Support justice-driven, accurate and transparent news — make a quick donation to Truthout today!

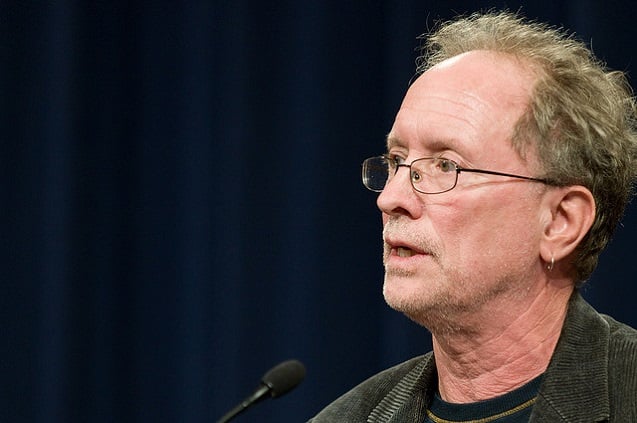

Jerome Phillips / Flickr)” width=”637″ height=”423″ />Bill Ayers. (Photo: Jerome Phillips / Flickr)

Jerome Phillips / Flickr)” width=”637″ height=”423″ />Bill Ayers. (Photo: Jerome Phillips / Flickr)

Upon the release of Bill Ayers’ new memoir, Public Enemy: Confessions of an American Dissident, I attended his reading in an assembly hall in Hyde Park, Chicago, not far from the homes of both Ayers and Barack Obama. As soon as the Q&A segment was declared, a well-groomed, loud-voiced person who clearly had been preparing his question for quite some time inquired grandly, “Do you think a violent, right-wing radical could’ve become a professor and successful scholar, like you did as a left-wing Weather Underground radical? Could that happen?”

After a few “minor” corrections from Ayers, who is indeed a renowned education scholar – “just to clarify, we didn’t actually injure any people” – Bernardine Dohrn, an accomplished law professor as well as Ayers’ former Weather Underground comrade and current wife, stepped up to the mic.

“The academy is filled with right-wing people who’ve committed massive acts of violence,” Dohrn said, calmly. She went on to explain that many academics have killed vast numbers of people in foreign wars, some directly through the military, some through designing the weapons that make those acts of killing possible. Professors have designed interrogation programs, overseen torture, strategized murderous attacks and mounted tragic wars. Dohrn concluded, “It happens all the time.”

Ayers’ and Dohrn’s responses were elegant – and, perhaps, readied; they’d no doubt heard this question before. Public Enemy chronicles the explosion of scorching personal attacks on Ayers during Obama’s first campaign for the presidency, when the then-candidate was accused of “palling around with terrorists,” i.e. Ayers and friends. The memoir also reaches back to similar past eruptions of vicious publicity, tracing the construction of Ayers as a “cartoon character,” the product of “a kind of weird political cage fighting, a bloody performance art.”

The use of “bloody” isn’t exclusively metaphorical; Ayers received a slew of violent hate mail, including threats of waterboarding and dismemberment. He became the narrow, embodied target for the unbridled wrath of large numbers of Americans struggling with their anger at politics, government, culture, themselves.

The cartoon character quickly solidified and gained a clearer shape. Ayers writes: “An endlessly repeating epithet had begun to sound – even to me – like a natural part of my given name. ‘Unrepentant Domestic Terrorist William Ayers.’ Who would name their child Unrepentant? And even worse, who would call their kid Unrepentant Ayers, with three middle names?”

Later, in a segment on progressive education, Ayers highlights the importance of recognizing all humans as varied, vast and contradictory, to enable both a good educational system and and a good society. “The democratic injunction insist[s] that every person was an entire universe,” he writes.

