy kings. A war broke out between them, and a lot of the Black policy kings were killed. So younger Black men who are coming up at this time had no guidance from older street guys, and that’s where the new crop of Black street gangs comes from. This is a pattern that we will see repeated over and over again. But once restrictive covenants ended in the late 1940s and with policies like urban renewal, Black people were being pushed into Englewood and Woodlawn. These are new spaces that must be settled, and there’s a lot of violence and crime that goes into that.

Have you received any pushback on this point by readers? In the book, you are very critical of Black leadership, especially of Martin Luther King Jr.

The civil rights movement lost that support from the streets because the streets felt like time after time they were being used and then abandoned.

This is just the way things work in terms of the psychology of communities and groups. People generally don’t say anything about something that they agree with but are more likely to comment about stuff that they don’t agree with, or things that make them uncomfortable. The critiques have to do with complaints about how I attacked Black leadership, Black elected officials or Black faith leaders. There are those that argue that I made Dr. King look kind of bad, like he sold out. He abandoned the Chicago Freedom Movement prematurely leaving Black folks who joined his movement, especially the street gangs. But I don’t think it was intentional. He didn’t understand the culture of the streets. He was from down South. He didn’t understand that once you enter a relationship it is important to maintain that relationship at all costs. You can’t just come in and mobilize people, then jump out and leave them. The next time you do that the result will be that when someone comes from that class with that same initiative, then they don’t want to participate. That’s ultimately what happened. The civil rights movement lost that support from the streets because the streets felt like time after time they were being used and then abandoned.

I think it’s important to raise these in-house contradictions. Some people feel that we shouldn’t talk about these in the open and publicly. But historically, some Black leaders have exploited Black people. We can’t just blame the Irish for being racist. For instance, how do we interpret The Chicago Defender newspaper persuading Black people to move to Chicago to take low-wage jobs? Well, they were a PR arm for the Republican Party and the Republican mayor at the time, William “Big Bill” Thompson.

How have the Black Stones and Disciples responded to the books you have written about them?

I really want my work to reflect the voice of the streets, and I want it to be their story to the greatest extent possible. Sometimes I have been criticized for not including the voice of certain individuals in the books I have written. But you can’t talk to everyone, and if I didn’t have any archival sources to back up an individual’s story or perspective, I just didn’t include it.

I also learned a lot from the first book. I got a lot of visits from guys about the first book Natalie Moore and I wrote on the Stones. And because of how street culture works, I was the one approached, not Natalie. What helped was that whether they agreed or disagreed with what was written, they saw that I was trying to be sincere. I am not trying to take advantage of the story or exploit the narrative; I am just trying to tell the best story possible. It also helped that I knew to reach out to people in strategic leadership positions in the organization to let them know beforehand that we were writing the book. That is important because one of the things that comes out when you write books on street organizations is: well, who authorized you to do this? Who gave you the permission to write this book? And of course, I don’t need permission. But out of respect for the culture, I understood the importance of that. And that came from my upbringing. So, I knew before I wrote the book on the Stones that I needed to chat with leadership and tell them I was interested in writing a book, and I negotiated that before I went into the full pursuit of the book. Now for academics, this doesn’t really matter. But if you live in the community, work in the community and your reputation is based on your relationship with folks in the community, this is important to do.

In your book, you engage quite seriously with the extent that Daley and his administration were threatened by the politicization of street organizations like the Disciples. Can you talk a bit about the Chicago Police Department Gang Intelligence Unit and its work?

As I discuss in the book, Dr. King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) got Chicago Black street gangs involved as activists in the Chicago Freedom Movement’s fight for opening housing. This brought the gangs in direct conflict with Mayor Daley who was fighting to maintain housing and school segregation in the city. Running parallel to the gang’s involvement with the Chicago Freedom Movement was their fight for jobs in the construction industry and building trades. Chicago’s three major Black street gangs, the Vice Lords, Blackstone Rangers and Disciples formed a group called LSD that stood for the Lords, Stones and Disciples. LSD had brought Chicago’s entire building industry to a screeching halt amassing as many as 1,000 gang member protesters to shut down construction sites around the city that refused to hire Black people. Their closures had caused $80 million in losses.

When Daley saw this, he knew he had to do something to stop Chicago’s Black street gangs in their tracks. So, once the mayor was successful in derailing the Chicago Freedom Movement and chasing Dr. King and SCLC out of town, he immediately set up a new Gang Intelligence Unit (GIU) within the Chicago Police Department to go after the gangs. The first thing the GIU did was to build a dossier of David Barksdale and other gang leaders. Their daily activities were monitored: residences, cars they drove, businesses they patronized, organizations they frequented, and the names, addresses and phone numbers of their friends, family and gang associates. Then, the mayor had GIU trump up charges on the leaders of LSD. Bobby Gore, a Vice Lord and Leonard Sengali, a Blackstone Ranger, were both charged with bogus murders. Barksdale escaped the charges because he never played a prominent public role in LSD. He sent Disciples to the protest, but Barksdale wasn’t one to do a lot of public speaking like Gore and Sengali.

It seems like there is a general apathy among young people today and mistrust of leadership very similar to the era you cover in your book. How do you think this history and mistrust of Black leadership has impacted the present moment? Three years ago, the U.S. witnessed the largest uprising since the 1960s sparked by the murder of George Floyd and a global health crisis. You have your ears to the streets, what were people saying about Black Lives Matter?