The message: No self can be squished into an awkwardly constructed epithet. However, in the case of Unrepentant Ayers, profit and politics displaced the democratic injunction. Ayers-related rumors sold – they were tabloid fodder for the corporate media’s stupification fetish, fanning the myths about Obama’s secret Muslim (a k a “terrorist”) identity and radical leftist (a k a “terrorist”) roots. They were a dependable hit.

Most of the education-related speaking gigs Ayers had lined up for the next month were canceled by their host institutions, each cancellation accompanied by an uncreative excuse. In eliminating the “public enemy” from their midst, these universities neatly set aside their free-speech-oriented ideals. (A similar flurry of cancellations had occurred more than a decade ago, when Ayers’ previous memoir, Fugitive Days, was released – the day before September 11, 2001!)

The author’s point is not that he hasn’t gotten as many opportunities to speak publicly as he’d like. Instead, he’s looking at the ways in which certain types of speech – profitable ones and electorally beneficial ones, qualities that are, of course, interrelated – are elevated and amplified, while others – voices of dissent and political creativity – are quashed.

Vocal, participatory engagement with ideas is central to the vision of a just world articulated throughout the memoir. For example, Ayers sees book readings as an “excuse “to assemble in a public space in order to conduct the business of democracy.” But a profit-driven system hungers for the cartoon characters and the bloody acts of performance art, the political cage fights and the emblazoned epithets, each of them commodities to be sold and consumed.

In this way, Public Enemy’s presence as a memoir is itself an act of democracy. It tells the story of a complex life, the opposite of an awkward epithet, and in doing so imparts striking insights about the nature of the self and its place in society.

At one point, Ayers receives a piece of hate mail that announces, “You know exactly what you are and you know Obama as well as anyone, you lying fucker.”

“Actually,” Ayers responds merrily, “I don’t know who or what I am, in part because my self-awareness is as blurry as anyone’s, and beyond that I embody a mass of contradictions that I’m in no hurry to resolve – so I’ll just have to remain ambiguous, undecipherable, and suspended in the middle of things, just like everybody else.”

Embracing this spirit of ambiguity and multifaceted-ness, Ayers devotes a significant portion of Public Enemy to a time long before Barack Obama hit the halls of the Senate. He recounts his children’s early years, the ways in which the political bumped up against and merged with the personal in the process of wandering along with them as they grew. A series of penetrating vignettes unfolds: The kids’ soul-transforming day care teacher inspires Ayers to pursue a career in education, Dohrn creates a mountain of intricate chapter books for the kids while she’s incarcerated for her refusal to testify before a grand jury, Ayers and Dohrn adopt the child of two incarcerated friends and fellow activists, the day care kids triumphantly deliver two giant heart-covered carrot cakes to a group of ministers on a hunger strike. Each vignette is charged with political significance, but it’s not always outright. The children, Ayers and Dohrn are painted as whole and complicated: fallible, hilarious, sad, joyful, human. In an era of media caricature-pushing, putting forth such real characters seems itself an act of rebellion, especially flowing from the pen of the Unrepentant Domestic Terrorist himself.

A memoir like this easily could descend into self-righteousness or self-aggrandizement. Instead, Ayers makes humility a central tenet of his exploration of selfhood.

“No one can ever write the real story of a life,” he notes. “The real story is the story of life’s humiliations.”

Consequently, and refreshingly, Ayers chronicles his mistakes and embarrassments with vigor. One of the book’s most remarkable interludes encompasses his internal response to incessant requests that he issue an apology: He compiles a list of things he might be expected to apologize for. Highlights include: “destroying draft board files”; “laughing out loud in church”; “my manner”; “driving too fast and rarely getting a speeding ticket”; “being born”; “exaggerated claims and inflated rhetoric”; “talking too much”; “disabling B-52s headed for Viet Nam”; “being way too happy; doing anarchist calisthenics at odd times and in inappropriate venues; oh, and yes, there’s the matter of vandalism and destruction of property, including a series of high-profile bombings of government and corporate buildings, each a symbol of war and empire, oppression and white supremacy, each accompanied by an explanatory if rhetorically overheated statement or communiqué. And if that’s not enough, there’s the fact that I was born in the suburbs.”

In his assessment of humans as multidimensional universes, Ayers doesn’t limit his focus to radicals, progressives and toddlers. At one point in the thick of the 2008 torrent of threats and attacks, Ayers enters into a friendly conversation about state-sanctioned marriage with a Ron Paul supporter picketing one of his speeches. Later on, he and Dohrn host a dinner at their home for Andrew Breitbart, Tucker Carlson and friends and have a delightful time of it. They don’t avoid politics – the table conversation is irreverently heated and “utterly surreal” – but there’s also laughter. And at the end of the night, each guest receives a swag bag filled with candy kisses and one of Ayers’ books. He signs Carlson’s: “To my new best friend!” Soon after, Breitbart tweets that Ayers and Dohrn were “charming,” and announces a desire to embark on a cross-country road trip with Ayers.

In the end, Public Enemy seems to be asking us, what’s the point of politics? Is it about celebrities? The manipulation of a cast of characters, both good and evil? (The “hero” Obama, the “terrorist” Ayers?) The book suggests that these faces are distractions. Effective politics is about working toward systemic change and confronting oppressive systems. Public Enemy also points to new possibilities for a politics grounded in the small transformations that spark up in communities every day. Transformative teaching can be an act of social justice, of revolutionary politics. So can parenting. So can love. (Think heart-shaped carrot cakes for hunger strikers.) Character assassination, however, cannot.

Public Enemy, in fact, does away with the concept of a “public enemy,” denying the power of such labels to mete out justice – or, even, to communicate. During the course of discussing his hypothetical “apology” for his acts committed during the struggles for civil rights and peace, Ayers imagines a potential path to real justice: a truth and reconciliation commission, in which the horrors of the Vietnam War and civil rights struggles are revealed and reckoned with. In such a commission, each of the war’s leaders and major actors would descend a spiral staircase onto a stylishly lit stage (Ayers suggests the Kennedy Center or Kodak Theater), and announce to the world their “failures to act with integrity, transgressions and offenses, stupid statements and malevolent acts, wrongdoings and misconduct, gaps and omissions and avoidances.” Then, victims – Vietnamese villagers and the families of assassinated civil rights leaders, among others – would be invited to tell their stories. Discussion of “why”s and “how”s would ensue, and “society would have the opportunity to witness all of it to understand the extent and depth of the disaster as a step toward putting it behind us and moving forward.”

If the real story of a life is the story of its humiliations, then perhaps the same is true for the story of a country. Ayers’ proposal of a truth and reconciliation commission points to the prospect of a sort of national memoir, a memoir that would paint an intricate and humiliating picture of the forces that have driven the tragedies of our past. Public Enemy demonstrates the potential of memoir to infuse politics with humanity, conflict with compassion, backlash with love. It is a soul-excavating labor that opens the democratic vista beyond the dead end of caricature formation and the suppression of dissident voices.

A terrifying moment. We appeal for your support.

In the last weeks, we have witnessed an authoritarian assault on communities in Minnesota and across the nation.

The need for truthful, grassroots reporting is urgent at this cataclysmic historical moment. Yet, Trump-aligned billionaires and other allies have taken over many legacy media outlets — the culmination of a decades-long campaign to place control of the narrative into the hands of the political right.

We refuse to let Trump’s blatant propaganda machine go unchecked. Untethered to corporate ownership or advertisers, Truthout remains fearless in our reporting and our determination to use journalism as a tool for justice.

But we need your help just to fund our basic expenses. Over 80 percent of Truthout’s funding comes from small individual donations from our community of readers, and over a third of our total budget is supported by recurring monthly donors.

Truthout’s fundraiser ended last night, and we fell just short of our goal. But your support still matters immensely. Whether you can make a small monthly donation or a larger one-time gift, Truthout only works with your help.