The problem we have with violence today is that there is nothing to galvanize youth like there was during the 1960s. The Black Lives Matter (BLM) organizations did not engage with youth from the streets. The BLM movement itself came because of people who were directly being affected by police violence, but it was not led by them. People from the streets saw this, and they did not feel that the movement was for them. I talked to guys that are still active in the streets. We had the opportunity to analyze and discuss it. A lot of things were happening at once because of COVID-19 as well. There was stress about COVID. People were stuck at home with people coming home from jail, worrying about catching the virus. People were being released from jail without any support or resources. The police withdrew from doing their jobs, and the way the streets looked at it was like, ‘Well now I can really do my thing out here.’ And then there are protests in the streets. A lot of street guys felt that, ‘Hey if looting happens, yeah, I will go.’ But otherwise, they don’t trust the BLM leadership. They felt it was flimsy, and they would be put in dangerous situations that could get you killed.

Thinking about the current moment and all the talk of violence in Chicago, what are politicians and elites getting wrong?

I would say that since the early 2000s to the last year or two, much of what has happened in the streets as it relates to violence is not related to gangs. The gang has not gone away, but the violence is not related to gangs. People are getting into it because of interpersonal stuff, not because of gang affiliation. Stress is impacting people on an individual level and makes it interpersonal. But now, so much of the interpersonal has impacted the group, it’s become so pervasive, it’s organizing the small groups again, and it’s moving us to a new era of gang banging. We’ve seen this over the years where, you get peaks of gang activity. It’s always forces outside of the community that spark gang violence, whether its heroin or some ridiculous new policy like Renaissance 2010. The interpersonal stuff has caused groups to form and defend themselves to retaliate for their losses. I am seeing more references to “I am a Black Disciple,” “I am a Gangster Disciple.” For the last 20 years this identification or expression was not an issue because the infrastructure of the organization is done. It is now turning to a popular culture thing where drill musicians are identifying with it.

You mentioned Renaissance 2010 as a policy that has exacerbated youth violence. Can you say more?

This was in the early 2000s and at the time, Arne Duncan was the CEO of Chicago Public Schools. Basically, in the name of improving neighborhood public schools, Renaissance 2010 basically privatized them through the creation of charter schools. What happened is that the schools they labeled as dysfunctional were in the poorest neighborhood that had the highest level of gang affiliation. So, when you turn those schools into charter schools, they come up with their own criteria for admission. What happened is that these neighborhood high schools in these areas that had strong gang traditions closed down. If you are a regular kid, you probably don’t have a problem because that is not your life. But if you’re active in the streets, you have a problem now, because you can’t go too far from the neighborhood. Once you start moving out of your neighborhood, you are going to be confronting your rivals at every turn.

Which was the same thing that happened historically on the South Side with urban renewal.

Now a young person must cross rival territories to go to high school. But instead of doing something so dangerous, he chooses to not go to school.

In the book, I discuss how urban renewal policies led to the rezoning of Hyde Park Academy High School which caused the initial beef between the Stones and Disciples. The same thing happens again, but now it’s not just one neighborhood, it’s pervasive throughout Chicago. Now a young person must cross rival territories to go to high school. But instead of doing something so dangerous, he chooses to not go to school. So, for the past 20 years he’s been on the block. Back in the day he would have been able to make some money from the cocaine economy, but now that is gone. He is just languishing in the neighborhood. He’s got a little access to weed, alcohol and pills and is self-medicating from the trauma. Now any little thing that pops off gets him. He’s agitated and has easy access to guns, and the violence occurs. This has been brewing for 20 years to the point that everybody has lost somebody to the point that nobody is really trying to hear anything. That one policy contributed to mass killings in the Black community.

The city knows it contributes to the problem with Renaissance 2010, and it’s clearly costing the city money, but they don’t want to invest the money to fix it. Ultimately, they don’t want to give billions of dollars to poor Black and Brown people or invest in resources to fix the root causes of the violence.

In my own research in the South Bronx in NYC, I spent a lot of time with organizations that were spearheading violence prevention initiatives. They hired formerly incarcerated guys who could relate to young people and persuade them to leave the gangs they were part of. But the jobs are all mostly part time, and there seems to be very little resources actually dedicated to preventing violence and to help gang affiliated youth find other alternatives.

They give you no resources to engage the guys. You come in and tell them war stories about how you messed up the community, and they shouldn’t do the same thing. But guess what, the guys are still stuck, and because of the music they think the violence is sexy, and you are an old timer with no solutions, so they don’t want to hear it. But if you took that same organization and invested a ton of money and paid everyone because they are risking a lot, including the guys you are trying to help, it would work. The city has the money but not for the street-involved Black men. In the book, I talked about the job training programs. They work, but the city must put money and resources into them.

Right now, in Chicago, Arne Duncan, the same guy whose policy Renaissance 2010 fueled the violence, has founded Chicago CRED, an organization dedicated to reducing gun violence. He set the communities on fire and now he gets to come and get the city’s money to put the fire out. Unlike ex-offenders who work in his organization who have had to atone for the past damage they have caused the community, he has never, to my knowledge, publicly apologized for the destruction that he personally heaped on the Black community. In fact, after he destroyed Chicago’s public schools, he went on to be secretary of education under Barack Obama. These are the kinds of politics we should be critical of. This is why I wrote this book. Daley and Barksdale are the symbols for the undercurrents that we need to confront like institutional racism, misguided public policies and classism.